The Month of Frost: Hashimoto Gahō

It’s the last day of November 2020. In Japan, the historical (traditional) calendar was based on the Chinese lunar calendar, which meant that months began three to seven weeks later than the Gregorian calendar. As a result, Japanese artist birthdays are approximations in Western dating. The eleventh month is now called just that: juichigatsu, “eleventh” plus gatsu (“month”). Historically, November in Japan would have carried over into December’s spot on the Western calendar. The traditional name was Shimotsuki, which means “frost moon.” It was also called the “month of frost.” Whether November (traditionally) or December, this beautiful six-fold screen is a preview of coming seasonal attractions.

|

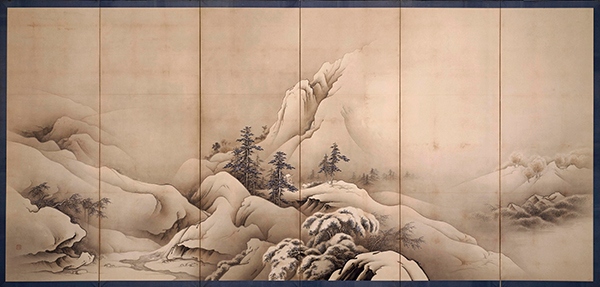

| Hashimoto Gahō (1835–1930, Japan), Snowy Landscape, mid-1880s. Ink, light color on paper mounted on wooden frame as a six-fold screen, 5' 6" x 11' 8" (169.2 x 361.4 cm). © 2020 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (MFAB-926) |

Hashimoto Gahō painted in both the Kanō School yamato-e style of decorative colors and gold leaf backgrounds and in the monochromatic ink style of Nihon-ga. While Hashimoto emphasized traditional subjects and techniques, he also incorporated certain elements of Western art.

Snow scenes were one of Hashimoto’s specialties. Snowy Landscape is presented as a traditional byobu (six-fold screen), meant to partition rooms. The Japanese landscape tradition of suggesting depth by using mist is augmented with Western-influenced heightened realism, particularly in the subtle nuances of wash used to suggest sculptural form.

The isolationist Tokugawa Shogunate (1615–1868)—called the Edo Period after the Tokugawa capital, present-day Tokyo—prohibited the Japanese from contact with any foreign countries other than tenuous relations with China and Korea. Painting during the period was greatly influenced by historic styles, particularly from the Heian Period (794–1185).

After the forced opening of Japanese ports by American warships in 1853, Western art was accessible for the first time in almost 250 years and had a major impact on Japanese art. Western art was particularly influential on painting and printmaking.

During the Meiji "restoration" (1868–1912), when the shogunate was abolished and power supposedly returned to the emperor, many artists studied Western art in earnest, some of them traveling to Europe. The influence of Western art had notable results. Some artists adapted completely Westernized styles, including Western materials such as oil paint and canvas and Western subjects. Other artists adapted certain Western stylistic features such as perspective, chiaroscuro, and more plastic form.

Many Japanese artists, however, refused to allow Western influence to affect their art. The art of traditionalists was called Nihon-ga, or “Japanese style painting.” The art of those influenced by Western art, whether a little bit or wholeheartedly, was called yo-ga, or "Western style painting." The adherents of Nihon-ga insisted on traditional subject matter as well as traditional techniques, such as the monochromatic style of painting.

Hashimoto was a major proponent of the Nihon-ga strain of Meiji painting who established his own studio by 1860. He was born in Edo and initially trained by his father, the Kanō School-influenced Hashimoto Osakuni, the official Kanō school painter for a samurai family in Kawagoe. When he was 12 years old, Hashimoto became a pupil of Kanō Shosen'in Tadanobu (1823–1880). His fellow pupil and friend Kanō Hōgai (1828–1888) would also be one of the pioneers of the Nihon-ga style.

Correlations to Davis programs: A Community Connection 2E: 4.5; A Personal Journey 2E: 5.4; A Global Pursuit 2E: 7.5; Exploring Painting 3E: Chapter 11; Discovering Art History 4E: 4.4; The Visual Experience 3E: 13.5; The Visual Experience 4E: 8.13

Comments