Survey No. 8: Neoclassicism

Art is produced steadily on a second-by-second basis throughout the world. In our art history survey, we are now entering the 1800s, a period in world history when the influence of art from non-Western countries came to the West, and Western art made its way into the language of art in the many parts of the world “colonized”/occupied by Western countries.

A look at the dominance of the Western aesthetic starting in the 1800s is unavoidable, as well as those neat little stylistic designations that Western art history books use to describe the art of the 1800s. However, these styles can also be viewed in terms of the history of art in non-Western cultures. Let’s start with the idea of “classicism,” extracted from the Western movement Neoclassicism that was popular in the first two decades of the 1800s.

The word “classic” refers to anything considered of the highest class or rank, serving as an outstanding example of a culture or aesthetic. It refers to anything that can be considered as a model of desirable taste or style. The word corresponds to accordance with generally accepted principles or methods in the arts. In essence, something that is classic is timeless and traditional in style or subject. Classicism is generally discussed when considering art that harks back to previous traditions. Thus, it is possible to discuss the relationship of a work of art from any culture in comparison to a historical style of that culture that is considered an aesthetic high point.

|

| Lu Yuan (1768-1848, China), Autumn Landscape, 1816. Ink on paper fan painting, 6 9/16” x 20 1/4” (16.8 x 51.4 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-3432) |

If there is another country outside of Western Europe and America that values a classical tradition in art, it is China. This is especially true in painting. Very few periods in Chinese art history did not see a significant focus on revitalizing time-honored styles in landscape painting. The Qing Dynasty (1644–1912), a period of extended political stability and economic prosperity, witnessed a significant refocus on traditional landscape painting, i.e. styles going back to the Song period (960–1279 CE).

There were two main strains in Qing painting, the traditionalists, who respectfully interpreted styles of past masters, and the individualists who produced powerful, more personal works that were often politically oriented. Lu Yuan was a traditionalist whose name may have been adopted (as artists did with artists they admired) from the Yuan dynasty (1280–1368). One of the “Four Masters of the Yuan Dynasty,” landscape painter Huang Gongwang (1269–1354) worked during that period. Like Yuan painting, Lu’s work is sketchy and seems to have been the result of use of a drier brush. Soft washes and fluid lines of Song painting were abandoned in favor of a romantic austerity of unpainted areas and sharp, dry-brushed forms.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 1: 4.connections, 4.21; Explorations in Art Grade 5: 4.20; Explorations in Art Grade 6: 2.7, connections, 2.studio 7-8; A Personal Journey: 5.5; A Community Connection: 6.2; Experience Painting: 4; Exploring Painting: 11; The Visual Experience: 13.4; Discovering Art History: 4.3

|

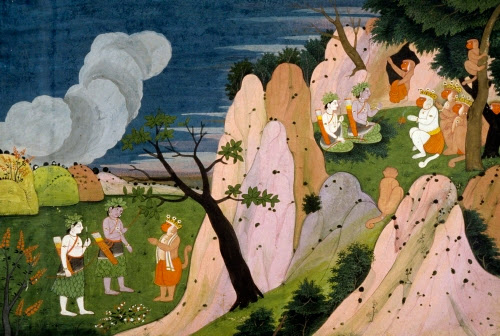

| India, Surgiva Takes Rama to the Mountain Cave where Sita’s Jewels are Kept, illustration from a Ramayana (Tales of Rama), from Kangra (?), Himachal Pradesh, ca. 1820. Opaque watercolor and gold leaf on paper, 9 3/8" x 13 1/2" (23.8 x 34.4 cm).© Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-1694) |

Painting in India flourished as early as 200 BCE in the form of fresco decoration in Buddhist cave complexes such as Ajanta. The Mughal period (ca. 1526–1756) ushered in Persian and European influence in painting, as well as an interest in scenes of everyday life of nobles and common people alike.

After the fall of the Mughal Dynasty in the mid-1700s, the various Rajput kingdoms of Himachal Pradesh experienced a revival of the classical Indian book illustration style. Much of the activity centered in Kangra where a lively painting “school” evolved. The style was influenced by Indo-Persian manuscript illumination of the Mughal period, which had been infused with ideas from Western art. This scene shows how the Indian tendency to construct space by “piling up” forms one atop another (vertical perspective) is used side-by-side with western-influenced diminution of forms into the distance by overlapping forms. There is also more attention paid to the relationship of figures to their environment.

