National Garden Month 2021

It's National Garden Month and National Landscape Architecture Month. But I’ll deal with the landscape gardening later. I just want to show gorgeous art that may be slightly different than what is usually perceived as gardens. And that’s what artists do! These three artists are all inspirations for my personal painting. Look at the luscious swipes of pure color in this Cézanne work!

|

| Paul Cézanne (1839–1906, France), Garden at Les Lauves, ca. 1906. Oil on canvas, 25 ¾" x 31 7/8" (65.4 x 80.9 cm). © 2021 The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC. (PC-48) |

This painting represents an unfinished view of one of the dozens of artworks of Mont Sainte-Victoire that Paul Cézanne created. This work features the garden at his studio in Les Lauves, near Aix-en-Provence in the south of France, in the foreground. Perhaps more than most of his works, it graphically demonstrates his technique of using swatches of cool and warm colors. By limiting the number of colors in his palette, he was able to more easily maintain control over saturation and value within the composition.

Cézanne often expressed admiration for such Renaissance and Baroque artists as Titian, Rembrandt, and Rubens, in that they could get across deep emotion in their works yet maintain a realism faithful to nature. In this late work, the artist's deep reverence for nature is translated into color patches and lines of color both parallel and perpendicular to the horizon line, setting up a series of visually exciting juxtapositions, while still expressing the main idea of landscape.

Born in Aix-en-Provence, from an early age Cézanne developed an interest at art. Although the young Cézanne initially attended law school, in 1856 he began to attend art classes at the School of Fine Arts in Aix. He eventually decided that he wanted to be a painter and moved to Paris in 1861. His father granted him an allowance so he could live independently. After his father’s death he received a large inheritance.

While taking painting classes, Cézanne studied great artists of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, as well as Romanticism, especially the work of Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863). He also gravitated toward more unconventional contemporary painters Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) and Edouard Manet (1832–1883).

The most significant influence on Cézanne’s early work began when he moved to Pontoise and worked with Camille Pissarro (1830–1903), at the time an unrecognized painter living near Paris. Pissarro introduced Cézanne to the impressionist palette and technique of painting outdoors. Cézanne developed a painting style that involved working outdoors rapidly and at reduced scale, using small touches of pure color. He exhibited with the Impressionists in 1874 and 1877.

In the 1880s, Cézanne spent most of his time in Aix. Feeling that Impressionism was too restrictive and formulaic, he resolved to develop a style that embodied the direct observation of nature of Impressionism and the balanced, structured compositions of the Renaissance and Baroque. Because he added underlying structure to the random impressionist technique, Cézanne’s style is called Post-Impressionism.

By the 1890s, Cézanne had developed a technique that he called “constructive.” Based in the basic geometric shapes of the cylinder, cube, and cone, he built his forms up from groupings of parallel, hatched brush strokes, the groupings constituting the mass. Through the 1890s he refined his technique, always maintaining compositional balance and structure, but now infusing his hatched forms with a sense of shifting planes in atmosphere.

Cézanne stabilized the shifting colors of Impressionism into an array of clearly defined planes. Those planes comprised objects and elements of the landscape. What he had created was an approximation of perceived nature bounded by his theories on the underlying forms of nature. By varying the saturation of the colors so little, time of day and light source are difficult to discern. His works took on a vaguely abstract nature by the early 1900s, although he never divorced his works from the object.

|

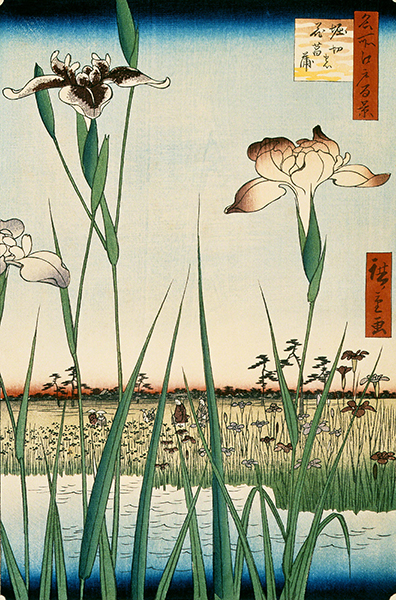

| Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858, Japan), Iris Garden at Hokiri, print #64 from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Color woodcut print on paper, 14 3/16" x 9 7/16" (36 x 24 cm). © 2021 Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-795) |

I can’t resist including my favorite ukiyo-e landscapist, Hiroshige. His instinct for bold composition never fails to amaze me. In this work, Hiroshige demonstrates his brilliance at balance between horizontal and vertical elements in landscape, even in this close up of flowers.

