To Mask or Not to Mask

The word “mask” gets an emotional response from some folks in these days of pandemic. I wonder, if the masks we're asked to wear looked like these following examples from Davis Digital’s image collection, would we enjoy the task more? Probably not, but here are some beautiful examples of the genre from around the globe.

|

| Calima Culture, Colombia, Ceremonial Mask, ca. 500 CE. Gold, 7 ¼" x 9 7/8" x 1 ¼" (18.4 x 25.1 x 3.2 cm). © 2021 Dallas Art Museum. (DAM-25) |

Calima refers to a group of cultures that flourished in the Valley del Cauca: the Ilama, the Yotoco, the Sonso, and the Malagana. While metallurgy was known to all of these cultures, it is believed that the Yotoco developed the form of hammered gold works of art. The Calima cultures also excelled in ceramic arts and large-scale sculpture.

Gold was believed to be a product of the sun, the supreme creator, and had special associations with fertility, protection, and power. For the people of Colombia, the value of gold lay in the symbolic and transformative properties associated with its color, aura, and malleability. It was the glittering surface of the substance that mattered, not the substance itself.

Gold was used to engage with animal spirits, music, dance, and sunlight. Likewise, gold objects were often incorporated in rituals. Because mostly the elite of these societies took part in these rituals, gold achieved status in that way. Masks such as this were funerary, buried with the deceased as protection and an indication of the person's status in the afterlife.

|

| Senufo People, Mali, Kponyungo Mask, from Vallée du Bandama region, or Sikasso region, late 1900s. Painted wood, 14 3/16" x 13" x 33 7/16" (36 x 33 x 85 cm). © 2021 Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-5607) |

The Senufo people (also called Siena and Sene) are an ethnic group living in Ivory Coast, Mali, and Burkina Faso. Many of them live in the Middle Volta valley between the Bagoé, Bani, and Mouhoun Rivers in West Africa. Senufo ancestry is not fully known, but they are believed to have migrated northward from the area around Odienné in Ivory Coast. They are now known in distinctly northern, central, and southern Senufo groups. They have traditionally worshipped ancestors and earth spirits, but many have converted to Islam since the 1700s.

A broad translation of Kponyungo is "funeral head mask.” The Senufo consist of numerous diverse subgroups and recognize three secret societies—the Poro, Sandogo, and Wambele. These societies serve the purpose of instructing young men and women how to be good community members, honor their elders and ancestors, and respect supernatural forces.

The Poro society makes specialized masks that are used to connect with the gods, ancestors, and bush spirits. The Kponyungo, also known as Firespitter (sort of like a dragon?), is the most well-known Senufo mask. Members of the Poro society, a “secret men’s society,” wear it during the funeral ceremonies of their deceased members to honor them as well as well as ward off evil spirits. Each Poro organization present at the funeral is represented by a member wearing the Kponyungo mask.

|

| Ancient Rome, Tragic Mask, from Italy, probably first century CE. Terra cotta, 7 ¼" x 6" (18.4 x 15.3 cm). © 2021 The Cleveland Museum of Art. (CL-1077) |

After Rome finished its conquest of Greece with the defeat of Corinth in 146 BCE, the influence of Greek art on Rome was not limited to the importation of Greek artists. As early as 212 BCE, when the Romans sacked the Greek trading city of Syracuse, Greek art began to pour into Rome, decorating public buildings and the homes of rulers and the wealthy. Romans became insatiable in their appreciation of all areas of Greek culture, including the theater. Greek plays were the most often performed works.

The Romans inherited the custom of masked actors from the Greeks. This was a necessary art form because in Greek and Roman theaters, usually built on the side of a hill, there was a great distance between the audience and the performers.

Masks conveyed character by exaggerating features male or female, comic or tragic, like this one. The mask covered the actor's head and not only amplified the facial features so that the audience could identify their role, but they were also fashioned to amplify the performer's voice.

Masks allowed Roman actors to perform multiple different roles, personalized to each character. Male masks were painted with brown skin, female roles with white skin. They were made from a variety of materials, from linen or cork to wood or even bronze.

|

| Kwakwaka'wakw Culture, British Columbia, Canada, Baleen Whale Mask, from Knight’s Inlet, 1800s. Cedar wood, hide, cotton, cord, nails, pigment, 23 5/8" x 28 ½" x 6' 9" (60 x 72.4 x 206 cm). © 2021 Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-4853) |

Kwakwaka'wakw was derived from Kwagu'l, a single community of the Kwakwaka'wakw near Fort Rupert. Kwak'wala is the language of these related clans. Kwakwaka’wakw means "Kwak'wala speaking people." Oral history of the culture attributes the origin of Kwakwaka’wakw ancestors to animals who discarded their animal forms to be humans when they arrived at a given spot. Animals from these origin traditions include the thunderbird, seagull, orca (whale), and grizzly bear. Ancestors who had human origins are thought to have come from other distant places. Traditionally, the Kwakwaka’wakw were organized into thirty independent clans on northern Vancouver Island and adjacent mainland British Columbia around Alert Bay.

