Art about Working People

The earliest ideas about a day to honor working Americans came about from labor unions in the 1880s. In fact, the idea of a national holiday is thought to have come from labor union officials in New York. Before Labor Day was a federal holiday, it was recognized by labor activists and some states. Many states in the 1880s passed state laws recognizing Labor Day, but it was not enshrined as a national federal holiday until President Grover Cleveland (1837–1908) signed the legislation in 1894. The first ever celebrated Labor Day was in New York on 5 September 1882. Throughout art history, art has documented and celebrated working people all over the world.

|

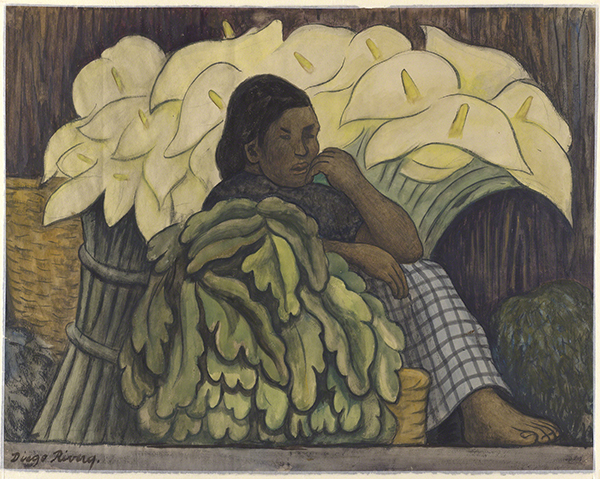

| Diego Rivera (1886–1957, Mexico), The Lily Vendor, 1935. Charcoal and watercolor on paper, 19 1/8" x 24 ¼" (48.6 x 61.6 cm). Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. © 2023 Banco di Mexico Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museum Trusts / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (PMA-9294) |

When Diego Rivera returned to Mexico in 1921 from his studies in Europe, he was struck by how much of his country's indigenous culture aroused ideas for subject matter. He therefore rejected any European traditions of subject matter—be they historical, religious or philosophical—for those that corresponded to what he saw on a daily basis in Mexico. Calla lily vendors are the subject of countless works by Rivera and appear in many of his murals.

The calla lily symbolizes the rich tropical environment of Mexico in Rivera’s art. He repeatedly contrasted the beauty of the flower with a flower seller, depicted as a poor working person. A symbol of rebirth and resurrection because of the use of lilies in funerals, Rivera was also subtly emphasizing that the Mexican people should rise and form a reborn nation after the Mexican Revolution (1910–1917). The format of this drawing, seen from a lower vantage point, may indicate it was a study for a section of a mural.

Rivera was one of the great painters in the 1900s and a pioneer of the Mexican Mural Movement. His paintings, particularly his murals, have influenced mural painting in the United States from the Social Realism of Depression-period murals to the civil and women’s rights murals of the 1970s and early twenty-first century. The influence has been both stylistic and subject oriented. Rivera is also well-known as the husband of Mexican Surrealist painter Frida Kahlo (1910–1953).

After studying at the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City, Rivera spent ten years (1910–1920)—the years coinciding with the Mexican Revolution—in Europe. He studied great masters in Spanish museums and became acquainted with Cubism while in Paris. He also developed an abiding connection to Renaissance and Baroque frescoes in Italy.

His mature style, for which Rivera is best known today, is a combination of the classical fresco techniques he learned in Italy and various cultural references. It is characterized by solidly modeled forms, the influence of both Giotto and Mayan sculpture, the shallow frieze-like space seen in ancient Mexican manuscript painting, and decorative motifs seen in both Mesoamerican relief carving and pottery decoration.

|

| Isabel Bishop (1902–1988, U.S.), Lunch Counter, ca. 1940. Oil and tempera on Masonite, 23" x 14" (58.4 x 35.8 cm). Courtesy of the Phillips Collection, Washington, DC. © 2023 Artist or Estate of Artist. (PC-482) |

In this shimmering painting, two office workers appear together outdoors and in a shallow, undefined setting typical of Isabel Bishop’s work. Stylistically, these works combine the artist's respect for traditions of modeling and composition with the modernist practice of redefining the traditional depiction of space. Bishop’s composition emphasizes its two-dimensional nature. The volumetrically conceived figures are arranged against a filmy grid of thick repeating horizontals, setting off the vertical pose of the two women.

