Survey No. 10: Ubiquitous Real

So far we have taken a look at Classicism and Romanticism around the world in the 1800s. Now let’s look at “realism,” which—like every other style—has been a trend somewhere on Earth in art since antiquity.

“Realism” is not just a stylistic term defining an art movement—mainly in France—in the 1850s and 1860s. I dare say realism is seen in the art of every culture on the face of our planet, in varying degrees of emphasis through time. For the last time, let’s examine a Western artistic style enshrined in art history survey books, in the context of similar impulses in non-Western cultures at the same time. Once Impressionism hits, our “new slant” will take on a different tack.

|

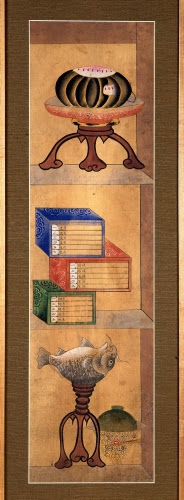

| Korea, Bookshelf, panel from a Chaekgado screen, 1850s. Colors on paper, 39 3/16" x 10 11/16" (99.5 x 27.2 cm). © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (MFAB-1299) |

For centuries, Korea played a pivotal role in the East, transmitting culture between China and Japan (especially in the field of ceramics). Always influenced by Chinese art after a thwarted Mongol invasion in the 1500s, Korea became a semi-independent state until it was invaded by Japan in 1910. During the 1700s, Chinese influence waned in Korea, and Korean painting came into its own. Everyday life and objects were one of the two most popular genres of Korean painting of the 1700s and 1800s, next to landscapes. Chaekgado is a late manifestation of the Joseon period (1392–1910). Chaekgado literarly means books and things.

This panel comes most like from an eight-fold or ten-fold screen. Both common people and nobility used such screens alike. The subject is the attributes of a scholar: books, paintings, ceramics, ink stones, pen containers, and musical instruments scattered in bookshelves. The subject itself is actually inspired by the reverence for scholars who esteemed learning and art above all else. This itself was a Chinese tradition, which had nurtured the whole school of “literati painting” of scholar/artists. The subject would have appealed to both commoner and noble alike. While the objects are realistically portrayed, their placement within each shelf is somewhat mystical, as if some of them are actually floating. The perspective within each shelf is typical of Chinese and Japanese painting and prints at the time.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 1: 1.4; Explorations in Art Grade 2: 5.27; Explorations in Art Grade 4: 6.36; Explorations in Art Grade 5: 2.8, 2.7-8 studio; Explorations in Art Grade 6: 1.6; A Personal Journey: 2.6; A Community Connection: 6.2; A Global Pursuit: 4.5; Discovering Drawing: 4; Experience Painting: 2; Exploring Painting: 9; Discovering Art History: 13 Activity 1; The Visual Experience: 9.3, 13.6

|

| Ren Yi (1840–1895, China), The Five Cardinal Relationships, 1895. Ink and colors on paper, hanging scroll, 73 3/16" x 38 1/4" (185.9 x 97.2 cm). © Art Institute of Chicago. (AIC-385) |

Landscape and nature painting in Chinese art are the centuries-old subject of constant debate and analysis by scholars and artist-scholars. By the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912), nature painters were loosely divided into “traditionalists” and “individualists.” Ren’s work lies somewhere between the two strains.

Ren was the son of a rice merchant, but trained as a painter. His favorite subject matter was landscape, but he supplemented his income doing portraits. While his early style was emblematic of the tight compositions of classic Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE) landscapes, his later works, such as this, took on the abbreviated brush strokes, suggestion of space and form, and wet application of paint of such earlier Qing masters as Zhu Da (1626–1705).

This painting represents, in bird symbolism, the Five Virtues or Cardinal Relationships. These follow the Confucian belief that implementation of proper hierarchies in social groups leads to social harmony. The long tailed phoenix in the upper right represents benevolence (ruler and subjects); the two cranes in the middle represent longevity (filial piety); above the cranes are orioles representing propriety (sibling relationship); the swimming ducks represent fidelity (martial loyalty); and the two wagtails above the ducks are friendship.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 1: 4.connections; Explorations in Art Grade 2: 3.13, 3.14, 3.16; Explorations in Art Grade 3: 5.26, 5.25-26 studio; Explorations in Art Grade 5: 4.21; A Personal Journey: 5.5; A Community Connection: 6.2; A Global Pursuit: 4.5; Experience Painting: 4; Discovering Art History: 4.3; The Visual Experience: 9.3, 13.4