Flower breeding was popular in the late Edo period. The iris—along with azaleas, chrysanthemums, and morning glory—was one of the flowering plants raised to produce more colorful and exotic varieties. Like many of the prints in this late series, the main subject (three of the newest specimens of iris) is in the immediate foreground, with the human presence greatly diminished. The saturated blue at top and bottom are the result of imported Western aniline dyes, the brilliant color of which was appreciated by Hiroshige and incorporated into many of his prints.

Hiroshige was one of the most famous landscape artists of the first half of the 1800s. From childhood, he showed a propensity for art and his father arranged for him to have lessons by an amateur painter. At fifteen he went to train with an Utagawa School artist Toyohiro (1773–1828), a landscape painter, print designer, and illustrator. While under Toyohiro’s tutelage, Hiroshige produced actor prints. His progress was so rapid, that he was admitted into the Utagawa fraternity within a year and given the name Utagawa Hiroshige.

Until 1830, Hiroshige mostly produced prints of kabuki actors and beauties. However, the publication of Katsushika Hokusai’s Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji between 1826 and 1833 showed Hiroshige the possibilities of landscapes. His first landscape series (late 1820s) was Famous Places in the Eastern Capital, simple popular views of spots in Edo (Tokyo). The series was so successful, it encouraged Hiroshige to pursue landscapes as his main subject matter.

After the famous Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido series, Hiroshige undertook many other different landscape series. However, the public clamored for more views of Edo. In 1856, after taking the vows to become a Buddhist monk, Hiroshige initiated a series of one hundred (actually up to 152) views of the eastern capital. Of these, 118 were published in the One Hundred Famous Views of Edo series.

|

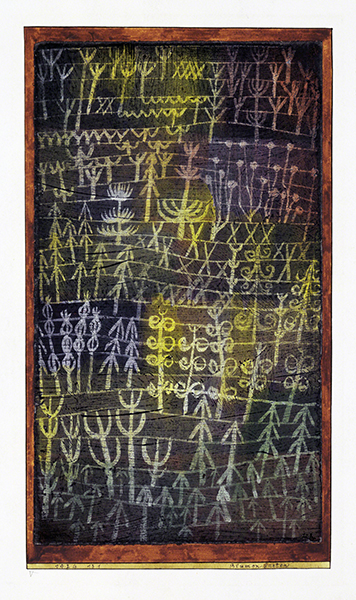

| Paul Klee (1879–1940, Switzerland), Flower Garden, 1924. Black paste ground with gouache and incising on paper, mounted on board, 17 ½" x 12 ¾" (44.5 x 32.4 cm). Image courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (MOMA-P1258klars) |

I include Paul Klee not only because he was a friend of my great-aunt, Tante Helena, but also because the free spirit in his works is something that inspires my own painting to this day. This should be a clarion call to all artists to follow inner vision, even if it doesn’t follow any current “trends.”

Architecture, gardens, and castles are a large part of Klee's body of work. Many of the works of architecture are based on reminiscences by the artist, while others are fantasy arrangements of natural forms in almost total abstraction, like Flower Garden.

In this work, like many of the early 1920s, he painted brilliant colors in a random (though color balanced) arrangement, covering these colors with black pigment. He then incised the floral form through the black pigment, exposing areas of bright color.

Like Cathedral of the same year, Klee organized his compositional space vertically, much as children and naive artists do. The floral forms provide a grid-like network similar to the network of architecture lines in Cathedral.

Klee's unique artistic vision was part of his transcendental idea that the material world was one among many realities open to an artist's awareness. His art was meant to open a window into those various other worlds in his philosophical principles. Although Klee's musician parents hoped that their son would follow in their footsteps, Klee knew from a young age that he wanted to be a visual artist. His early academic training focused on printmaking and drawing. Ultimately, he studied painting in Munich with the Symbolist Realist Franz von Stuck (1863–1928).

Klee remained isolated from modernism until he met Vasily Kandinsky (1866–1944) in 1911, along with other members of the German Expressionist group The Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter). Unlike the other major Expressionist artist groups that emphasized emotional turmoil, edgy urban scenes, and subjects of violence, The Blue Rider artists emphasized folk culture, romanticized past periods such as the Middle Ages, and, above all, demonstrated an attraction to spirituality. Klee exhibited with the group, and in 1912 was exposed to the work of avant-garde artists from Paris such as Pablo Picasso, Robert Delaunay, and Georges Braque. His experiments in abstraction started at that point.

Music, childhood, Swiss folk tales, and a general acceptance—rather than condemnation—of grief and pain as an integral part of the human condition all influenced Klee’s work. Perhaps most of all, music for Klee played a key role in his work, which was only rarely completely non-objective abstraction. For Klee, color had the same power as music. Becoming a teacher at the Bauhaus school in 1920, he taught students to compare the visual rhythm in drawings to the percussive rhythms in music.

Comments