Hanami in Spring: Terasaki Kōgyō, Katsushika Hokusai, Shibata Zeshin

With warm weather finally starting to return, I’m going to continue to celebrate spring with ART. Hanami is Japanese for “blossom viewing,” and is the name given to the annual spring cherry blossom viewing that takes place in Japan between March and May/June. The time span is wide because of the many species of sakura (cherry blossoms) that have different blooming times, and some of very short duration. The Japanese gave the United States government more than 3000 cherry trees in 1912, and those have their own Hanami in Washington, DC every year. Naturally, cherry blossoms play a big part in Japanese art.

|

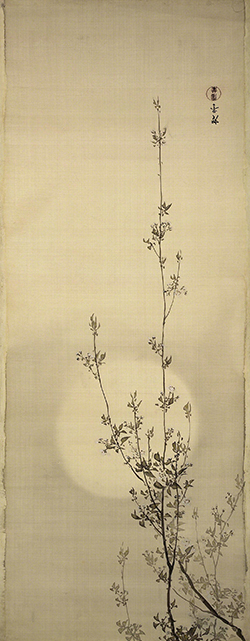

| Terasaki Kōgyō (1866–1919, Japan), Cherry Blossoms and Moon. Ink and light color on silk, 46 ¾" x 18 3/16" (118.8 x 46.2 cm). © 2017 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (MFAB-1017) |

The beautiful painting above is by an artist who is part of the interesting state of society in late 1800s Japan. While the country was industrializing and “modern(western)izing” at a fantastic rate, there was a lot of push back from Japanese who wanted to preserve traditional aesthetics and values. The veneration of the cherry blossom period is so lovely, it has resulted in masterpieces like this. In Japan, the cherry blossom is the symbol of, naturally, rebirth. In fact, I think I read somewhere that the school year in Japan starts in Spring rather than Autumn, because it is such an auspicious time.

Tersaki was born Terasaki Chutaro in Kyoto, the son of a poor samurai who was in service to a regional warlord (daimyo). Kyoto was the center of the Maruyama/Shijō “school” of painting that was both a reaction to and receptive of Western influence. It evolved out of the work of Maruyama Okyō (1733–1795), a painter school in the traditional Kanō School, who followed the traditions of Nanga (Southern School, or, traditional Chinese monochromatic painting), but who instilled in his work a respect for naturalism through direct observation. He also adapted techniques of Western chiaroscuro (nuances of dark and light) to build form. Terasaki, too, was trained in the Kanō tradition before moving to Edo (Tokyo) in 1888.

In Edo Terasaki studied with the Maruyama/Shijō painter Sugawara Hakuryu (1833–1898). Training with Sugawara combined with his Kanō training helped Terasaki develop a unique personal style. This piece probably pre-dates 1893, the year a fire destroyed his body of work in his studio. He thereafter decided to abandon traditional forms of expression and focused on images of beautiful women (bijin) in a more westernized style and book illustration. This painting of cherry blossoms in moonlight definitely reveals the influence of the Maruyama/Shijō style in the sophisticated nuances in value.

|

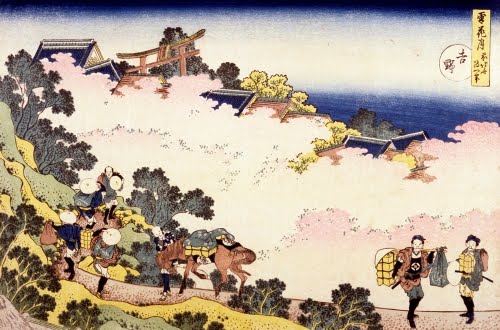

| Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849, Japan), Cherry Blossoms at Yoshino, from a Snow, Moon and Flowers series, ca. 1832–1833. Color woodcut print on paper, 9 13/16" x 14 15/16" (25 x 38 cm). © 2017 Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-1407) |

I’m sure none of you questions that I have a soft spot for the founders of the landscape genre in the ukiyo-e style, Hokusai and Hiroshige to be specific. They just seem to capture such elegant, subtle statements of visual experience—such as falling rain and snow, mist, and clouds—that it is no wonder this charming piece is so magnificent. Of course, this print is also a tribute to the artists who actually cut the woodblocks with Hokusai’s drawing and achieved the beautiful nuances in pinks of the blossoms! If you’ve ever seen the cherry blossoms in DC, this is what they look like from a distance.

