Compassion in Art: Honoré Daumier and John Biggers

A couple of mornings ago, a homeless person was in the parking lot of our building yelling his lungs out to get attention at 6:45 am. I feel bad for these folks who have nowhere to land during the day. When one thinks about it, this is an important social issue that has recurred throughout history.

In the ancient world, homeless people would bed down in temple precincts. During the Middle Ages in Europe, churches often housed the homeless. There have been artists throughout history who have taken on the subject as a way of reminding people that these issues persist. Today and tomorrow, I will take a look at this subject in printmaking and photography.

|

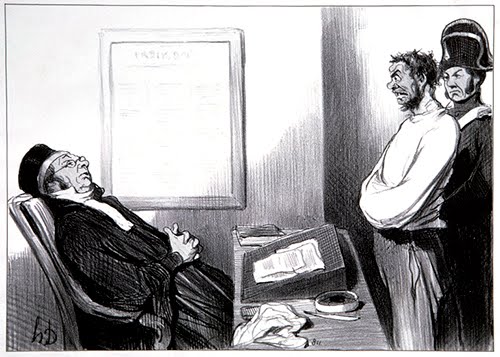

| Honoré Daumier (1808–1879, France), “You were hungry? You were hungry? That’s no excuse! I’m hungry practically every day and I don’t go out and steal bread!,” #15 from the series Men of Justice, published in “Le Charivari” illustrated newspaper, October 20, 1845. Lithograph on paper, 10 7/16" x 13 ¾" (26.5 x 35 cm). Private Collection. © 2018 Davis Art Images (8S-29950) |

Honoré Daumier produced almost 4000 prints in his lifetime. He also supplemented his income with painting. While he did some portraits and genre scenes, many of his paintings concern the same subjects as his prints—the lives of the poor, struggling underclass of the 1800s.

In 1834, a law passed banning outright satire of the government, so Daumier turned his attention to the lower middle class and their struggles. An ardent draughtsman, Daumier elevated the genre of lithography to masterful heights in his exploitation of the possibilities of fine nuances of shading and visual texture. It was during this period that lithography became a serious rival to wood engraving for publications such as newspapers, books, and magazines.

Daumier had a very dim view of judges and lawyers as part of the entrenched government that kept poorer people down. He was also always eager to point out the vast differences between the poor and the rapidly expanding middle class in France. What better way than to show a clueless, fat judge who equivocates the idea of being hungry?

|

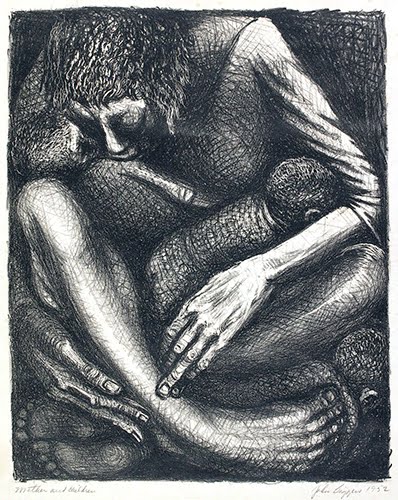

| John Biggers (1924–2001, United States), Mother and Children, 1952. Lithograph on paper, 16 ¾" x 13 3/8" (42.5 x 34 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art. © 2018 John Biggers/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (PMA-4087bivg) |

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s galvanized black artists to push for a revival of exhibitions and the study of African American art. The revival of the black artistic community led to the formation of groups dedicated to integrating common aesthetic problems with a commitment to civil rights. The group Spiral, founded in New York in 1963, elevated awareness of the dual motivations among black artists: art that was relevant—basically narrative—to the black community, and the search for individual modern expression outside of political concerns, which would include abstraction.

The work of John Biggers represents this dichotomy among African American artists. His subject matter addressed concerns of the black community, conveyed in an expressive, abstract visual language. His style is a realism tempered by an abstract simplification seen in African art. He drew his subject matter from his experiences growing up in the South, many of them from the period after his father's death.

The artist produced many versions of Mother and Children. In these personal subjects, Biggers reflected on the larger state of African American communities in America and their experiences. His signature style is a complex network of hatching and cross-hatching to build up form, with an expressive exaggeration. The image of a poor, Southern black woman cradling three hungry children was an image that many African Americans, particularly refugees from tenant farming in the South, could identify with.

Check back tomorrow for part two of my Compassion in Art series, which will take a look at this subject in photographs.

Comments