Deceiving the Eye: American Trompe-l'Oeil Realism

I’ve written before about the long-standing interest in extreme realism in American painting. Colonial American self-taught artists (“limners”) may not have been schooled in anatomy, but they sure as heck could depict the shimmer of the silk or velvet clothing covering that body.

The Hudson River School artists of the first half of the 1800s believed in the accurate visual description of places in the American wilderness. And the New Realism movement of the 1960s and 1970s was just a spike in the popularity of a genre that continues to captivate.

Shame on me as an art historian for thinking of the Trompe-l’Oeil (Fool the Eye) Realism movement as an 1880s and 1890s phenomenon. The style, influenced greatly by the exquisitely painted realism of Dutch Baroque still life, was dominated by compositions of mundane everyday items presented with a stunning deception, often with images painted to “break the picture plane.” Well, looky what I found—trompe l’oeil realism from our early Republic!

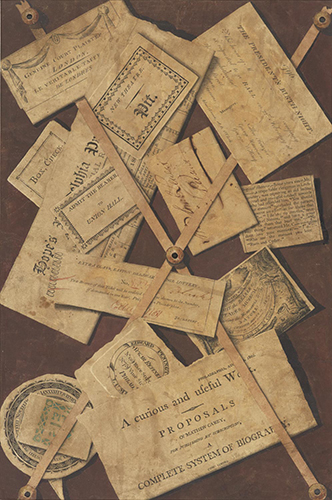

|

| Samuel Lewis (1757–1822, United States), A Deception, ca. 1802. Black and brown inks, matte opaque paint, gold metallic paint, watercolor, graphite and scratching out on wove paper, 16 3/16” x 10 13/16" (41.1 x 27.5 cm). © 2017 Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-8129) |

On May 22, 1795, the first exhibition of the Columbianum—the American Academy of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture—took place in Philadelphia. Although this attempt at an American academy subsequently failed, this show importantly showcased mostly American artists. It included several still-life paintings, which were, at the time, rare in American painting. The exhibit featured the Staircase Group by Charles Willson Peale, as well as a trompe l’oeil still life by a “writing and drawing master” named Samuel Lewis.

Lewis subsequently donated A Deception to Peale’s Philadelphia museum in 1808. I think this painting is a masterpiece in every sense of the criteria of the trompe l’oeil style, which was perfected by artists in the second half of the 1800s. Lewis’s work includes impeccable imitations of printed script on the various pieces of paper, indicating that he was well-versed in contemporary fonts as a writing master.

I found nothing of background information about Samuel Lewis, except for what I found in the book Citizen Spectator by Wendy Bellion (2011, Omohundro Institute of American History and Culture, Williamsburg, VA). This book explores the late-1700s Enlightenment interest in vision and optics as they related to the development of extremely realistic/illusionistic painting. Of course, this interest in optics also ultimately led to the invention of photography.

|

| Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827, United States), Staircase Group (Portrait of Raphaelle Peale and Titian Ramsey Peale), 1795. Oil on canvas, 89 1/2” x 39 3/8" (227.3 x 100 cm). © 2017 Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-532) |

By the time Peale painted this, he had abandoned his lucrative portrait painting business in order to explore his passion for natural sciences and his run personal museum in Philadelphia. Illusionistic realism was already a fad in the US. Peale used this to show that American artists were just as talented and witty as their European counterparts. Indeed, the whole idea behind the Columbianum (located in the Pennsylvania State House) was to afford Americans a homeland alternative to studying in Europe.

American artists drew from a long tradition of illusionistic realism in Western art, including Dutch and Flemish Baroque portraiture and still life. Peale’s Staircase Group itself references a painting by Antonie van Dyck (1599–1641) of Lord John Stuart and His Brother, Lord Bernard Stuart (National Portrait Gallery, London). Peale, however, emphasized the complete negation of the picture plane by including an actual doorframe and wooden step when the work was exhibited at the one and only exhibition at the Columbianum. Apparently, Raphaelle Peale (1774–1825) is said to have witnessed the George Washington (died 1799) tip his hat at this painting when he visited the Peale Museum in 1797.

Here are some Trompe l’Oeil realists you may recognize:

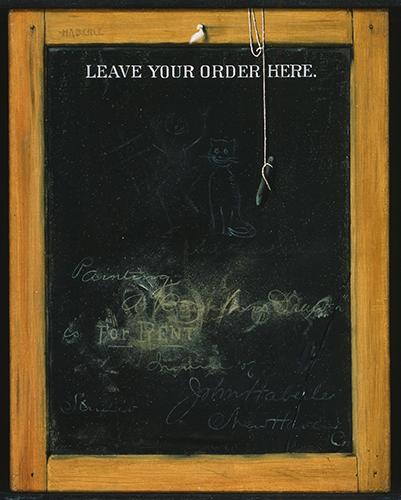

|

| John Haberle (1856–1933, United States), The Slate, ca. 1895. Oil on canvas, 12" x 9 3/8" (30.5 x 23.8 cm). © 2017 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (MFAB-449) |

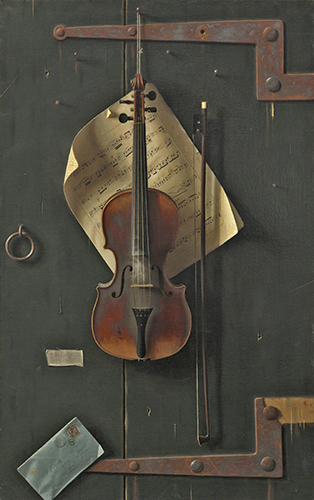

|

| William Harnett (1848–1892 United States, born Ireland), The Old Violin, 1886. Oil on canvas, 38" x 23 5/8" (96.5 x 60 cm). © National Gallery of Art, Washington. (NGA-P0920) |

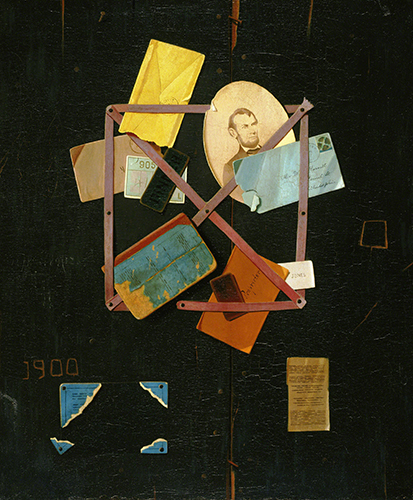

|

| John Frederick Peto (1854–1907, United States), Old Time Card Rack, 1900. Oil on canvas, 30” x 25 ¼" (76.2 x 64.1 cm). © 2017 The Phillips Collection, Washington. (PC-320) |

Correlations to Davis Programs: Discovering Drawing 3; The Visual Experience 9.9

Comments