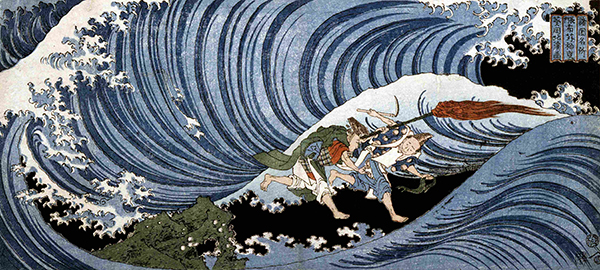

Happy New Year 2023: Totoya Hokkei

Mekari Shinji at the Mekari Shrine in Japan is an annual ritual of cutting wakame seaweed—symbolizing wealth and good fortune—from the ocean at low tide on New Year’s day of the old lunar calendar. The seaweed is then offered on the altar for luck and prosperity in the year ahead. The ritual was designated an Intangible Folk Cultural Asset by Fukuoka Prefecture. Two Shinto priests wearing ceremonial robes and headwear are led to the ocean by a third priest carrying a three-meter-long torch to harvest the wakame from the tops of rocks.

|

| Totoya Hokkei (1780–1850, Japan), Shinto Ceremony at the Mekari Shrine, Nagato Province, from the series Famous Places in Various Provinces, ca. 1830. Color woodblock print on paper, 6 ¾" x 14 7/8" (17.1 x 37.8 cm). © 2022 Worcester Art Museum (WAM-294) |

The stylized rendition of the wave in this print by Totoya Hokkei depicting Mekari Shinji is similar to the waves rendered by the great landscape master Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), right down to the parallel lines that form the waves. The stylization of waves ultimately was borrowed by print artists from the representation of water in the yamato-e (traditional Japanese) style of landscape, usually screen paintings. There are good examples of such wave paintings in the work of Ogata Kōrin (1658–1715), particularly Rough Waves at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

The Edo Period (1615–1868) in Japan was the last period characterized predominantly by traditional Japanese culture. The Tokugawa military dictators (shogun), who closed Japan to both Eastern and Western powers, clamped down on samurai (military) families with harsh taxation, enacted sumptuary laws (controlling what people could wear and own), and censored art and the press. For some 250 years, Japan experienced a period of unequaled peace and prosperity. The middle class prospered in providing services to the upper classes without having to compete with foreign imports. Japanese cities flourished, establishing entertainment districts—Yoshiwara in Edo, Shimabara in Kyoto, and Shinmachi in Osaka—that contained theaters, restaurants, tea houses, print shops, and brothels. The Tokugawa established these districts as a distraction for the newly prosperous townspeople to keep them out of political intrigue.

In the arts, printmaking flourished with traditional subjects and styles. Color woodblock printmaking experienced sophisticated development, as artists churned out prints documenting the pleasures of city life. Prints were affordable to middle class patrons, more so than painting. The style of the woodblock prints during the Edo Period was called ukiyo-e or “pictures of the floating world.” In this instance, “floating” referred to the transience of worldly pleasures.

The great tradition of Japanese landscape painting did not translate into the woodblock ukiyo-e style until the late 1700s. Woodblock prints of landscapes—like those of beautiful women and Kabuki actors—were aimed at a middle-class audience uneducated in the lofty aesthetic ideals of traditional Japanese and Chinese painting. They were naturalistic and represented places and views popular among the mobile middle class.

Hokkei (family name Totoya) was one of Hokusai’s best students. He had initially studied landscape painting with the noble Kanō School, but eventually became one of Hokusai’s first pupils. Hokkei made his ukiyo-e debut with illustrations for comic novels around 1800. He continued to produce prints of everyday life, but preferred landscape more and more, particularly after Hokusai published his famous Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series in 1836. While impelled to produce landscapes, Hokkei’s style was quite different from the master.

Comments