|

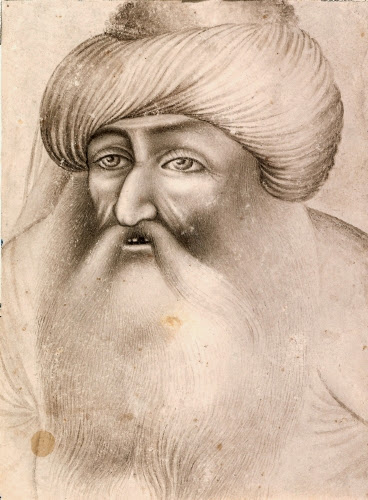

| Iran, Portrait of a Man in a Turban, mid-1800s. Ink wash or watercolor on paper, 5 5/8" x 4 3/16" (14.4 x 10.6 cm). © Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY. (AK-822) |

The long tradition of painting in Iran first developed in manuscript illumination. The great period of literary illustration occurred during the Timurid (1350–1502) and Safavid (1502–1736) Dynasties. However, during the 1600s, book illustration was replaced in importance by individual works of art, in part because they were less costly than lavishly decorated books. While an elegant, stylized court style persisted in individual paintings and drawings, an inherent Iranian interest in realism led to whole new genre in Iranian art that focused on everyday life.

This painting displays an interest in monumentality through chiaroscuro, which may have been influenced by Western art. This depiction of an older man pays particular attention to his particular physical characteristics, such as missing teeth. The interest in unflinchingly realistic portrayal of the not-so-beautiful aspects of life was a trend that also became popular in Mughal art in India.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 2: 2.8; Explorations in Art Grade 3: 1.2, 1.3; Explorations in Art Grade 5: 1.1; Explorations in Art Grade 6: 1.2; Discovering Art History: 4.7, 7.3; The Visual Experience: 9.2, 14.2

|

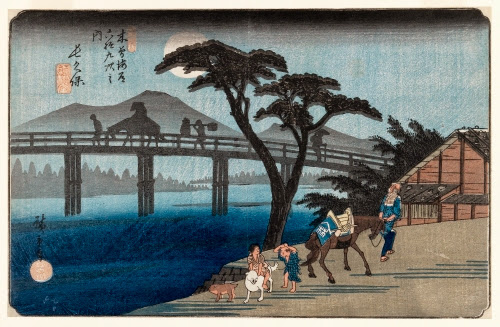

| Utagawa Hiroshige I (1797–1858, Japan), Nagakubo, #28 from the series Sixty-Nine Stations of the Kisokaido, 1834–1842. Color woodblock print on paper, 9" x 13 13/16" (22.9 x 35.2 cm). © Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-2810) |

When one thinks of the ukiyo-e style in printmaking, one usually conjures up images of kabuki theater actors, great beauties, and literary scenes. Landscape subjects only became popular during the early 1800s, in great part because of the work of Hiroshige I and Hokusai (1760–1849). Ukiyo-e prints were primarily an art form for the middle class. Most middle class art patrons could not afford painted landscapes by the various schools connected primarily to the emperor’s court, so the subject was translated into the woodblock print medium.

The importance of landscape painting was passed on from Chinese art. While woodblock prints were geared toward middle class patrons, artists such as Hiroshige I observed the same conventions in landscape as did painters. As in painting, distance is implied by misty distant forms, in this case by parts of the woodblock being rubbed to remove most of the ink. Small genre scenes, strong diagonals leading into the background, and a focus on trees in importance are age-old elements important to landscape depiction.

Series such as the stops on the Kisokaido were meant to remind viewers of the scenic beauty of the road between Kyoto and Edo. Like many landscape artists around the planet, Hiroshige I manipulated his views of the route to create a pleasing composition, while maintaining the integrity of important recognizable landmarks.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 1: 4.21, 1.connections; Explorations in Art Grade 2 1.1; Explorations in Art Grade 4: 1.5, 1.6, 4.21; A Community Connection: 4.5, 8.2; A Global Pursuit: 7.5; Experience Printmaking: 3, 4; Discovering Art History: 2.2, 4.4; The Visual Experience: 3.5, 9.4, 13.5

Western Artists of Realism You Might Not Have Encountered:

Realism was an important style outside of countries where it revolted against Neoclassicism. Plus, I’ve included one of the French Realists who does not often make it into standard surveys of Western art history.

|

| Piotr Michalowski (1800–1855 Poland), Old Man from a Village, ca. 1846–1848. Oil on canvas. National Museum, Warsaw. (8S-7423) |

Before the 1700s, Poland, like Russia, had major painting schools attached to noble patrons in major cities. After the partition of Poland in the 1700s and 1800s, the major cities, such as Krakow, ended up as part of partitions of Austria, Russia or Germany. Krakow enjoyed a brief period of autonomy after Napoleon’s final defeat (1815), until 1830 when it was crushed and placed back within the Austrian partition. These dramatic and disheartening events produced a sort of national romantic yearning for a united Poland, which affected Polish painting. This Romanticism was tempered with an inherent, down to earth realism in certain subjects.