The “Ramayana” is one of the great epics of Indian literature, chronicling the life of the virtuous king Rama and his wife Sita. This scene comes from the episode when Sita had been kidnapped by the evil king Ravana and Rama enlists the aid of the monkey king Surgiva to rescue her.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 1: 3.17; Explorations in Art Grade 2: 4.19; Explorations in Art Grade 3: 3.studio 17-18; Explorations in Art Grade 5: 5.30; Explorations in Art Grade 6: 3.16, 3.studio 13-14; A Community Connection: 6.2; A Global Pursuit: 3.5; Experience Painting: 1, 2; Exploring Visual Design: 5; Discovering Art History: 4.2; The Visual Experience: 9.3, 13.2

|

| Zuni Pueblo Culture, New Mexico, Water jar, 1820–1850. Slip-painted ceramic, 12 9/16" x 133/8" (32 x 34 cm). © Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-102) |

One of the classical and enduring art forms that is honored even more in the 21st century is the ceramic arts of the Pueblo cultures of the American Southwest. Like early Jomon wares in ancient Japan, Pueblo potters from the earliest times created utilitarian wares that were decorated with abstract motifs purely for decoration’s sake. The motifs came from nature, symbolizing the abiding reverence and connection held by Aboriginal peoples of the US to the present day.

The Zuni are thought to have been farmers in the region where they now live as long as 3000 years ago. They later came under the influence of Mogollon and Anasazi pueblo-building cultures. There are definite decorative connections among all of the Pueblo ceramic traditions. Another connection is the fact that ceramic artists were women, while the men accumulated the clay that was dug locally.

Zuni ceramics are created in the traditional manner of a smoothed coil shape painted with slips and mineral pigments, fired in an open fire. This style of pot is called Kiapa Polychrome, to distinguish it from earlier polychrome jars with low shoulder bulge. The butterfly design, centered within the stepped cloud pattern, is one of the most favored by the Zuni. In the 21st century, there are some male potters and electric kilns are sometimes used.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 2: 3.studio 17-18; Explorations in Art Grade 3: 6.35; Explorations in Art Grade 4: 4.studio 23-24; Explorations in Art Grade 6: 4.22; A Community Connection: 2.6, 5.2; The Visual Experience: 10.6, 14.5; Discovering Art History: 4.10

Happening in Western Art History: Neoclassicism

Yet another renewal of the aesthetic traditions of ancient Greece and Rome was pumped up after the discovery of Pompeii in 1748. This discovery and excavation coincided with the period known as the Enlightenment, which studied classical ideas of philosophy, science, democracy, and education. It also coincided with the democratic revolutions in the US and France, which made earnest attempts at modeling their new societies on the ancient Greek democracies. Unfortunately, “new classicism” had more impact on the arts than it did on government. We are all familiar with the “biggies” of Neoclassicism (David, Ingres, etc), but there are many interesting artists who quietly pursued the style, and not for political reasons outside of the two major “hubs” of the style, Paris and Rome.

|

| Jean-Victor Bertin (1767–1842,France), An Aqueduct Near a Fortress, 1807. Oil on canvas, 14 1/16" x 16 1/16" (35.8 x 40.8 cm). ©Cleveland Museum of Art. (CL-326) |

Jean-Victor Bertin originally studied history painting in Paris, then considered the most illustrious category of subject matter. He abandoned it as stifling and became interested in landscape painting, near the bottom on the list of subject categories considered the most venerable. Studying under a neoclassical artist, he helped devise the category of “historic landscape,” which would incorporate neoclassical ideas into the landscape category to beef up its appeal at the French Academy.

One of Bertin’s contributions to art was his interest in painting outdoors, en plein air as the Impressionists did, at least sixty years before them. He began this practice on a visit to Rome between 1806 and 1808. Painting outdoors was long a practice among Italian artists interested in landscape painting. Bertin used the method to achieve accurate images for his studio paintings on classical subjects.

