Utilitarian Object or Sculpture?

First of all, let me clarify the use of “utilitarian” or “decorative arts.” These are unfortunately terms art historians are stuck with from the 1800s art history gods in Western Europe. I personally look at a beautifully presented meal as the work of an artist, so, let’s go from there.

Anyway, sometimes, when entering new images into our digital collection, I really have to stop and think about how to categorize an object. Last week’s blog that showed furniture in which the sculptural element almost overruled the utilitarian aspect of the piece got me thinking (oh-oh). Now, I wouldn’t normally consider, say, a vacuum cleaner fine art. It seems, though, in the 21st century, that designers of utilitarian objects have that in mind for a whole variety of products. And then, when one thinks about it (oh-oh), one realizes that this has always been the impulse of designers/artists! Here are some examples I picked to give you a moment to mull over my question: Is it utilitarian or sculpture, or both?

|

| Ancient Egypt, Head of the Coffin of Horankh, ca. 700 BCE. Gessoed and painted wood, with obsidian, calcite and bronze inlay, near life-sized. © Dallas Museum of Art. (DMA-59A) |

Nearly all of the arts in ancient Egypt had some relation to their religion and their belief in the afterlife being a continuation of earthly life. To that end, their tombs were filled with objects that contained likenesses of themselves, many meant to capture the ka after it left the mummified body if it got temporarily lost on its way to the afterlife. Before the Ptolemaic period, it was customary for wealthy Egyptians to have elaborate carved, painted, and inlaid coffins. Yes, a coffin is a utilitarian object, I guess (though you only use it once), but, I don’t have the “coffin” category of decorative arts. So, this beautifully carved and painted, idealized coffin lid goes under “sculpture.”

|

| Ancient Peru, Moche Culture, Effigy vessel, 400-600 CE. Painted earthenware, 12 15/16" x 8 1/4" x 7" (33 x 21 x 18 cm). © Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. (MFH-628) |

While the Moche culture of Peru also believed in an afterlife as a richer version of earthly life, the purpose of the many types of effigy vessels (animal, deity, human head) is still not clear to scholars. Many have been found in burials, and it is thought that is because they were considered objects of status. This is perhaps borne out by the fact that equally large numbers of effigy vessels have been excavated from family compounds. I know it is thought that these vessels were mold made, but, I saw dozens of these portrait jars in April in an exhibition on the Moche, and there were no two alike. Some of them are compellingly realistic, even down to showing faces that had been disfigured by the sandfly-borne, flesh-eating disease leishmaniasis. I categorize these as “ceramics,” but in my mind this genre of object is sculpture!

|

| France, Potpourri Vase, ca. 1890, copy of 1757 original from Sèvres Porcelain Factory. Hard-paste porcelain, enamel painted and gilt, 15" x 14 1/4" x 9" (38.1 x 36.2 x 22.9 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-1120) |

Why would anyone copy an example of overly decorated froufrou from the Rococo period (ca. 1700-1730s)? It just conjures up images of conspicuous consumption, noblesse oblige, and, dare I say it, a lack of taste? But, the Rococo Revival was big from the mid-1800s to the 1890s, so here we have this gem. It’s ironic that a style that really only flourished after the death of Louix XIV (1715) to around the time of the discovery of the ruins of Pompeii (1748) was so lavishly revived in the mid-1800s! I appreciate the use of this genre of vase, a step up from the bowl of potpourri on a coffee table. But subtlety is not the hallmark of the Rococo style. I stuck this in because so many Rococo objects were so over the top in three-dimensional form (arabesques, volutes, etc) that they could easily stand on the mantle as an odd knick knack that needs constant dusting. That said, I still categorize this as “ceramic.”

|

| Baule People, Ivory Coast, Leopard Stool (royal seat), from Toumodi, 1900s. Painted wood, 17 11/16" x 8 5/8" x 33" (45 x 22 x 84 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-2721) |

The leopard is a symbol of ruling status throughout the arts of sub-Saharan African cultures. I know that royal seats such as this were reserved for one person, and it wasn’t exactly a chair in the living room to sit on and watch TV. However, did you ever look at a piece of furniture and think it’s just too beautiful to be actually used? Additionally, considering the reserved purpose of this seat, we can see why such special attention is paid to its form. The jaguar with prey in its mouth is an obvious symbol of the ruler’s power over detractors. On top of the leopard is an akan stool that is typical status symbol of rulers of the Asante of neighboring Ghana. The combination of these two symbols is powerful, so, even though I do catalog this as “furniture” (only because of its title), once again, in my mind I’m thinking “sculpture!”

|

| Iatmul People, Papua New Guinea, Suspension Hook, from Sepik River area, Village of Aibom, 1900s. Wood, fiber, shell and pigment, 35 15/16" x 10 15/16" x 6" (91.44 x 27.9 x 15.2 cm). © MFA, Boston. (MFAB-738) |