Bishop’s most recognizable and numerous images are those of working women from the 1930s, a period when more women needed to get out and work. Lunch Counter dates from a period when she began making prints to be made readily available to the general public. The two figures stand in a classic contrapposto (weight shift) pose, a motif straight from ancient Greece and monumentalized during the Renaissance. In her use of white pigment in highlights, Bishop’s work reflects a similar visual effect to works by El Greco.

Although the scene in no way possesses a “feminist” point of view, Bishop’s careful attention to defining the figures in a light-filled space gives the women dignity and monumentality. Bishop’s figures are set against a fairly empty background, further focusing attention on them. Her empathy for the subject is readily apparent in the sensitive portrayal of modest city dwellers. The fact that these women are anonymous elevates the subject to a somewhat iconic depiction of the modern American woman of the day.

Born in Cincinnati and raised in the Midwest, Bishop moved to New York right after high school in order to study painting at the Art Students League in 1920. While studying there, Bishop developed a strong interest in the nude and figurative art. Her mentor at the league was Kenneth Hayes Miller (1876–1952). Miller was an urban realist who believed that contemporary realism should have the same strong plastic values and structure as Renaissance painting. Although Bishop also admired Baroque and Renaissance painting, her brand of realism developed in a less mannered fashion than Miller. She did strive to incorporate traditional Renaissance concepts of space and balance in her works.

Bishop consciously avoided any sort of social commentary or criticism in her work. She was concerned with capturing impressions of movement and confined her subject matter to the people she saw near her 14th Street studio in New York, in the subway, and other public places. If a particular pose caught her eye, she often asked people she met on the street to model in her studio.

|

| Consuelo Kanaga (1894–1978, U.S.), Untitled (Workers in Tennessee), from the Tennessee Series, 1950. Gelatin silver print on paper, 6 7/8" x 8 ¼" (17.5 x 21 cm). Courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum. © 2023 Artist or Estate of Artist. (BMA-1398) |

The 1949 Museum of Modern Art, New York, exhibition 50 Photographs by 50 Photographers: Landmarks in Photographic History included the work of documentary photographer Consuelo Kanaga. The following year, Kanaga began to document African American migrant workers in the South. She approached her documentary subjects as individuals while avoiding sensationalized or overly emotional compositions. The documentation of African American farm workers in the South was one of Kanaga’s biggest undertakings. It was initiated at a time when it was unusual, if not unheard of, for white photographers to create monumental images and sensitive portraits of Black people.

Kanaga's documentary photos reveal a careful composition that borders on posing, although she took multiple exposures and chose the one she felt best represented her feelings at the time. In her farmworker series, she tended to isolate figures she felt held a powerful message against a negative space, like the sky. This not only focuses the message of the image, but also lends the subject a gravity and dignity that was totally the artist’s intent. The choice of a "worm's eye view" also lends monumentality to the image of the laborers in Untitled (Workers in Tennessee).

Like Dorothea Lange (1895–1965), Berenice Abbott (1898–1991), and Margaret Bourke-White (1904–1971), Kanaga was an important documentary photographer in the middle of the 1900s. Her political and social ideologies guided her art. At a time when most social commentary in photography involved images meant to shock the viewer into action, Kanaga’s images seduced the viewer with careful composition, intuitive cropping, and reframing.

Born in Oregon in 1894, Kanaga first began taking pictures in 1918 as a staff photographer for the San Francisco Chronicle. Though self-taught, she became a master printer, quickly absorbing the innovations of the Photo-Secession. This group espoused the principles of Pictorialism, which held that what was significant about a photograph was not what was in front of the camera, but the manipulation of the image by the artist/photographer to achieve his or her subjective vision.

As a newspaper photographer in California and later as a documentary photographer in New York in the early 1920s, Kanaga recorded rural and urban poverty, displaced children and mothers, and labor unrest. She was an active member of the socially committed Photo League and published many of her images in such radical periodicals as New Masses, Daily Worker, and Labor Defender. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, Kanaga traveled throughout the South recording the lives of Black migrant workers.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art 2E Grade 2: 5.6, 5.7., 5.8, 5.9; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 5: 1.8; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 6: 1.4; Experience Art: 2.1; A Community Connection 2E: 2.1; A Global Pursuit 2E: 5.1, 5.5; A Personal Journey 2E: 2.1

Comments