Sumidagawa in July: Japanese Woodcuts

The actual festival of Sumidagawa (“Sumida River”) occurs in Tokyo in the last week of August, but there are fireworks in Tokyo from May through August, starting with the Opening of the Sumida River in May. Now, I’ve tried doing multiple block color woodcuts, and let me tell you, they are a challenge.

What has ALWAYS impressed me about the color woodcuts in Japanese art is that, no matter how many colors, the registration is right on the mark! So, you might imagine how impressed I am at depictions of fireworks! The very ephemeral nature of fireworks makes them a subject I wouldn’t even try duplicating in oils, much less as a woodcut. So here are some great examples of different approaches to fireworks in woodcut prints.

|

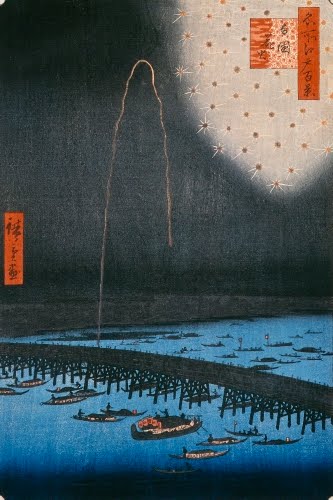

| Utagawa Hiroshige I (1797–1858, Japan), Fireworks at Ryogoku (bridge), #98 from the One Hundred Famous Views of Edos eries,1858. Color woodcut print on paper, 14 3/16" x 9 7/16" (36 x 24 cm). © 2017 Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-822) |

I’ll take any excuse to include my favorite ukiyo-e artist (because he does landscapes!). Utagawa Hiroshige I was the first artist that I’m aware of to explore the fireworks theme in a woodblock print. I always comment on the awe I feel for the woodblock carvers of Hiroshige’s drawings. Imagine carving the intersecting lines of the Ryogoku Bridge’s posts or that single line of firework flare in the night sky!

Fireworks in Japan were developed in the mid-1500s. Sophisticated, large displays were perfected by 1700. Fireworks as entertainment are said to have been introduced to the Japanese by British traders accompanied by Chinese fireworks merchants in 1613, although there may be earlier examples. Up until the 1700s, fireworks were generally used in festivals to frighten negative spirits.

The Shogun Yoshimune (1716–1751) commissioned fireworks for the first Ryogoku Kawabiraki Fireworks Festival ("opening of the river [Sumida] at Ryogoku [bridge]") for one summer to take people's minds off of a famine and resulting pandemic in western Japan. "Taking in the cool of the river" was a popular pastime from May through September, and eventually these fireworks took place on any clear night in summer. The Sumidagawa Festival is just one of those occasions, but the most popular of the summer. Compared to numerous other depictions of Ryogoku Bridge, the view from this series has removed the human presence to almost nil, in contrast with the dominating—almost melancholy—night sky and dark bridge.

|

| Ogata Gekko (1859-1920, Japan), Woman Looking at Fireworks from a Veranda, from the Women’s Customs and Manners series, 1897. Color woodcut print on paper, 14 1/2" x 10" (36.8 x 25.4 cm). © 2017 Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-2358) |

Comparing this Ogata Gekko print with that of Hiroshige is interesting because they each chose different moments and types of fireworks to illustrate. I can almost contrast in my mind the “pop” happening in Ogata’s print and the multiple “booms” of the Hiroshige; that’s how well these artists convey the sensation of seeing fireworks. I would image the printers of both these works rubbed some of the dark ink around the bright area to create nuances in the night sky. Brilliant! I’m pretty sure this woman is on a veranda overlooking the Sumida River.

Ogata, about whom I’ve written before, was an anomaly when he produced prints because it was after the heyday of the ukiyo-e style. He relentlessly pursued the revival of the genre in his subject matter, preferring close-up views of nature to “bijin-ga”—beautiful women prints. However, the subject of “Customs of Women” was a traditional one in ukiyo-e, made popular by the late 1700s artist Utamaro (1753–1806). Ogata, who was apparently self-taught in the woodcut medium, displays subtle influences of Western art, such as perspective and more realism in his figure treatment.

