African American History Month: Theaster Gates and Mickalene Thomas

It is certainly true that, in the 21st century, more African American artists than ever before—in a wider range of expression—are participating in the American “art world.” As African Americans continue to experience injustice in terms of access to education, housing, healthcare, and other basic rights, it is not surprising that Black artists are asking the same questions about the nature of their art as their predecessors in the Harlem Renaissance did.

Although the debate is no longer between “scenes of African and African American life” versus “modernism,” contemporary African American artists realize that they are an important voice in drawing attention to the continued neglect of the African American community. Nowadays, African American artists have added to their narratives issues of women’s rights, queerness, and gender identity.

|

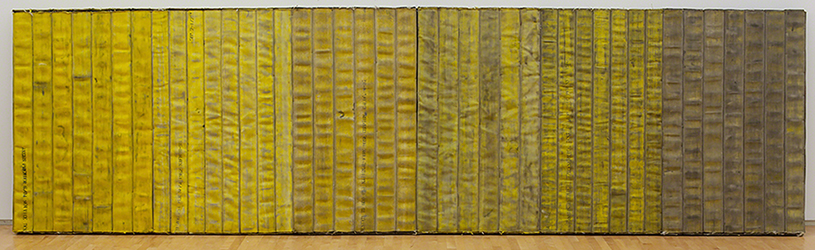

| Theaster Gates (born 1973, US), Civil Tapestry 5, 2012. Decommissioned Chicago Fire Department hoses on oil cloth mounted on wooden panel, 58" x 17'4" x 4" (147.3 x 528.3 x 10.2 cm). Digital image © Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY. Art © 2020 Theaster Gates. (AK-3333) |

Theaster Gates’s series of Civil Tapestry works reference the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s; specifically, the May 1963 peaceful march in Birmingham, Alabama, when African Americans were sprayed with fire hoses to break them up, injuring many. The tactic was used for days afterward. These works also reference the burning of Black churches during the Civil Rights Movement. They are a tribute to African Americans who fought the early struggle for equality and decency.

Civil Tapestry also seems related to the 1968 riots in Chicago after the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., when whole neighborhoods on the South Side of Chicago went up in flames. Gates’s work focuses on neighborhoods and America’s underserved.

Gates began building fire hose murals in 2011. That year, he was named director of the initiative Arts + Public Life (APL) at the University of Chicago. Beginning in 2006, Gates began what would become the Dorchester Projects in the Greater Grand Crossing neighborhood (centered around 7300 South) of Chicago. He bought abandoned structures and, using repurposed materials, turned them into community centers that encourage a cultural revival in the neighborhood. They serve as libraries, a media archive, and a cinema, to name a few.

Gates was born and raised in Chicago, and is currently an artist, educator, social activist, and community rebuilder on the South Side where he grew up. He was raised in East Garfield Park near the DuSable Museum of African American History. As a young man, he was deeply rooted in his church and community, and helped in his father’s roofing business. He received a BS in urban planning from Iowa State University (1996), an MA in fine arts from University of Cape Town (1998), and an MS in urban planning, religious studies, and ceramics from Iowa State University (2006). In 2014, he was appointed a professor in the Visual Arts at the University of Chicago.

|

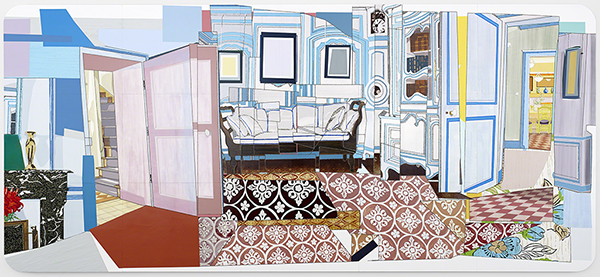

| Mickalene Thomas (born 1971, US), Interior: Monet’s Blue Foyer, 2012. Rhinestone, acrylic, oil, and enamel on canvas mounted on wood panel, 9' x 20' (274.3 x 609.6 cm). Digital image © Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY. Art © 2020 Mickalene Thomas/Artists Rights Society, New York. (AK-3277thoars) |

Mickalene Thomas’s Interior series reflects her ongoing fascination with the aesthetics of the 1970s—during which she grew up—and, more broadly, the inherently white culture espoused by interior designers and advertising in general (unfortunately to the present day). She was inspired to do this series when she came across an edition of the eighteen-volume set of Practical Encyclopedia of Good Decorating and Home Improvement of 1971. The set provided perfect backgrounds for her renowned depictions of Black women in 1970s-inspired interiors, often ornamented with glitter and found two-dimensional materials.

As an extension of her images of African American women of the 1970s, Thomas’s cut and pasted Interior works call into question perceptions of beauty, culture, gender, and “class.” Obviously, the images she adapted from the decorating “encyclopedia” reflected white, Western European-oriented aesthetics. By dissecting and rearranging the styles available in the books, Thomas demonstrates the diversity of cultural influences on American life, whether devoid of African American input or not (usually, in this case, not). Comparing these works to her images of African American women in 1970s settings, there is a stark reminder of the appropriation forced on Black people to “fit in” to American society.

Thomas was born in Camden, NJ, and earned a BFA from Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. She earned an MFA in painting from Yale. Her work is greatly influenced by the collages of Romare Bearden (1911–1988) and by the ironic view of American culture evident in Pop Art. Unlike Pop Art, which catered to the viewing public’s addiction to commercial imagery, Thomas’s work seeks to devalue the influence of common cultural aesthetics foisted on African Americans, particularly by Blaxploitation films of the 1970s that portrayed African Americans as some very unflattering stereotypes.

Comments