Indigenous Peoples Heritage Month: Cadzi Cody and Edgar Heap of Birds

My series celebrating National Native American Heritage month concludes today. I have already shown you ancient architecture and ceramics and objects from the 1800s. Now I will show you two artists who span the 20th century.

|

| Charles Washakie (Charlie Katsiecodie,aka Cadzi Cody, 1866–1912, Flathead/Shoshone/Crow), Hunting Buffalo, ca. 1900. Pigments on elk hide, 81" x 78" (205.7 x 198.1 cm). © 2019 Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-4744) |

Cadzi Cody painted scenes of important events in his life before being confined to a reservation. He painted several versions of the Buffalo Hunt, all containing the same important aspects. The Sun Dance, an annual ceremony of fasting and prayer, takes place in the central image of a forked post containing a buffalo head. The Grass Dance, forerunner of the contemporary “pow wow,” flanks that image. As with native beadwork, figures and animals are flat combinations of shapes, represented on a mystical blank background with vertical arrangement meant to indicate depth.

The Shoshone, a branch of the Ute-Aztec people, called themselves Newe, which means “the people.” They inhabited the fringes of the Great Plains until about 1700, when they acquired horses. After which, they roamed vast lands that included present-day Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado. By the 1750s, the area in which the Shoshone roamed was radically diminished to parts of Utah, Wyoming, and Idaho, due partly to the aggression of eastern bands that had acquired guns from the Europeans.

By the 1840s, when white settlers had penetrated their lands, the Shoshone comprised at least seven distinct branches. From the 1850s to the 1870s, they faced the same problems as other First Nations bands, as the US government signed and broke one treaty after another. The Shoshone were eventually settled on reservations in Idaho, Wyoming, Nevada, and Utah.

Great Plains cultures such as the Shoshone, Kiowa, Mandan, Cheyenne, and Arapaho were some of the few First Nations cultures whose art was concerned with chronicling historical events or marking time in a linear fashion. For centuries, those visual records consisted of petroglyphs (rock carvings). Eventually the decoration of animal hides became a way to commemorate a coup in battle or historic event. In some societies, visions and dreams were depicted on hides. Traditionally, women artists painted primarily geometric designs, while men produced records of events.

Cadzi Cody was an Eastern Shoshone living on the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming. Similar to the hide paintings of many of his contemporaries living on reservations, Cody’s work depicts the life he knew before the reservation. This hide depicts the importance of the buffalo hunt to native bands. Hides such as this were worn as a robe representing a visual tally of the individual's hunting prowess. The hides were also used for tepee decoration. Cody is believed to have produced dozens of such painted hides, primarily for trade. Such scenes of First Nations life were popular with whites in the early 1900s, as the traditional way of Indian life went the way of the buffalo.

|

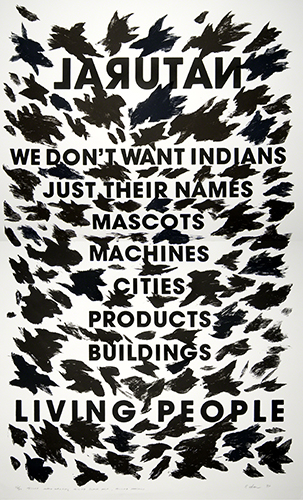

| Edgar Heap of Birds (born Hock E Aye Vi, 1954, Cheyenne/Arapaho, Kansas), Telling Many Magpies, Telling Black Wolf, Telling Hachivi, 1989. Screenprint on paper, 45" x 35" (114.3 x 88.9 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art. © 2019 Edgar Heap of Birds. (PMA-4999) |

Although Edgar Heap of Birds continued to paint after receiving an MFA from the Tyler School of Art and Architecture at Temple University—where he found his voice as an artist—his first public project was a text piece that ran on a digital billboard in Times Square in New York City (1982). It ran alongside the work of Jenny Holzer (born 1950) and Hans Haacke (born 1936), but Heap of Birds’s work was in Cheyenne.

Unlike artists such as Holzer who appropriate sayings, texts, and platitudes from literary sources, Heap of Birds’s works zoom right to the point. They are his open-eyed, critical opinions of the appropriation of native culture, words, symbols, and art by white artists, sports teams, etc. As opposed to Conceptual Art, in which the idea behind the process is considered more important than the finished work, in Heap of Birds’s art the idea and the finished words are the important elements.

The pictorial movement in First Nations art, not an indigenous tradition for most cultures, had its greatest impetus after the establishment of the Santa Fe Indian School in New Mexico in 1932. Established by well-intentioned white teachers, the school encouraged aboriginal students to create depictions of their cultures, albeit in figurative compositions foreign to most native groups.

This Western art-inspired style held dominance until 1958, when Sioux artist Oscar Howe (1915–1983) raised awareness about the neglect of living First Nations artists who incorporated modernism into native subject matter. During the late 1960s, influenced by the Civil Rights, Latino Power, and Feminist Art Movements, First Nations artists began producing social-issue based art in a variety of modernist styles.

Edgar Heap of Birds (born Hock E Aye Vi, “Little Chief”) was born in Wichita, Kansas. He grew up in an urban environment far from the reservation life in Oklahoma where his family originated. An inspiration for Heap of Birds to become an artist was Blackbear Bosin (1912–1980), a Kiowa Comanche artist who was successful in Wichita as an artist, not only on a reservation.

After receiving a BFA at the University of Kansas, Heap of Birds studied at the Royal College of Art in London before attending Tyler. Writing his ideas about native life on his studio walls, the walls became the artwork. Abstraction did not provide the vehicle to express his feelings about historic atrocities against First Nations, nor did narrative painting appeal to him. He began making notes on a myriad of issues concerning First Nations peoples.

Correlations to Davis programs: A Global Pursuit 2E: 2.5; Discovering Art History 4E: 4.10; Discovering Art History Digital: 4.10; The Visual Experience 3E: 14.5

Comments