Happy Birthday Francis Picabia

I always like to celebrate artists who show a wide variety of stylistic exploration. Francis Picabia is certainly one of them.

|

| Francis Picabia (1879–1953), Dances at the Spring, 1912. Oil on canvas, 99 1/8" x 98" (251.8 x 248.9 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (MOMA-P2196piars) |

The child of a French mother and Spanish/Cuban father, Picabia was born on January 22, 1879. As a child, he grew up in a household devoted to the collection of art. He studied at the School of Decorative Arts in Paris in 1895, and later in the studio of painter Fernand Cormon (1845–1924), an academic symbolist/realist. Fellow pupils included future Cubists Georges Braque (1882–1963) and Marie Laurencin (1883–1956). At the time Picabia produced watercolors, but quickly transitioned to oil in an Impressionist style influenced by Camille Pissarro (1830–1903) and Alfred Sisley (1839–1899).

Although the first show of his Impressionist landscapes in 1905 received positive attention, he abandoned what by that time was considered a conventional style, gravitating toward more modernist experimentation, initially Fauvism. By 1912 he had shifted to Cubism, abandoning the representation of nature in favor of expressing memories and personal experiences.

Unlike many of the other artists experimenting with Cubism, Picabia considered the style a good vehicle for conveying personal feelings, rather than sticking to still life and portraiture. Because of the ephemeral nature of memories and experiences, Picabia's Cubism quickly became nonobjective, whereas the other Cubists rarely ventured completely away from recognizable objects.

Dances at the Spring was one of thirteen Cubist paintings Picabia showed at the Salon of the Golden Section, Paris, in 1912. The subject was inspired by the memory of a folk dance Picabia witnessed while on his honeymoon in the Neapolitan countryside in Italy. The artist reduced the figures of two young women dancing to swirling, brilliantly colored planes indicative of their movement and fervor. These colors and disintegration of form go well beyond the Analytical Cubism of Braque and Picasso. Picabia’s reduction of the women's forms to sheet metal-like facets points to another theme that would come to occupy other Cubist painters, that of the machine.

|

| Francis Picabia, M’Amenez-y, 1919–1920. Oil on cardboard, 50 ¾" x 35 7/16" (129 x 90 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (MOMA-P2017piars) |

After World War I (1914–1918), Picabia became fascinated by the idea of industrial and mechanical objects as subject matter. He felt that machines had become part of human life and explored mechanical symbolism. It is believed by art historians (and this is probably purely subjective) that this painting represents acts of human private parts. Personally, I don’t really see it, but Picabia may have taken a page out of Marcel Duchamp’s (1887–1968) playbook in which machines referenced sexuality. It is Picabia’s first experiment with collage.

This painting contains numerous puns that make this work a puzzle to me. There’s “linseed oil” (l’huile de lin), “castor oil” (‘l’huile de ricin), “the artist’s false teeth” (ratelier d’artiste), and “crocodile painting” (peinture crocodile). His interest in machines and automobile parts is supposedly reflected in the title: Take Me There (M’Amenez-y). Picabia reportedly had an obsession with cars, owning 100 of them.

|

| Francis Picabia, Fuel Pump, 1922. Ink and gouache on paper, 30" x 22 1/8" (76.2 x 56.2 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (MOMA-P0107piars) |

Fuel Pump is an obvious reference to a car, although it by no means is an accurate depiction of car parts.

|

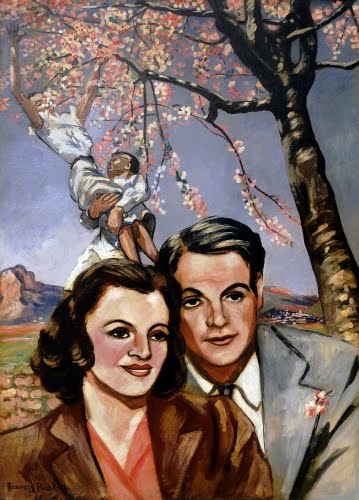

| Francis Picabia, Portrait of a Couple, 1942–1943. Oil on board, 41 5/8" x 30 7/16" (105.7 x 77.4 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (MOMA-P1148plars) |

Although Picabia renounced Dada in 1921, certain ideas of that movement continued in his work. This included the appropriation of found imagery. In one of his last stylistic phases, he appropriated images from magazines and movie posters. The saccharine imagery—executed during the devastation of World War II (1939–1945)—pointedly questions the meaning of art in a world gone wonky. This is exactly the quandary that Dada explored during the aftermath of World War I.

Correlations: Explorations in Art Grade 4: 6.34; Discovering Art History 4E: 14.4; Discovering Art History Digital: 14.4

Comments