ART for the Bleak Midwinter: Camille Pissarro

To quote the title of an old British Christmas dirge (and, I do mean dirge), In the Bleak Midwinter is where we stand right now. But, that doesn’t mean we can’t look at a gorgeous painting of winter to keep our spirits up!

And, of course, it’s always more interesting when there’s a fabulous backstory to the artists I post. As much as I love the paintings of Monet and Sisley, I think Pissarro is my favorite Impressionist. What is so endearing about this artist—aside from the thrilling color in his paintings—was his fervent commitment to Impressionism (and the destruction of the Old Order of the Academy), as well as his encouragement and mentoring of his fellow Impressionists, even though he was far from a rich artist in the beginning.

|

| Camille Pissarro (1830–1903, France), Rabbit Warren at Pontoise, 1879. Oil on canvas, 23 5/16" x 28 7/16" (59.2 x 72.3 cm). © 2017 Art Institute of Chicago. (A7275) |

Not all of the Impressionists were born in France. Pissarro was born Jacob-Abraham-Camille Pissarro in Saint Thomas, Virgin Islands, then part of the Danish West Indies (I didn’t know the Danish had colonies). His father was a Sephardic Jew, a French citizen of Portuguese descent, and his mother was French. As a young man, he spent much of his time drawing. In 1842 he was sent to boarding school in France, where he quickly attained a love for old master paintings. After returning to Saint Thomas for a brief stint running his father’s business, he returned to Paris in 1855 to study art.

Pissarro was one of the artists who—disgruntled with the rigid conservatism of the French Academy—pushed for more progressive (though not officially recognized) artists to form a break-away group to exhibit their work. This group eventually included all of the major Impressionists. The thirty artists who exhibited for the first time in 1874 included Monet, Renoir, Sisley, Degas, and Cézanne. It was called the “Society of Anonymous Painters, Sculptors, Engravers, Etc.”

|

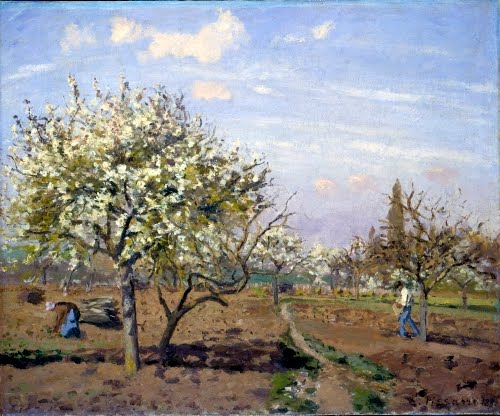

| Camille Pissarro, Orchard in Bloom, 1872. Oil on canvas, 17 3/4" x 21 9/16" (45.1 x 54.9 cm). © 2017 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. (NGA-P1157) |

Among the many reasons Pissarro and his fellow Impressionists rejected the Academy was because landscape painting and genre scenes were lowest on the list of works to be accepted. Also, the intimate scale of Impressionist works, usually painted outdoors, were dwarfed by the gigantic and grandiose history and classical painting subjects. This early work already shows the high-key Impressionist palette creeping into Pissarro’s work during the period when he was first associating with Monet and Sisley. While he’s depicting a subject dear to his heart—working people in the country—look at the gorgeous cobalt violet in the shadows. Yes, the Impressionists liberated painters from adding black to shades!

|

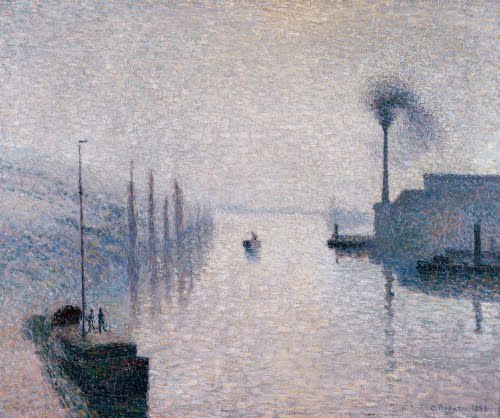

| Camille Pissarro, L’ Île Lacroix, Rouen (The Effect of Fog), 1888. Oil on canvas, 18 3/8" x 22" (46.7 x 55.9 cm). © 2017 Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-2751) |

By the last Impressionist show of 1886, the group was dominated by artists whose style would now be called Post-Impressionist. Chief among them were Signac and Seurat, whose works were exhibited separately. It was during the 1886 exhibit that Seurat showed his landmark A Sunday on La Grande Jatte — 1884. Pissarro himself showed Neo-Impressionists paintings at the last exhibition. He had moved to Eragny on the Epte River from Pontoise, and there met Georges Seurat (1859–1891) and Paul Signac (1863–1935), who had developed a painting style that conveyed the Impressionist obsession with perceived light and color in a scientific, rather than objective, manner. Eager to reinvent Impressionism, Pissarro adapted the style, until he tired of it in 1889 and returned to what he found most conducive to his pictorial frame-of-reference.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 4: 4.21; Explorations in Art Grade 6: 2.studio 7-8; A Community Connection: 4.4; A Personal Journey: 5.4; A Global Pursuit: 6.4; The Visual Experience: 16.4; Discovering Art History: 13.1, 13.2

Comments