Bertin’s painting is firmly in the neoclassical style with the smooth brushwork, serene atmosphere, dignified monumentality, and classical/mythological allusions. One of Bertin’s most renowned students, Camille Corot (1796–1875), painted a similar subject en plein air (of the Claudian Aqueduct of ca. 38–52 CE) when in Italy as Bertin’s student in 1825-1828, although it is more a study of morning light than an ode to classicism.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 1: 4.21; Explorations in Art Grade 2: 1.4; Explorations in Art Grade 4: 3.13, 4.24; Explorations in Art Grade 5: 4.19; Explorations in Art Grade 6: 2.7; A Community Connection: 6.2; A Global Pursuit: 6.4; Experience Painting: 6; Exploring Painting: 11; The Visual Experience: 9.3, 16.3; Discovering Art History: 12.1

|

| Nast Porcelain Factory (firm Paris, 1783–1835), Dinner plate from a dinner and dessert service, from a service for James Madison, 1806. Hard-paste porcelain with enamel and gold leaf decoration, width: 11 3/8" (28.9 cm).© Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-3394) |

Artists of the miscellaneous arts were naturally receptive to the neoclassical style because of the abundant number of decorative motifs available from classical antiquity. This dinner plate bears a popular group of motifs on Nast wares, the shield-like medallion between scrollwork and stylized palm fronds (“palmette”). Such motifs occur on ancient Greek vase paintings from the earliest times, as well as been visible as reliefs on Roman architecture. The restrained use of decoration in contrast with the simple white plate is typical of Neoclassicism.

The Nast factory in Paris provided ceramics for wealthy French families and noble families and rulers throughout Europe from the height of Neoclassicism to its waning days in France in the 1830s. This dinner service was a special order by James Madison as a private citizen, but was used by him when he was president. The service was removed from the White House safely in 1814 when the British burned the executive mansion during the War of 1812. Elements of the service are still located in the China Room of the White House.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art 2 3.studio 17-18; Explorations in Art 3 6.35; A Community Connection 2.6, 5.2; A Personal Journey 3.4; A Global Pursuit 6.4; Experience Clay 4; Exploring Visual Design 7; Discovering Art History 12.1; The Visual Experience 10.6, 16.3

|

| William Blake (1757–1827,Britain), Mary Magdalen Washing Christ’s Feet, from a series on The Life of Christ, ca. 1805. Ink and watercolor on paper, 13 3/4" x 13 5/8" (34.9 x 34.6 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-1704) |

While Neoclassicism had enthusiastic appeal in British art, promulgated by the Royal Academy in London and such academic artists as Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792), there was a strong current of Romanticism in Britain at the same time. In the work of some artists, the two strains merged in their work.

In Britain, some artists affected by the Neoclassical style, studying it through the lens of Italian Renaissance and Baroque art, were influenced strongly by Renaissance interpretations of the Neoclassical ideas, rather than purely copying Greek and Roman art. William Blake was influenced by the dramatic aspect of Michelangelo’s (1475–1564) work. Trained as an engraver, he briefly studied at the Royal Academy but rejected Reynold’s admonition that the purist form of art was Neoclassicism. Rejecting the Neoclassical idea that rules should govern creativity, his art was a lifelong expression of unencumbered imagination.

This print is a fascinating combination of Romanticism in the dramatically sloping, non-linear perspective, the dramatic lighting, open composition and fluidly elongated figures, and Neoclassicism in the attention to details such as costume, Roman customs of eating, antique vessels and patterns, and classically stylized profile views of faces. The Michelangelo influence of emphasizing the human body under the garments is evident.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 2: 4.19; Explorations in Art Grade 3: 1.3, 3.3.studio 17-18; Explorations in Art Grade 4: 1.2, Explorations in Art Grade 6: 1.1, 1.3, 3.16; A Personal Journey: 1.3; A Community Connection: 6.2; A Global Pursuit: 6.4; Experience Painting: 4; Exploring Painting: 5, 10; The Visual Experience: 9.2, 16.3, 16.4; Discovering Art History: 12.1, 12

Comments