Hokusai is credited with creating the importance of landscape and bird-and-flower prints in ukiyo-e. Born the son of an artist, he began drawing in earnest at the early age of five. He is thought to have learned drawing and painting from his father, who painted designs around mirrors he made for the shogun (the military dictator).

Hokusai’s lasting contribution to Japanese art, of course, was the introduction of landscape series of woodblock prints. His "Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji" had a lasting impact on the younger Hiroshige, and was so popular that it was published numerous times. His interest in landscapes started when he was in the Shunshō School. Impatient at having to produce actor prints, he studied the landscape tradition of the rival Kanō School, based in the great tradition of Japanese landscape painting.

Hokusai produced several Snow, Moon and Flowers and Snow, Moon, Wind and Flowers series. These poetic series usually contained references to revered poetry about these natural subjects, while featuring them in locations the Japanese traveling public would recognize. I love the wonky angle of the torii (gate) in the background of this print!

|

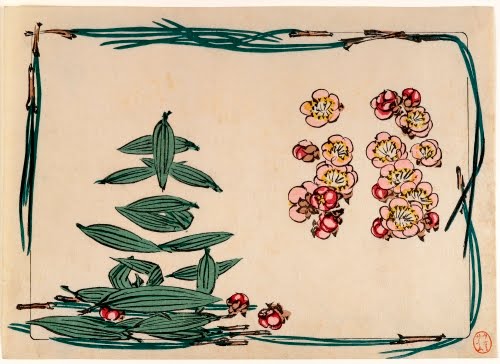

| Shibata Zeshin (1807–1891, Japan), Cherry Blossoms with Pine Needle Border, from the series Comparison of Flowers, ca. 1880. Color woodcut print on paper, 6 1/2" x 9 7/16" (16.5 x 24.5 cm). © 2017 Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-4635) |

Shibata Zeshin is such an interesting artist. This print reminds me of his New Year’s Cards (surimono). And those include precisely carved cursive Japanese to boot! Prints in series like this are not a scientific comparison of flora, like Western Florilegia, but rather aesthetic and symbolic. Cherry blossoms, symbols of fertility and rebirth, are a likely companion to the pine, which symbolizes strength and eternity (because it’s an evergreen, I guess). I particularly like the disassembled pine tree in the lower left, comprised of clumps of needles.

Shibata Zeshin lived through tremendous cultural and artistic changes in Japan after the US forced Japan open to Western trade in 1854. The Ansei Earthquake of 1855 destroyed much of Edo (Tokyo), and the Meiji “restoration” theoretically put authority back in the hands of an emperor rather than a military dictator (shogun).

Shibata was born in Edo, son of an ukiyo-e print artist who had studied under Katsukawa Shunshō (1726–1793). He began an apprenticeship at age 11 to a lacquer artist. At 13 he was apprenticed to the artist Suzuki Nanrei (1775-1844) to learn how to draw. While studying under Nanrei, he acquired the name Zeshin (“true artist”). He also studied in Kyoto, where he learned about Japanese history and Buddhist traditions, studying the tea ceremony, waka and haiku poetry, and philosophy.

Perhaps because of his training in Kyoto, Shibata resisted the urge to study Western art after 1853 and persisted in paintings that reflected Japanese tradition. He is one of the most traditional of the late artists who worked with Ukiyo-e themes. However, his insistence on tradition makes prints such as this one put Western influence in the rear-view mirror.

Comments