Survey No. 9: What is Romanticism?

Last week I discussed the stylistic designation “classicism” in both Western and non-Western art produced in the 1800s. For today’s New Slant on Art History, I continue to look at these terms used to classify art of the 1800s: Romanticism. This has actually been a trend in art since antiquity.

“Romantic” is from the French meaning “novel like” (roman is novel in French). It does not necessarily refer to love-relationshippy (a word?) type of stories, but more in the spirit of anything that is adventurous or dramatic. Whipping up a style name from “romantic” (Romanticism) is a way of characterizing, in Western art, the rejection of the conservative strictures of Neoclassicism during the second quarter of the 1800s. Romantic artists preferred drama, open compositions, movement, bright color, fluid brush strokes, exotic subject matter…in other words, Excitement. Let’s see that spirit in Non-Western examples…

|

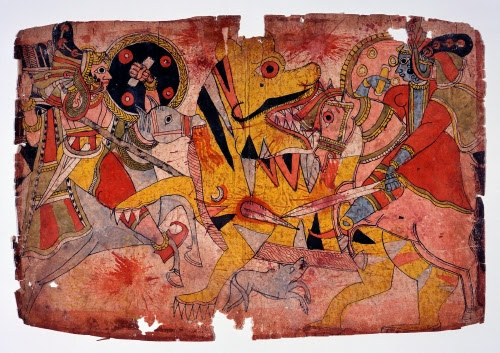

| India, Gods in Battle with a Tiger, scene from the Mahabharata (Ancient Epic of India), probably from Maharashtra, ca. 1830–1850. Watercolor on paper, 11 1/4" x 16 1/2" (28.6 x 41.9 cm). © Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY. (BMA-1003) |

After the fall of the Mughal Empire around the mid-1700s, the many small kingdoms they had conquered resumed semi-autonomy and their painting schools flourished anew. Maharashtra was one of the most active of these centers, with a distinctive, abstract style. It may just be me because I look at too much art, but these figures are depicted in a manner that reminds me of Mesoamerican figures, especially in the elaborate head ornament. And no, I’m not suggesting cross-cultural influences!

I’m not sure if any of the European Romantic painters ever tackled sacred Hindu texts, but, boy, would they have a treasure trove of exciting narratives to illustrate! The “Mahabharata” was one of two great epic Indian texts that chronicled the merging of spiritual and historical events in ancient India. The style of this manuscript has a wonderful, abstract quality in the stylized figures with wide, staring eyes, the flattened forms, and the lack of pictorial space. Compare the stylization of this tiger to Japanese, Korean, or Chinese renditions of the animal.

The “Mahabharata” achieved its final form around 400 CE, but is thought to have been compiled starting around 400 BCE. Many scholars consider it a valuable insight into the early development of Hinduism. The tiger is mentioned often in the “Mahabharata,” particularly when it refers to a person’s either physical (“tiger-wasted Bhima”) or moral strength (“valor that was tiger-like”). This scene is most likely from one of the adventures of Krsna (blue-skinned). It has all the elements that would qualify as romantic: dynamic action, drama of the hunt, exotic garments, and shallow picture plane that forces the viewer’s attention on the dramatic event.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 1: 3.17; Explorations in Art Grade 2: 4.19; Explorations in Art Grade 3: 3.studio 17-18; Explorations in Art Grade 5: 5.27; Explorations in Art Grade 6: 3.16, 3.18, 3.connections; A Community Connection: 6.2; A Global Pursuit: 3.5; Communicating through Graphic Design: 5; Experience Painting: 1, 2

|

| Utagawa Kunisada (Toyokuni III) (1786–1864 Japan), Ichikawa Danjūrō as Unno Kotarō Yukjuji Disguised as Yamagatsu Buō, from the play The Barrier Gate, at the Ichimuraza Theater (Edo), 1828. Color woodcut with extensive use of metal pigments on paper, 8 1/4" x 7 7/16" (21 x 18.9 cm). © Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY. (BMA-2671) |

Utagawa was one of the most popular artists of prints in the ukiyo-e style. Ukiyo-e means pictures of the floating world in the sense of the transience of earthly pleasures such as beautiful people and Kabuki theater drama. He was also a book illustrator and painter. As many Japanese artists did to honor their teachers, he took the name of his, Utagawa Toyokuni (1769–1825). Much like contemporary magazines about popular culture such as “People” or “Us Weekly,” these prints were collected by people and displayed in the home.

