Sōsaku Hanga: Keiko Minami

It never fails to amaze me how certain “facts” in the history of art are true no matter what culture we examine. Fact: up until the early 1900s, certain art forms, subject matter, and styles were not considered “important,” “acceptable,” or even “fine art.”

If we ponder this concept, the first thing that springs into our Western minds is the prejudices of the megalomaniacal, conservative academies of art of Europe and the United States. Not only did those institutions regulate which artists got exhibited and accepted, they also had “standards” on what appropriate media and subject matter could be considered fine art. Oddly enough, when Westerners were first exposed to woodblock prints from Japan, they considered such prints Japanese fine art. In Japan, woodblock prints (I’m talking ukiyo-e style now) were considered an inferior art form suitable only for the lower classes because they were mass-produced.

|

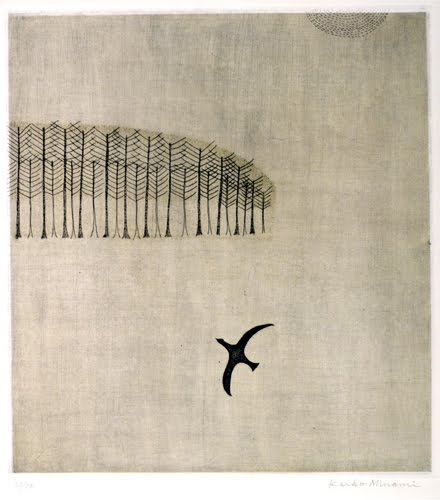

| Keiko Minami (1911–2004, Japan), Taking Flight, 1958. Colored etching, 22 ½" x 15" (57.15 x 38.1 cm). Photo © Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY. (AK-1568) |

Sōsaku hanga (creative print) was a movement that had its origins in Japan as a reaction to the rapid industrialization of the country after its “opening” to Western powers. At the turn of the 20th century, there was a great debate in Japan in artistic and literary circles about expressions of “self.” This was in part influenced by the Japanese exposure to European modernism: many Japanese artists travelled to Europe during the 1890s. Another factor was the reaction by young artists during the first decade of the 1900s to stifling cultural strictures and the establishment in 1907 of the Japan Fine Arts Academy, which looked upon printmaking as a “minor art.” The Creative Print movement artists differed from ukiyo-e artists in that they designed, cut, and printed their works themselves. Traditionally printmaking in Japan consisted of the artist, the woodblock cutter, the printer, and the publisher each contributing to the final print.

Artists of the Creative Print movement primarily considered themselves painters. Many of them emulated modernist movements in the West, and were not broadly accepted among an established art hierarchy that still considered painting the highest of “fine art.” It was only in 1927 that printmaking was accepted by the Japan Fine Arts Academy as art. By that time, however, many Japanese artists were experimenting with modernism. Only after World War II did Japanese modernist prints gain worldwide recognition, thanks in some part to American patronage of works that reflected Western abstraction, a perception of the blending of East and West.

Keiko Minami was a painter and printmaker who went to Paris with her husband Hamaguchi Yozo after World War II. Both were sōsaku hanga artists. Minami’s lyrical, fairy-tale like images were eventually commissioned by UNESCO and UNICEF. This lovely print demonstrates many of the elements and principles of art: line, asymmetrical balance, and positive/negative space. She was primarily interested in young female figures, animals, and nature.

Comments