Piotr Michalowski is considered a leading painter of Romanticism in Poland because of his history paintings about Napoleon. Napoleon was, oddly enough, revered in Poland because he had busted much of the Russian and Austrian partitions (by conquest, naturally), and had established Polish cities as independent city-states. Aside from his history paintings, however, Michalowski did numerous studies of everyday people in Poland, especially members of Poland’s large Jewish population.

Michalowski’s portraits are sympathetic and honestly rendered. The only drama going on with these works is the usually dramatic lighting, and vigorous brushwork. These elements influenced Michalowski’s work when he studied in France and became interested in the work of Dutch, Spanish, and Flemish Baroque masters.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 3: 1.1, 1.2, 1.1-2 studio; Explorations in Art Grade 4: 1.2; Explorations in Art Grade 5: 1.1, 1.2; Explorations in Art Grade 6: 1.2; Exploring Painting: 9; A Community Connection: 2.3, 6.2; A Global Pursuit: 6.4; Experience Painting: 6; Exploring Painting: 7; Exploring Visual Design: 9; The Visual Experience: 9.3, 16.4

|

| Fidelia Bridges (1834–1923, US), Bird’s Nest and Ferns, 1863. Oil on panel, 7 7/8" x 6 9/16" (20 x 16.8 cm). © Art Institute of Chicago. (AIC-289) |

Fidelia Bridges, born in Salem, MA, studied painting under William Trost Richards (1833–1905) in Philadelphia. At the time he was influenced by the English Pre-Raphaelite movement that emphasized a detailed study of nature with botanical accuracy. This work is very much in the same spirit as the work of the English Pre-Raphaelite William Webbe (active 1853–1878).

Bridges set up her own studio in Philadelphia in 1862. Richards sponsored her among his wealthy patrons there. At this time she was exhibiting at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. In 1867 she went to Rome for a year and joined a group of women artists who wished to work without the strictures of American society. After this trip Bridges began to form her mature style, quite apart from Richards’ influence.

Bridges turned entirely to watercolor in her later. Her work varied little in subject matter throughout her career: close-ups of small fragments of nature such as flowers, grasses, and birds focusing on minute details in vibrant colors.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 1: 4.connections; Explorations in Art Grade 2: 1.2, 1.1-2 studio, 3.15; Explorations in Art Grade 4: 4.21-22 studio; Explorations in Art Grade 5: 4.19; Explorations in Art 6 2.9; A Community Connection 5.4, 6.2; Experience Painting 6; Exploring Painting 9; Discovering Art History 12.3; The Visual Experience 9.3; 16.4

|

| Narcisse-Virgile Diaz de la Peña (1807–1876, France), Trees and Pool, ca. 1840–1850. Oil on panel, 8 5/16" x 12 3/16" (21.1 x 31 cm). © Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-1219) |

Narcisee-Virgile Diaz de la Peña was a leader of the so-called “Barbizon School,” a group of Realist landscape painters who worked in the commune of Barbizon near Fontainebleau Forest, from which they derived much of their inspiration. In Realism’s rejection of academic admonition to define everything by strict formulas, ignoring nature around them, artists such as Diaz de la Peña moved to Barbizon in order to be close to nature and capture landscape faithfully.

Diaz de la Peña began as a decorator of ceramics but began painting landscapes when he met the Barbizon painters. His enthusiasm for the landscape painting school eventually led him to mentor younger artists, some of them future Impressionists such as Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919).

Like many of the Barbizon Realists, Diaz de la Peña was influenced by Dutch Baroque landscape painting, and the works of the English Romantic landscapist John Constable (1776–1837). The Dutch landscapists worked directly outside to produce studies for landscapes, while Constable often painted entire compositions outside. Eventually, Diaz de la Peña and many of the other Barbizon painters painted en plein air, a major influence on Impressionism.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 1: 4.21, 4.connections; Explorations in Art Grade 2: 1.1, 1.4; Explorations in Art Grade 4: 4.21, 4.22; Explorations in Art Grade 5: 4.19; Explorations in Art Grade 6: 2.7, 2.7-8 studio; A Personal Journey: 5.4; A Community Connection: 5.4, 6.2; A Global Pursuit: 6.3, 6.4; Discovering Art History: 12.3; The Visual Experience: 9.3, 16.4

Comments