|

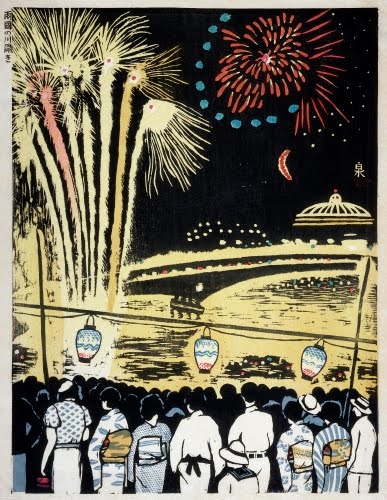

| Kishio Koizumi (1893–1945, Japan), River Opening Ceremony at Ryogoku, from the series One Hundred Views of Tokyo in the Showa Era, 1935/1945. Color woodcut print on paper, 15 5/8" x 12" (39.8 x 30.5 cm). Worcester Art Museum. (WAM-629) |

This Kishio Koizumi print is a most awesome contrast of Hiroshige’s Kawabiraki scene. Kishio’s scene is much flatter, with the major elements reduced to shapes and the space somewhat skewed. The fireworks are abstracted with no nuances in the night sky from the glow of the explosions. Like Hiroshige’s print, however, Kishio manages to capture the essence of the perceived experience by the artist.

Kishio was a major figure in the sosaku hanga (creative print) movement, which sought to infuse the traditional ukiyo-e genre with Western modernist elements, while maintaining traditional subjects. The creative print artists were different from the traditional ukiyo-e artists also, if you remember, because they drew, carved the woodblock, and executed the prints all themselves. This was a great departure from the master-apprentice system of the glory days of ukiyo-e, in which drawing, transferring to woodblock, carving woodblock, and printing of the image were done by different people.

Kishio was born in Shizuoka. His father, a calligrapher, commissioned woodblock-printed manuals, and Kishio learned the woodblock technique from his father’s block-carver. He studied Western-style watercolor at the Japan Watercolor Institute (Nihon Suisaiga-kai) in Tokyo. The three founders of that academy were woodblock printmakers, so they influenced his decision to go in that direction. He was a member of the Creative Artists Association early on and was an activist for their ideas. This print comes from his most famous series, which is a wonderful historical record of Tokyo before the destruction of World War II (1939–1945).

|

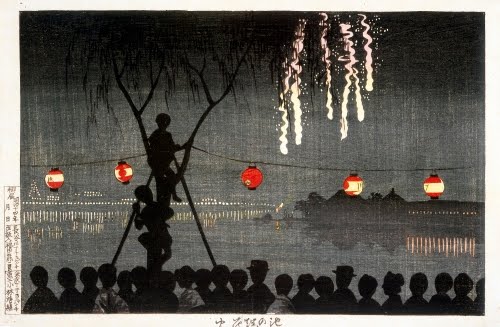

| Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915, Japan), Fireworks at Ikenohata, Shinobazu Pond, 1881. Color woodcut print on paper, 8 5/8" x 13 3/8" (22 x 33.9 cm). © 2017 Worcester Art Museum. (WAM-526) |

The printer has reduced distant forms to mere blocks of color, much as is seen in the backgrounds of Hiroshige’s prints. In the crowd figures, Kobayashi avoids the traditional attention to fine detail of figure in favor of a screen of shapes in silhouette. This sort of simplification resembles what might be seen in the work of European Symbolist painters. He had avidly studied Western art, particularly lithography, and based much of his work on Western etchings and photographs. Kobayashi Kiyochika is often considered the last great ukiyo-e master, even though many of his prints fall under the Meiji Restoration (1868–1912), and the government’s manic quest to modernize Japan as quickly as possible. These fireworks take place near the Shinobazu Pond in Ueno Park in the Taito Ward of Tokyo. I’m not sure what the festival is, but it’s such a great print, combining the influence of Western Impressionism and perspective with traditional Japanese subject matter and technique.

Kobayashi was the son of a minor government official under the last shogunate. After the elimination of the shogunate (1868), he trained himself to be an artist. His first project, which includes this print, was to diligently record scenes of Tokyo as it rapidly became a modernized city. In order to avoid comparison to previous cityscape artists such as Hiroshige, Kobayashi focused on light effects, preferring scenes of dawn, dusk, and night.

Correlations to Davis Programs: Experience Printmaking 4; The Visual Experience 3.5, 13.5; Discovering Art History 2.3, 4.1

Comments