Compassion in Art: Consuelo Kanaga and Zoe Strauss

My Compassion in Art series continues with a look at the subject in photography.

|

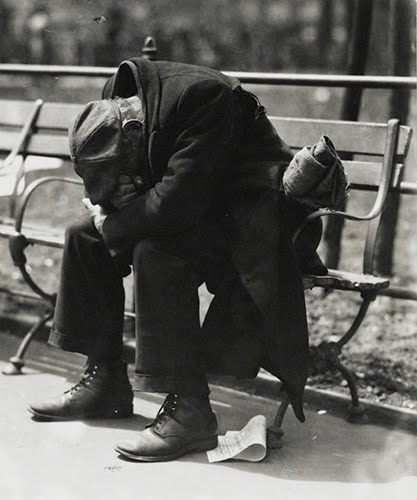

| Consuelo Kanaga (1894–1978, United States), Untitled, 1930s. Gelatin silver print on paper, 4 1/8" x 3 ½" (10.5 x 8.9 cm). Image © 2018 Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY. (BMA-1446) |

Like Dorothea Lange (1895–1965), Berenice Abbott (1898–1991), and Margaret Bourke-White (1904–1971), Consuelo Kanaga was an important documentary photographer in the middle of the 20th century. Unlike her contemporaries, despite a successful career of sixty years, Kanaga received little public acclaim or critical success in her lifetime. Her political and social ideologies guided her art. At a time when most social commentary in photography involved images meant to shock the viewer into action, Kanaga's images seduced the viewer with careful composition, intuitive cropping, and reframing.

Kanaga moved from San Francisco to New York in the 1920s. When first in New York, Kanaga became interested in documenting urban poverty and deprivation. At the same time that she was producing pleasing portraits of middle-class people to support herself, she was also creating sympathetic portraits of the inner-city poor.

The Great Depression (1929–1940) provided Kanaga with ample subject matter in terms of people left with nothing and nowhere to go. Her intent in her documentary photographs was to give the public something to think about to prevent poverty, not to shock or shame them. By choosing a close-up on the man on the bench, her point could hardly be considered subtly accomplished.

|

| Zoe Strauss (born 1970, US), Gunshot in the Leg on Gurney, Philadelphia, 2007/2011. Inkjet print on paper, 12" x 18" (30.5 x 45.9 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art. © 2018 Zoe Strauss. (PMA-7364) |

Zoe Strauss is a native of Philadelphia. Previously known for her public art happenings and installations, Strauss took up photography in 2000, when she embarked on a ten-year project called Under I-95. She went all-in, devoting her life to the project, and came out the other side an elected member of the famed Magnum Photos cooperative.

An epic, open-ended narrative in photographs “about the beauty and struggle of everyday life,” Under I-95 hinged on an annual, one-day exhibition of Strauss’s street photography—in the form of color photocopies priced at five dollars each—on the concrete pillars under an elevated section of Interstate 95 in South Philadelphia. Although she has photographed in other cities and countries, Strauss continues to document the everyday people in neighborhoods of Philadelphia.

Strauss’ work is reflective of the sophisticated evolution of the Snapshot Aesthetic style of photography. The style flowered during the 1960s in the hands of such artists as Diane Arbus (1923–1971) and Garry Winogrand (1928–1984). It mimicked the candid, un-posed, spur-of-the-moment pictures taken by amateurs and middle-class families. Interestingly, between the 1960s and the 2000s, the style has been refined to subtly reveal psychological investigation by the photographer.

What more disturbing element for Strauss to document than the out-of-control gun violence in the US? When you wake up every night at 2 am and hear gun fire in the neighborhood, then that is not a good thing. Unfortunately, as Strauss points out in this photograph, Americans seem to take gun violence casually, even when they are the victim themselves

Read part one, Compassion in Art (Printmaking).

Comments