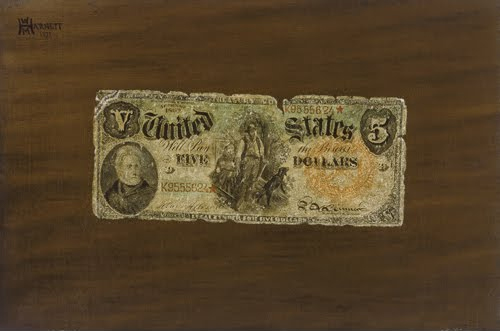

Art Breaking the Law? William Michael Harnett

Having said last week that I’m “not a big fan of realism,” I’ll punish that thought again by showing you a work by a master realist. I just came across this work in passing, and it reminded me of an interesting story about this particular painting and the artist who painted it.

|

| William Michael Harnett (1848–1892, United States), Still Life—Five Dollar Bill, 1877. Oil on canvas, 7 7/8" x 12 ¼" (20 x 31 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-2804) |

If you’re thinking that an artist could never been arrested for his work, then let’s think back to the Baroque period when Caravaggio was condemned by the Roman church for “blasphemy,” and when Daumier was thrown in prison for “insulting” the French king Louis Philippe, not to mention Hitler’s complete shutdown of the Bauhaus artists as “degenerate.” I do like the paintings of William Harnett for his technical mastery, but this has to be one of my favorites just because of the story that goes with it.

I’ve discussed the American preoccupation with realism in previous posts. Among the other styles explored in America during the late 1800s, trompe l’oeil (fool the eye) realism represented the survival of a strain in American art dear to Americans. Its precedents include Flemish and Dutch Baroque still life, and closer in time, the work of Charles Willson Peale, especially his Staircase Group, to which George Washington allegedly once tipped his hat. I have always thought that trompe l’oeil realism by Harnett and others was a reaction to the increasing popularity of photography at the time.

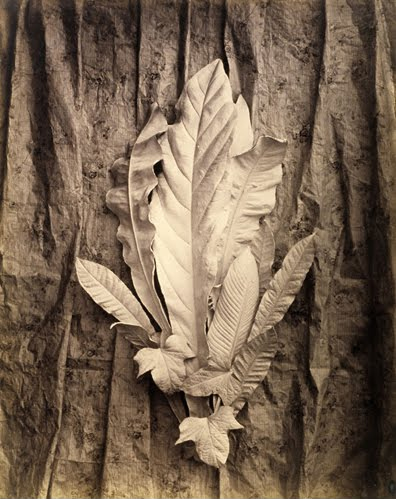

Harnett was trained in painting at the National Academy in New York. He went to Europe in 1880, first to London, then to Frankfurt and Munich, at the time the home of a large group of expatriate American artists who painted in the painterly Dark Impressionism style influenced by Dutch and Spanish Baroque. Harnett instead preferred super realism, primarily still life since he was too poor to afford models. His still life paintings recall the work of then-contemporary French photographer Charles Aubry, whose work he probably saw.

|

| Charles Aubry (1811–1877, France), Still Life—Leaves, ca. 1864. Albumen print, 18 7/8" x 1 1/8" (48 x 38 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-2478) |

While Harnett is most famous for his hunting accoutrements on the back of a door, and small still life of various newspapers, he introduced a new subject: money—not just money as part of a larger still life, but as the single focus. Here’s where the “crime” comes in. In 1877, he produced this painting, which was hung in a saloon in New York. In the nineteenth century in America, counterfeiting currency was a big problem. It is estimated that by the time of the Civil War (1860–1865), a third of paper money in circulation in the US was counterfeit. Thus, authorities were wary of anyone who could so expertly reproduce money as an art subject. This painting was confiscated and Harnett arrested. A judge admonished him that such a talent “so capable of mischief: should not be encouraged. Harnett never painted money again.

|

| John Haberle (1856–1933, US), Imitation, 1887. Oil on canvas, 10" x 14" (25.4 x 35.56 cm). © National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. (NGA-P0989) |

Another artist, John Haberle, ignored Harnett’s warnings to “stop painting greenbacks,” and made the subject his specialty.

Correlations to Davis programs:Explorations in Art Grade 2: 5.27, Explorations in Art Grade 4: 6.36; Explorations in Art Grade 5 2.7, 2.8; A Personal Journey: 2.4; Discovering Art History: 12.3.

Comments