Masks like this are owned by an individual (or chief) who has inherited the rights to make, wear, and perform with it during potlatch ceremonies, elaborate communal celebrations. The dancer who wore this mask would identify the orca as a clan animal. The mask is worn along the dancer’s back while he imitates the swimming and diving of the whale by manipulating cords to move the flippers, tail, and jaw. The performance celebrates the connection the Northwest Coast First Nations people have with the whales and bounty of the sea. There are various traditions involving the orcas’ interaction with human beings.

|

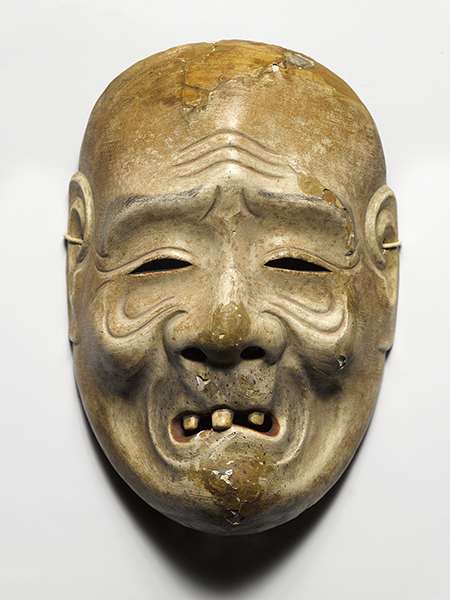

| Japan, Noh Theater Beggar Mask, 1600s–1800s. Wood, lacquer, 8 3/8" x 5 7/8" (21.3 x 14.9 cm). © 2021 Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-5419) |

During the Nara period (645–794 CE) in Japan, a form of popular entertainment called sangaku was imported from China. Sangaku evolved into sarugaku—which consisted of pantomime, acrobatics, and magic for everyday people—and gagaku, a more solemn, narrative form of dance and music that became the exclusive entertainment for the imperial court nobility during festivals and ceremonies. Gagaku was high drama, characterized by highly symbolic gestures, movements, and very little dialogue.

Over time sarugaku and gagaku merged with shirabyōshi (traditional dances performed by women at the imperial court) and dengaku, regional performances celebrated during rice planting. Between the Heian (794–1185) and Kamakura periods (1185–1333), Noh theater achieved its initial form. Noh means "skill or talent" in relation to acting. It was perfected into its present form during the Muromachi period (1392–1573). One of the oldest schools of Noh performers are believed to have descended from the developer of gigaku, a masked drama-dance introduced into Japan in the 600s CE from Korea. Like gagaku, Noh remained the province of the nobles and imperial court. Contemporary Noh is performed for all people.

Noh masks originated from the gigaku between the Heian and Kamakura periods. Realistically carved, these masks are based on the Tang (Chinese) concept of ideal beauty, taking their rounded shape from sculptures of Buddha. The subtlety of carving is matched by the subtlety of tone, gesture, and inflection of the actor. Noh masks are generally carved from a single piece of wood and colored with natural pigments.

This mask represents the tragic character Kagekiyo. It represents a deranged person, once a great soldier who was defeated and exiled. Imprisoned, he lost his sight and allowed himself to starve to death.

|

| Papua New Guinea, New Ireland Province, Malagan Mask, late 1800s/early 1900s. Wood, fiber, bark, pigment, lime, and shell, 12 11/16" x 6" x 14 3/8" (32.3 x 15.2 x 36.5 cm). © 2021 Menil Collection, Houston, TX. (MEN-11) |

New Ireland is in the Bismarck Archipelago, located north of New Guinea. Today it is a province of Papua New Guinea. Art of New Ireland has traditionally centered on malagan, ceremonies and feasts to honor the dead. Performances, feasts, and dances were organized after the funeral, when artists were hired to carve masks and complex sculptures that usually incorporated multiple figures.

The purpose of the malagan ceremonies was to help send the soul of the deceased to the realm of the departed. While the sculptures are not portraits of the deceased, they represented the soul, and are thought to have contained the deceased's soul during the ceremony.

This funerary mask is called tatanua after the dance for which it is used. The dance is performed by pairs or groups of dancers. The mask is meant to honor the deceased, ward off malevolent intentions, and sever the deceased from possessions in the physical world. The feather part of the mask imitates the hairstyle worn by young men for malagan ceremonies, in which the head was partly shaved and the hair was stiffened with lime. All artwork created for the malagan was to honor specific deceased persons. After the ceremonies, the sculptures were usually destroyed. Only masks and musical instruments created for the ceremony were preserved.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art 2E Grade 1: 5.9; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 4: 5.8, 5.9; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 6: 3.9; A Community Connection 2E: 7.6; A Personal Journey 2E: 7.6

Comments