African American History Month: Dindga McCannon

Today my series celebrating African American (Art) History Month 2020 continues with another artist who was part of groundbreaking African American artist collectives: Dindga McCannon.

|

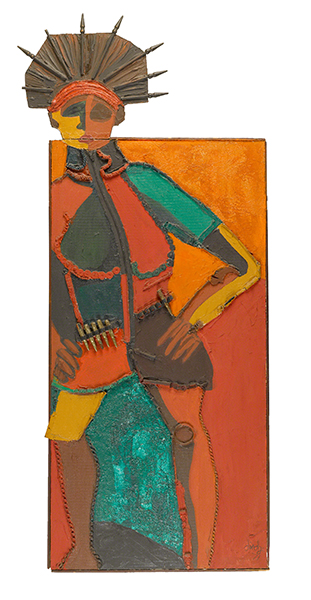

| Dindga McCannon (born 1947, United States), Revolutionary Sister, 1971. Nails, plastic, fabric, and acrylic on wood construction, 62" x 27" (157.5 x 68.6 cm). Brooklyn Museum. © 2020 Dindga McCannon. (BMA-4839) |

The goals of the group Spiral—which I discussed on Monday—for African American artists were ambitious, however the original group only included one African American woman, Emma Amos (born 1938). The nascent Feminist Artist movement of the early 1970s has rightly been pointed out to have been primarily a “middle-class white woman’s movement.” African American women artists had the double whammy of being Black and female. McCannon became active in the formation of African American women artists’ groups in the 1970s.

McCannon was born and raised in Harlem. She chose not to study art in college, preferring to learn her craft independently. She learned printmaking in Robert Blackburn’s (1920–2003) Printmaking Workshop (open 1948–2001). Blackburn, an African American printmaker, envisioned a community-oriented free lithography press, where artists such as Romare Bearden (1911–1988) and Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000) honed their printmaking skills in the 1950s. McCannon painted privately with Richard Mayhew (born 1924/1934) and Charles Alston (1907–1977).

As a teenager in the late 1960s, McCannon belonged to Weusi, a “Black aesthetic” artists’ collective in Harlem, a group that was almost all male. She wanted a connection with other women artists. The ferment of the Feminist movement helped her find groups where race and gender intersected in the 1970s. This included Just Above Midtown, a non-profit artist group for both males and females founded in 1974, the Artists in Residence cooperative gallery founded in 1972, and Heresies magazine (1977–1993), a feminist magazine that featured minority and women artists on a monthly basis.

McCannon was a founding member of the group Where We At, Black Women Artists, Inc. (WWA) in 1971. This group of Black feminist artists seeking to empower their voices in the “official (white) art world” included Faith Ringgold (born 1930), and met in McCannon’s Brooklyn home. Revolutionary Sister, of the same year the group was formed, reflects the socio-political concerns with which Black women artist groups wrestled, while at the same time trying to get their foot in the door of the white-controlled gallery world.

As McCannon stated, in the 1970s there were not many “women warriors” for Black women to look up to, so she created one in Revolutionary Sister. The piece shows her unique blending of art disciplines—sewing, painting, and found object assemblage—that has become the hallmark of her career. It contains objects bought in a hardware store, another place, according to McCannon, women were not welcome at the time. It contains the red/green/black color scheme that eventually became the colors of the Black Empowerment movement: red for the blood shed by Blacks as slaves, green for mother Africa, and black for the people.

The series continues Friday with a post about Howardena Pindell and her exploration of deconstruction and reconstruction in works on paper.

Comments