Native American Heritage Month: Ledger Art

Little is known of the Arapaho artists who created the drawings in the Henderson Ledger, referred to as Henderson Ledger Artists. The ledger was owned by Frank Henderson, and many of the drawings are attributed to him. Living at the Carlisle Indian School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, from age 17 to 18, Henderson was inspired to record American Indian history and culture in the ledger when he returned to Darlington, Indian Territory, in Oklahoma in 1881.

|

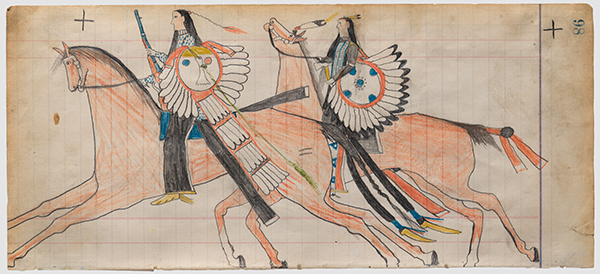

| Attributed to Frank Henderson (1862–1885, Southern Arapaho, Oklahoma), Off to War, from the Henderson Ledger, ca. 1882. Pencil, color pencil, and ink on paper, 5 ⅜" x 11 ⅞" (13.7 x 30.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. (8S-30048) |

Like much ledger art, the Henderson Ledger Artists were concerned with a narrative vision rather than naturalism. The forms of Off to War are flat, defined by contour lines and unmodulated areas of color filling in the forms. In many ways, the flat, pattern-like arrangement of forms is reminiscent of the geometric patterns and linear designs of Arapaho beadwork. Because this work was finished in 1882, well after the Arapaho had moved to Oklahoma, the warrior scene is probably based in the artist's memory.

By the 1840s, when white settlers had penetrated the lands of the Plains Indians, there were still many distinct Plains native groups. From the 1850s to the 1870s, they faced the same problems as other First Nations bands as the U.S. government signed and broke one treaty after another.

There are few First Nations Plains cultures whose art was concerned with narrating historical events or marking time in a linear fashion. There was a narrative tradition in the art of Great Plains cultures such as the Shoshone, Kiowa, Mandan, Cheyenne, and Arapaho. For centuries, most of those visual records consisted of petroglyphs (rock carvings). Eventually the decoration of animal hides became a way to commemorate a coup in battle or historic event. In some societies, visions and dreams were depicted on hides. Women artists painted primarily geometric designs, while men produced records of events.

Even into the Reservation Era (ca. 1870–1890s), when so many cultures had been dispossessed and deported to reservations, many male artists continued to record their accomplishments. This was often in the form of ledger art, so-called because they used what materials they could get their hands on, such as discarded calendars or ledger books. As the Reservation Era progressed, many of these artist-chroniclers harked back to cherished memories of pre-Reservation days. Their painting became more sophisticated as they assimilated Western artistic traditions.

The Arapaho, before white invasion, had territory from northern New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Kansas north into Wyoming and South Dakota. After the treaty of Fort Laramie in 1851, the band separated into northern and southern branches. Treaties in 1867 and 1869 moved the southern Arapaho to west-central Oklahoma, where they are to this day.

More First Nations art in Davis Programs: Explorations in Art 2E Grade 2: 5.7; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 3: 6.7; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 4: Unit 5 intro; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 5: 2.5; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 6: 2.8, 3.8, 4.4, Unit 5 p. 151; A Community Connection 2E: 1.4; A Global Experience 2E: 2.5; Beautiful Stuff from Nature; Section 3 p. 48; Experience Clay 2E: Chapter 2 p. 32, Chapter 5 pp. 147 and 180; Exploring Visual Design 4E: Chapter 11 p. 211

Comments