Kacho-e: Ohara Koson

Today’s post is about my epiphany of the week. In a previous post I introduced you to the early 1900s phenomenon in Japanese woodblock prints called sosaku hanga. That was the continuation of the ukiyo-e style by artists who preferred to draw the subject, cut the woodblock, and print the image themselves. It is the Japanese version of the Arts and Crafts School ideal. On the other hand, the shin hanga artists continued the traditional ukiyo-e method of creating prints: an artist’s sketch going to a woodblock carver then to a printer.

The term shin hanga (new prints) was coined in 1915 by a Japanese publisher who wanted to distinguish contemporary ukiyo-e from that of the past. Influenced by French Impressionism and other Western artistic conventions, the artists of this movement at the beginning of the 1900s produced some of what I absolutely have to drool over. I mean, I tried doing woodblock prints in junior high school…why couldn’t I get registration like these artists???? (sigh)

|

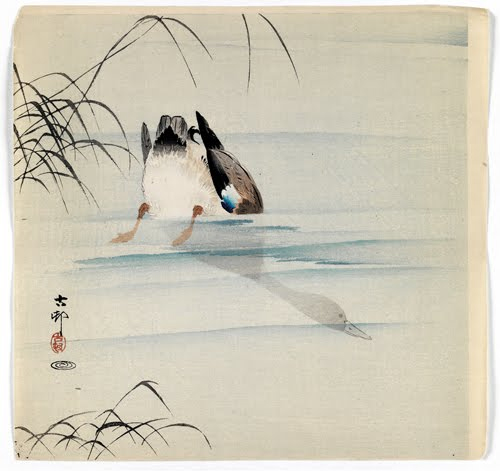

| Ohara Koson (1877–1945, Japan), Diving Mallard, ca. 1910. Color woodblock print, 9 ½" x 9 7/8" (24.1 x 25.1 cm). © Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY. (BMA-2398) |

Kacho-e—birds and flowers (images)—was a traditional subject in Chinese and Japanese art, although ukiyo-e artists, through the woodblock print medium, brought it to its greatest fruition. The artists Hokusai (1760–1849) and Hiroshige (1797–1858) were probably singularly responsible for making the subject so popular in the woodcut medium. But, by the late 1800s in Japan, ukiyo-e prints were becoming eclipsed by Western-introduced lithography as a medium of mass-produced imagery.

However, the genre persevered well into the 1900s because of artists like Ohara Koson. Although these artists preferred the traditional technique of handing over a drawing to a woodblock carver and then a printer, there is a VAST difference in sophistication in the late shin hanga prints. They possess a sensitivity of subject and execution that we see nowhere else, not to mention that the feeling for the subject matter itself that transcends the mere “homage to nature” we see in early ukiyo-e prints.

Koson is considered one of the early 1900s masters of the shin hanga style of kacho-e. Born in Kanazawa as Ohara Matao, Koson’s traditional training included the Japanese custom of a pupil taking a mentor’s name (Susuki Koson/Kason). His main interest was in bird and flower prints, which he had executed in Tokyo by the Kokkeido publishing house, and then later the Daikokuya Company. The majority of Koson’s prints went to the U.S. and Western Europe.

Ironically, later in life, Koson chose to emphasize painting as his primary medium. There was a revival in interest in kacho-e and, in particular, Koson prints after the 1960s. When Japanese scholars wanted to study his prints, most of them had to be imported from the US.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 1: 1.6; Explorations in Art Grade 2; 3.13, 3.14; Explorations in Art Grade 3: 2.8; Explorations in Art Grade 4: 4.20; Explorations in Art Grade 5: 4.21, 4.24, 5.30; A Global Pursuit: 7.3; A Community Connection: 4.3, 8.2; The Visual Experience: 9.4

Comments