If you’ve ever seen a kabuki play, then you realize, like grand opera in the West, there are a lot of exciting, tragic tales told. There are also a lot of battles and fights, all choreographed in the most amazing dances. Diagonal compositions like this were a big influence on Romantic artists in the West, and especially on Impressionists. In the iconography of the actor prints, when eyes are crossed it usually indicates the moment of highest drama. In this particular play, Unno wields a massive ax in a fight with another character.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 1: 3.studio 13-14; Explorations in Art Grade: 2 4.19, 4.20; Explorations in Art Grade 3: 1.3, 3.studio 17-18; Explorations in Art Grade 4: 1.2; Explorations in Art Grade 5: 1.4; Explorations in Art Grade 6: 1.1, 1.4, 3.16, 3.connections; A Personal Journey: 1.1, 1.3; A Community Connection: 8.2; A Global Pursuit: 7.5; Experience Printmaking: 3, 4; Exploring Visual Design: 1, 11, 12; The Visual Experience 9.4, 13.5; Discovering Art History 4.4

|

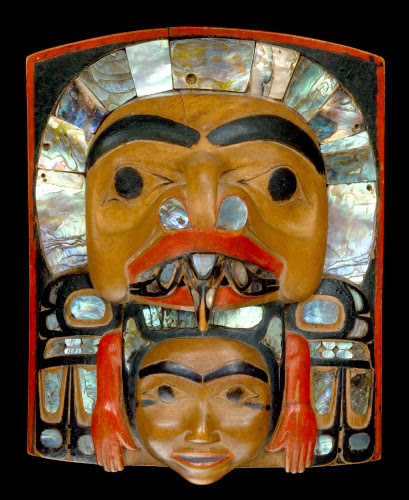

| Attributed to Simeon Stilthda (ca. 1799–1889, Haida Culture, British Columbia), Crest frontlet, ca. 1850. Wood, abalone shell, pigment, 7" x 5 3/4" x 2 ¼" (17.8 x 14.6 x 5.7 cm). © Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY. (BMA-5130) |

I am rather surprised that Western artists of the Romantic bent—especially in the US—did not look right at their back door for inspiration, when the rich cultures of Aboriginal peoples surrounded them in the Americas. The iconography of the First Nations cultures’ art would certainly have appeared exotic to Western artists. Maybe the iconography and cosmology of the works were too sophisticated for Western tastes?

There is archeological evidence that the Haida people had a sizeable population as early as 5000 years ago. They inhabit areas off the coast of northern British Columbia and southern Alaska. One of the major art forms for the Haida culture was wooden sculpture. As is the case with the Indian painting, there is a wonderful sense of simplification and abstraction in these sculptures, while they impart important messages about the connection between humans and helpful spirits.

Simeon Stilthda was a major Haida artist active during the mid- to late-1800s. He is most famous for his masks, some of which bare striking similarities to portraits of actual individuals. Crest frontlets such as this were not masks, but rather headdress. They were worn by high-ranking clan members for welcoming dances, ceremonies, and potlatches. This frontlet represents a spirit (upper earth) and a human (middle earth). Abalone was often used to indicate a spirit being having a sort of nimbus (halo).

Correlations to Davis programs: A Community Connection: 3.2; A Global Pursuit: 2.1, 2.5; Beginning Sculpture: 5; The Visual Experience: 10.2, 14.5; Discovering Art History: 4.10

Happening in Western Art History: Romanticism

Although France is seen by Western art historians as the center of the Romanticism movement in art, the romantic impulse is never far from the artists of every culture in the world. There is often an interest in subject matter that elicits emotion because of drama, danger, excitement, heroics, or jarring color and form. Romanticism can also be characterized by an interest in sentimentality, awe, or even national pride.

|

| Jan Nepomucen Glowacki (1802–1847, Poland), Morskie Oko Lake in the Tatra Mountains, ca. 1837. Oil on canvas. © Muzeum Narodowe, Kracow, Poland. (8S-7413) |

Poland was practically partitioned out of existence permanently between the 1700s and 1800s by Russia, Austria, and Germany. The dividing up of Poland’s territory to the various European powers left the Poles with a yearning to cherish their own land that had slipped through their fingers because of wars and power grabs in central and eastern Europe at the time. Poland was not restored as a sovereign country until 1918. In the meantime, many Polish artists became prominent focusing on Polish subject matter.

Jan Nepomucen Glowacki is considered the father of painting the Polish landscape in Poland. He trained in Krakow, Prague, Munich and Rome, absorbing all of the current trends in painting and returned to Poland to teach in Krakow. While in Italy he saw the works of artists such as Bernardo Bellotto (1720–1780), who painted detailed views of Poland before the partitions, and it inspired him to likewise portray Poland for foreigners to marvel at.

