Gem of the Month: Kumi Sugaï

Abstraction was not an invention of Western artists in the early 1900s. The following definitions indicate that abstraction has been part of art throughout the world since the cave paintings of pre-history. Abstract art:

- represents an idea or something not of the physical, objective world;

- is a representation of an object in the real world that has been simplified, reduced in detail, or otherwise modified from the real world;

- or conforms visible forms to ideals, rather than represent them as they appear in reality.

My March Gem of the Month artist, Kumi Sugaï, explored the expressive and abstract possibilities of calligraphy characters during several points in his career.

|

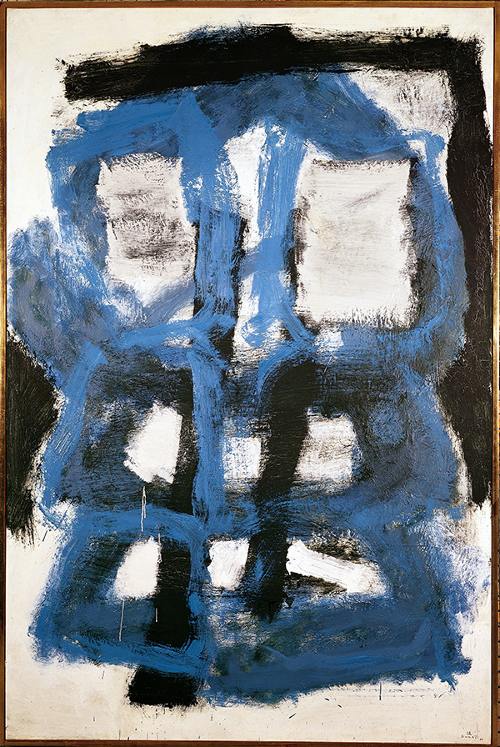

| Kumi Sugaï (1919–1996, Japan), Aooni, 1960. Oil on canvas, 6'6" x 4'4" (195.58 x 129.54 cm). Courtesy of the Buffalo AKG Art Museum, Buffalo, New York. © 2024 Kumi Sugaï / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (AK-1984sgiars) |

Originally from Japan, Sugaï lived in Paris from 1952 until 1969. On arrival in France, Sugaï's style was close in spirit to graffiti, displaying virtually no color. The monochromatic aspect of his art carried over into his works of the mid-1950s. Works such as Aooni reflect his interest in calligraphy and its possibilities as abstract symbols. Despite his affinity for typography, Sugaï's calligraphic-looking forms were painted in a gestural fashion with richly textured surfaces that may reflect the influence of Jackson Pollock’s (1912–1956) action painting. Like the Abstract Expressionists, Sugaï's compositions always respect the boundaries of the canvas, and are typically closed compositions.

Ao oni means "blue demon" in Japanese. It refers to a type of troll in Japanese folklore that is believed to live in the mountains. They are associated with massive strength and power over thunder and lightning. The oni skin is often blue in color. Sugaï alludes to the figures with the energetic, gestural passages of blue in this work.

|

| Kumi Sugaï, Kabuki, 1958. Oil and gild paint on canvas, 4'9" x 3'9” (145.8 x 113.3 cm). Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2024 Kumi Sugaï / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (MOMA-P1970sgiars) |

In his painting Kabuki, Sugaï imitated the movements of Kabuki actors’ arms robed in great kimono sleeves. It is the movement of kimono sleeves and the kimono itself that is of the utmost importance in Kabuki theater dance, rather than the body of the dancer. The simplification of the actor's form to gestural brushstrokes reduces the figure to a form that resembles a calligraphy character.

The forced opening of Japan to Western trade in the 1850s and the collapse of the Tokugawa shogunate (military ruler) in 1868 led to the Meiji “Restoration” (1868–1912). During this time, military leaders attempted to put power back with the emperor. The Meiji leaders wanted to “Westernize" Japan and turn it into an industrialized society like the West so that Japan could become a major power.

After the opening of Japan to the West, the yō-ga (literally “Western style”) school of painting developed in the late 1870s. Not only were Western styles adapted, but also Western media such as oils and watercolors. Almost simultaneously, there arose a group of painters who strove to maintain the traditions of the Kanō school, literati landscape painting, and ukiyo-e. This group was known as the Nihon-ga, or “Japanese style painting” school. Many artists of the period executed works in both styles.

After World War II (1939–1945), a younger generation of artists had lost faith in national traditions about the emperor and traditional Japanese culture. These artists naturally turned to modern Western art with its emphasis on constant change and growth. Some artists embraced abstraction wholeheartedly, while many accommodated Western modernism with some aspects of traditional Japanese art. Part of this artist group sought to reconceptualize calligraphy as a form of contemporary expressionist painting. Calligraphy, an art form in itself, is thousands of years old in China and Japan.

Born in Kobe, Japan, Sugaï was part of the first generation of Japanese artists to learn Western painting techniques. He first experimented with oil colors when he was nine years old. He studied at the Osaka School of Fine Art from 1933 to 1937, when he left to work in commercial advertising during World War II (1939–1945). During the 1940s, Sugaï became familiar with the work of European modernist artists, and later discovered the work of Pollock.

Sugaï's early style in Paris was populated with animals and figures in Surrealist settings. These elements gradually disappeared from Sugaï's work in the mid-1950s. He began to paint large, single calligraphic or geometric shapes, influenced by the free-form abstraction of the French movement Art Informel. During the 1960s, influenced by the automobile, Sugaï's abstractions became hard-edge geometric forms. The hard-edge geometric forms gradually morphed into geometric letters and directional signs. Sugaï reprised large, single-letter works during the 1970s.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art 2E Grade 3: 3.8; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 5: 5.2, 5.3; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 6: 5.5; Experience Art: 6.1; A Personal Journey 2E: 4.2; The Visual Experience 4E: 4.1, p. 98

Comments