African American History Month 2017 #3

Today’s artist to mark the fortieth anniversary of the exhibit Two Centuries of Black Art is Jacob Lawrence. His style is truly one of the most unique, personal styles to come out of the Harlem Renaissance period, during which he grew up in New York. I’ve read it variously designated “Social Realism” or “Expressionism,” neither of which I think are a precise fit. Going against the art historian grain, I feel it is too sophisticated of a style to categorize!

|

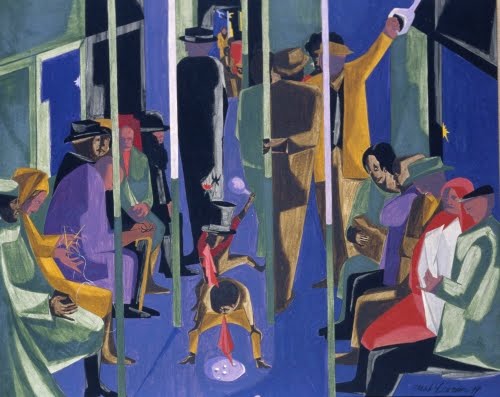

| Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), Subway Acrobats, 1959. Tempera on paper, 11 13/16" x 24" (30 x 61 cm). Private Collection. Image courtesy Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1976. © 2017 Estate of Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (8S-21940lwars) |

Lawrence was born in Atlantic City, New Jersey, but moved to Harlem when he was twelve years old. His mother enrolled him in after school art programs where he discovered a love of drawing and painting. His earliest drawings were crayon and color pencil copies of the patterns he saw in rugs from the Middle East, which he filled in with color. Lawrence subsequently used this technique in his painting all his life.

Lawrence began painting scenes of life in Harlem in the 1930s. Meeting other artists of the Harlem Renaissance, he learned to appreciate the importance of promoting African American culture and its unique place in American history through art. He made a name for himself for the first time in 1939 when he exhibited his series of panels on the life of Haitian general Toussaint l’Overture. The famous Migration of the Negro series followed to critical acclaim. Throughout his life he depicted the life of African Americans in all its facets in New York, including in the subway.

His style varied little through his career except to become a more sophisticated, involved process. He applied one color at a time to the whole work, in that way providing uniformity of color balance. The technique also enhanced the pattern and lively surface. It was equally as effective in silkscreen prints as in painting.

Tomorrow I will feature Edward Mitchell Bannister and his work from Two Centuries of Black Art.

Other posts in this series:

Comments