Glowacki is most noted for his many depictions of the Tatra Mountains. While his landscapes are realistic depictions of actual places, like the Hudson River School artists, he manipulated and compressed compositions for maximum impact on the viewer, a type of Romantic-Realism. The romantic element is heightened by the cross on the lower left, a symbol that Poland was indeed God’s country, and a country worth reuniting.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 1: 4.connections; Explorations in Art Grade 2: 1.4, 1.5; Explorations in Art Grade 4: 4.21, 4.22; Explorations in Art Grade 5: 4.19; Explorations in Art Grade 6: 2.7, 2.8, 2.studio 7-8, 2.connections; A Community Connection: 6.2; A Global Pursuit: 6.4; Experience Painting: 6; Exploring Painting: 11; The Visual Experience: 9.3, 16.4.

|

| Karl Bodmer (1809–1893, Swiss), Scalp Dance of the Minitarres, from the Travels in the Interior of North America portfolio, printed by Ackermann and Company (London). Aquatint and etching on paper, 11 13/16" x 17 5/16" (30 x 44 cm). © Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Bayou Bend Collection. (MFH-777) |

Having just posited about why Western artists did not use First Nations as subject matter more during the 1800s, we come to Karl Bodmer. Just as the lives of Arabs or Greeks or Africans would have been the topic of much wild speculation by European art aficionados during the Romantic period, so, too, were Aboriginal peoples of the US. They were considered especially “exotic” because they were “not civilized.”

Bodmer was a classically trained artist, who studied in Paris before he went to Germany to sketch landscapes. While there he met a German naturalist-prince who convinced him to accompany an expedition to produce accurate depictions of the western US and document what he saw as vanishing cultures. The 1832 expedition, which mimicked the route of both Lewis and Clark and George Catlin, encountered numerous native cultures, among them the Hidatsa (called “Minetarree” by the prince) in what is now North Dakota. The Hidatsa were practically wiped out by Western smallpox between 1837–1838 and joined with the Mandan culture.

Bodmer made copious sketches for 81 paintings that he produced when he returned to Europe in 1834. This depiction of a dramatic moment in the scalp dance was sketched by Bodmer at Fort Clark, ND, in 1834, in a number of drawings of individuals and groups of individuals. Bodmer’s over 400 sketches from the trip were published in print form between 1839 and 1843.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 1: 5.27; Explorations in Art Grade 3: 1.3, 1.4; Explorations in Art Grade 4: 1.2; Explorations in Art Grade 6: 6.studio 35-36; A Community Connection: 6.2; A Global Pursuit: 6.4; Experience Printmaking: 5; The Visual Experience: 9.4, 16.4; Discovering Art History: 12.2

|

| James Renwick (1818–1895, US), Smithsonian Institution, 1849. Washington, DC. © Davis Art Images. (8S-6864) |

And finally, what could be more romantic than harking back to the past good-old-days for stylistic advice? Starting during the Romantic period, a number of past architectural styles were revived as an offshoot of the Neoclassicism that continued to dominate many public buildings. Often, revival styles were mixed together in one building, such as Roman and Greek. The Smithsonian Institution is a mixture of Gothic and Romanesque revivals. Interest in the Gothic and Romanesque periods sprang from the Romantic obsession with medieval chivalry and literature, especially in Britain.

James Renwick, a child prodigy, trained as an engineer from the age of 12. He had grown up with cultured, affluent parents and was well trained in world (European) history and art and architectural history. Between 1839 and 1843 he worked as a structural engineer on the Erie Railroad. Although he had no practical design experience, he submitted the winning design for the Smithsonian Institution’s “Castle” in 1846. Although the Smithsonian trustees requested Romanesque Revival for the style, Renwick added some Gothic elements such as tall, narrow windows; rose windows; and vaulted ceilings. He also added Saxon and Norman decorative motifs.

Renwick’s vast knowledge of architectural history meant that most of his designs incorporated numerous styles in one building. This helped formulate a uniquely American style of revivalist architecture. Among the other famous buildings he designed are Saint Patrick’s Cathedral in New York and the Corcoran Gallery in Washington.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 1: 1.1; Explorations in Art Grade 2: 6.31, 6.33; Explorations in Art Grade 3: 4.20; Explorations in Art Grade 4: 3.18; Explorations in Art Grade 5: 2.11, 2.12; Explorations in Art Grade 6: 4.20; A Community Connection: 4.4; Discovering Art History: 12.2; The Visual Experience: 11.4

Comments