Jewish American Heritage Month 2024

May was proclaimed Jewish American Heritage Month in 2006 to celebrate 350 years of Jewish contributions to American history and culture. To celebrate Jewish contributions to American art, this week I am showing you two vastly different Jewish Americans. Elise Asher was a lyrical abstractionist active in the Feminist Art Movement. Philip Evergood was a Social Realist whose compassion for less fortunate people led him to create artworks that tackled a whole range of social issues in the United States.

|

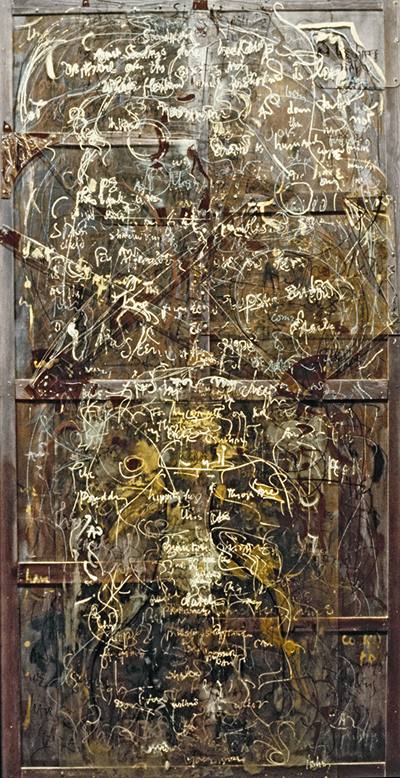

| Elise Asher (1914–2004, U.S.), Sunday, 1972. Oil on Plexiglas over oil on canvas, 68 ⅛" x 35" (173 x 89 cm). Photo courtesy of the artist. © 2024 Artist or Estate of Artist, licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (8S-16724asvg) |

Asher explained that her paintings are her own physical immersion in her poems. She began painting on Plexiglas around 1965. In her large paintings of the 1970s, her works evolved into multiple-layer structures in which both private fantasy figures and fantasy calligraphy coexist in a mystical mélange. She felt that such combinations of elements write their own script and provoke a great contradiction. She said that her paintings “relive and relieve” her special “woman-fears” and frustrations that were once expressed in her poems. The aim of Asher's works was opulence, imitating traces of a tapestry of written and visual language.

By the mid- to late-1960s, art movements began to reflect the collapse of the mainstream American art world dominated by the market-driven, commercially oriented, male-dominated Abstract Expressionists. The 1970s marked the beginning of the Feminist Art Movement. The questioning of the political, racial, and social status quo led women in increasing numbers to protest against gender inequality. Several books, including The Feminine Mystique (1963) and The Female Eunuch (1970), helped raise awareness of women’s experiences.

Women artists, art historians, and critics began to organize and protest discrimination against women artists at this time. They formed cooperative galleries, university feminist art programs, and coalitions that published art journals and reviews of women’s art. These efforts were complimented by a widespread public desire to see more open, pluralistic, and humanistic art.

In 1972, the Women’s Caucus for Art was formed by a group of women artists. The group gave women a forum to explore issues surrounding women artists and art history. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art landmark traveling exhibition Women Artists 1550–1950 in 1977 was a major steppingstone toward equality of representation of women artists, although it would take into the 1980s for greater strides to be made.

Born in Chicago, Asher began her creative career writing poetry. In 1955, she published her first poetry volume, The Meandering Absolute. According to Asher, her unique painting process is an attempt to “translate the poetry of existence, its beauty and its terror, into a vocabulary of the visual imagination. This painted transformation seeks a more than usual state of being, the condition of otherness.” (June Kelly Gallery via MutualArt)

Asher moved to New York’s Greenwich Village in 1947. There, she became immersed in the Abstract Expressionist and Beat Poet scene. Using her poetry as inspiration, she ultimately tried her hand at painting. Asher experimented with the connection between word and image, scribbling bits of text through her paintings, which were mystical landscapes in a vivid palette. In some works, she combined her illegible scribbling with animal and bird forms, producing works that were a cross between the gestural painting of Abstract Expressionism and Surrealism.

|

| Philip Evergood (1901–1973, U.S.), Don’t Cry, Mother, 1938–1944. Oil on canvas, 26" x 18" (66 x 45.7 cm). Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2024 Artist or Estate of Artist. (MOMA-P2072) |

In his haunting style of Social Realism, Evergood often tackled societal issues such as poverty, disability, and age. The artist frequently used skewed space to emphasize the theme. In Don't Cry Mother, the out-of-proportion right arm of the woman leads the eye to the hungry children, while empty plates explain her anguish.

Because this work was painted during World War II (1939–1945), it is possible that Evergood was referencing the plight of European refugees, although he appears to depict an African American family. The ruined house may recall cities destroyed by bombings. This work may also reference the compounded suffering of Black people toward the end of the Great Depression (1929–1940).

Born in New York to a British mother and Australian father of Polish Jewish descent, Evergood moved to England with his family in 1910. His father, artist Miles Evergood (1871–1939), changed the family name from Blashki to Evergood in 1915. Evergood studied art in London and returned to New York in 1923 to study under Ash Can School painter George Luks (1867–1933) at the Art Students League.

Studying further in Paris, Evergood was impressed with the works of Realism’s satirist Honoré Daumier (1808–1879), Post-Impressionist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1863–1901), and Flemish Renaissance genre painters Hieronymus Bosch (died 1516) and Pieter Bruegel, the Elder (ca. 1525–1569). These artists all depicted unvarnished scenes of everyday life. In the 1930s, Evergood went to Spain, where he was impressed by the work of Romanticist Francisco Goya (1746–1828) and Spanish Renaissance painter El Greco (1541–1614).

Evergood’s mature style was a combination of social commentary and purposely awkward compositions. This style evolved during the Great Depression, when Evergood worked for the Federal Art Project from 1934 to 1937. Sophisticated intent was wed to an intentionally crude technique often characterized by jagged, though delicate, lines.

Interestingly, Evergood remained a figurative artist even though the prevailing trend during most of his career was Abstract Expressionism. After the 1940s, Evergood moved away from social commentary and produced works that seemed part fantasy, part reality. Despite the change in theme, he continued to use the distortions and exaggerations of his Social Realist work.

Comments