In many Oceanic cultures, sculpture, painting, or carving adorns almost every object of everyday and ritual life. By decorating all objects in their lives, the people of these cultures believe that they can bring the world of the spirits into active participation in everyday life. Like many of the other peoples of the Sepik River region, the Iatmul carve (often elaborate) basket hooks, also called suspension hooks. Figurative hooks suspended from the rafters of ordinary dwellings and lavishly decorated men's cult houses have multiple purposes and meanings. Ordinarily, they were used to hang bags and vessels of food out of reach of dogs, children, etc. More elaborate examples, such as this impressive piece, had religious significance and served to suspend skull trophies. The human forms on the upright shanks may represent ancestors and refer to family and clan myths, assuring the welfare of their community. Since I don’t have a “hook” designation in my database, I’m calling this “sculpture!” It’s also a nice example of the painting style.

|

| Alexander Calder (1898–1976, US), Comb, before 1943. Hammered brass, 6 1/2" x 3 13/16" x 3/4" (16.5 x 9.8 x 1.9 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2015 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (MOMA-D0771caars) |

Everyone knows that Calder was a pioneer of kinetic sculpture in his mobiles and stabiles. Many probably also know that he also designed ceramic tile murals, tapestries, carpets, and explored painting. And I’m pretty sure not everyone knows that he designed jewelry as well. If I still had long hair, I’d love to wear this exquisite comb. It’s so modern, timeless, and yet it puts one in mind of the ancient Aegean cultures. I do catalog this as “jewelry,” but it sure makes a beautiful little sculptural form.

|

| Philippe Starck (born 1949, France), Walter Wayle Wall Clock, 1989. Thermoplastic resin, 10" x 10" x 2" (25.4 x 25.4 x 5.1 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2015 Philippe Starck. (MOMA-D0592) |

I’m not sure how many wonderful historical sources Starck has used in his many fabulous designs. All I know is that sitting at the bar in the Royalton Hotel in New York is like being in a cross between a 1930s film-noir and the bar scene from a Star Wars movie. His designs for everyday objects are so spectacular and inventive, it’s hard to decide which genre I like the best, though, I must say, this clock design is right up at the top of my list. I like Starck’s designs for home objects because he really brings a sculptural aesthetic into utilitarian design. This clock is such an interesting idea. For one thing I like the flipper hands, and the free-form lack of face or numbers flies in the face of the conventional idea of a clock being some strict regulating instrument. If I didn’t know it was a clock, I might think “sculpture” in the spirit of the biomorphic forms of Jean Arp (1886–1966).

|

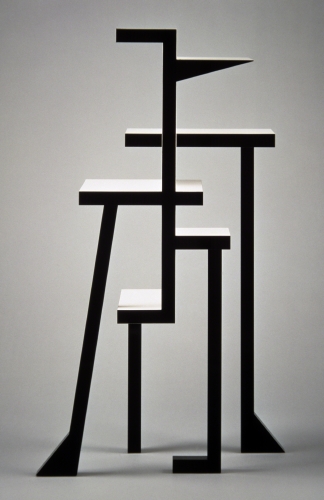

| Okayama Sinya (born 1941, Japan), Kotobuki Shelves, 1989. Lacquered wood, 74 3/8" x 35 3/8" x 15 3/4" (189 x 90 x 40 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art. © 2015 Okayama Sinya. (PMA-2659) |

寿

Okayama is one of the pioneers of postmodern aesthetic in Japanese design, starting in the late 1970s. After working in the design department of a department store chain, he produced the first furniture and lighting fixtures under his own name in 1981. Many of Okayama’s designs suggest the object, object type, or word for which they are named. Other objects relate directly to their names, such as this shelving unit that is designed in the shape of the Japanese ideogram for the word “longevity” or “congratulations.” I’ve included the Kanji or the word, and I can totally see how the shelves relate to it. As much as I would love to consider this unique concept “sculpture,” I’m afraid I’ve cataloged it as “furniture.”

|

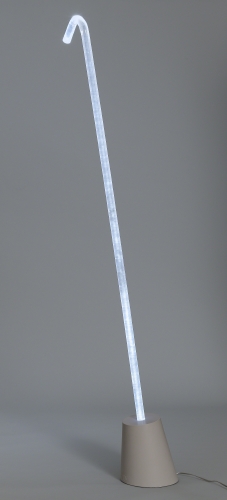

| Paul Cocksedge (born 1978, Britain), Pole Light, 2008. Acrylic, LEDs, and concrete base, 68 13/16" x 7 7/8" (174.9 x 20 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2015 Paul Cocksedge. (MOMA-D1212) |

This has to be one of my “favorite new things.” I could just see this lamp in so many places in an apartment (well, maybe not on my drawing board or over my easel). It’s so elegant and yet apparently functional, although I’m not sure how bright the light gets. Even if it is a soft glow, this would be a really neat lighted sculpture to have in a dark room. According to their website, “The Paul Cocksedge Studio, founded in 2004 in London, is a design studio that emphasizes innovative design supported by research into the limits of technology, materials and manufacturing processes.” I think it’s really interesting that they design everyday objects with a long side eye to what must be a conventional wisdom about lamp design, in favor of an aesthetic.

Correlations to Davis Programs: Explorations in Art Grade 1: 6.35; Explorations in Art Grade 2: 6.35-36 studio; Explorations in Art Grade 3: 6.35, 6.35-36 studio, 6.Connections; Explorations in Art Grade 6: 4.23-24 studio; A Community Connection: 5.2, 2.6; A Personal Journey: 3.1, 3.4; A Global Pursuit: 5.6; The Visual Experience: 10.6, 12.4; Discovering Art History: 2.2

Comments