Music

An artist picking up his artwork from the latest exhibit in the Davis Art Gallery, In Vision: 2D and 3D Landscape, proposed an idea for an exhibition of art related to jazz music. I’m sure the aesthetic kinship that music has with visual arts has occurred to many of you before, but I never realized it’s expressed in so many different ways!

|

| China, Seated Musician, tomb figurine, ca. 500–550 CE. Earthenware with traces of polychrome, 8 1/4" x 5 1/8" x 4 7/16" (21 x 13 x 11.4 cm). © Albright Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY. (AK-230) |

Wouldn’t it be great to listen to music forever in the afterlife? During the Shang Dynasty (ca. 1523–1027 BCE) aristocratic burials were accompanied by sacrifice of family pets, servants, horses, and guards. From the Zhou Dynasty (1027–256 BCE) through the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE), the human sacrifices were replaced by ceramic figures of familiar human attendants. I’ve always thought this is a nice way to think of the afterlife (not the human sacrifices, obviously).

|

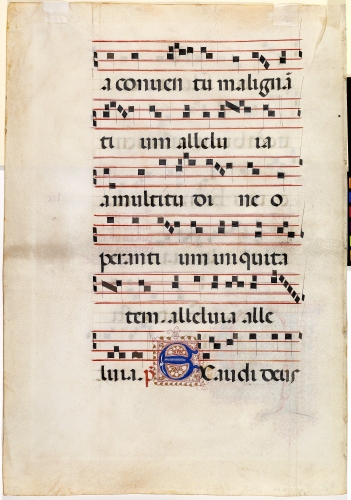

| Italy, Leaf from an antiphonary, 1485. Ink, tempera and gold leaf ln parchment, 17" x 11 3/4" (43.2 x 29.8 cm). © Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY. (AK-1899) |

The visual expression of music can be just as beautiful as the auditory. During the Middle Ages (ca. 500–1400), the major form of painting was manuscript illumination, which continued as an important genre through the Renaissance. Of the many types of books decorated, antiphonaries are among the most striking because of their use during a Christian service. They were extra-large (for manuscripts, that averaged 7 3/4" high), placed on a stand in the choir section of a church, so that monks or nuns could read the music while performing a choral service (they didn’t have printed hymnals).

|

| Attributed to Antoin Sevruguin (1830s–1933, Iranian, born Armenia), Group of Women Musicians, 1890s(?). Silver albumen print on paper, 6 3/16" x 8" (15.7 x 20.5 cm). © Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-2472) |

I’m loving the woman with her eyes closed because the exposure time was probably about 30–60 seconds. What I would love even more is hearing the music they are playing. Sevruguin is an interesting person in the history of photography. A painter by vocation, he gave it up for photography to help support his family. Born of Armenian-Georgian parents in the Russian embassy in Tehran, and he returned to Tehran to set up a photography studio. Although his photographs were meant to appeal to Westerners as “curiosities” about the Middle East, they have provided a valuable document of everyday life in Iran at the time.

|

| Vasily Kandinsky (1866–1944, Russia), Fragment 2 for Composition VII, 1913. Oil on canvas, 34 1/2" x 39 1/4" (87.6 x 99.7 cm). Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY. © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (AK-1812knars) |

Of all the modernist pioneers of the early 1900s, Kandinsky was perhaps the most emphatic in his belief in the connection between music and painting. In his 1912 book On the Spiritual in Art, he proposed that artists should imitate music in their painting in order to achieve an expression that was free from any literary, historical, political, or physical connection. This is probably the reason so many of his paintings are entitled “composition.”

|

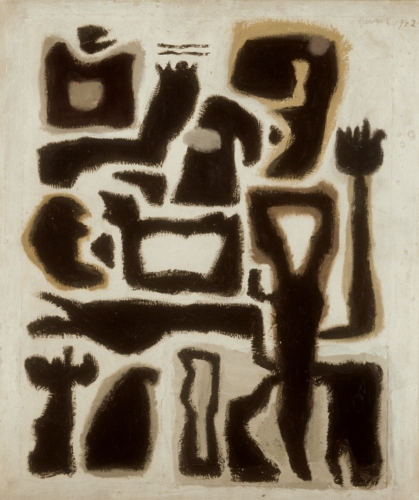

| Willi Baumeister (1889–1955, Germany), Drumbeat, 1942. Oil on cardboard, 20 7/8" x 18 1/8" (53 x 46 cm). Image courtesy of the artist/Davis Art Images. © 2016 Willi Baumeister / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (8S-724bmars) |

Drumbeat is this artist’s visual tribute to the spiritual power of African music, despite the devastation of war. Baumeister was an abstract German artist, in touch with developments in Paris, Munich, and Berlin long before World War II (1939–1945). When his art was branded “degenerate” by the Nazis in 1937, he went underground and kept a low profile during the war. He studied non-Western art, particularly Asian and African, which resulted in a number of series, including his Afrika series of 1942.

|

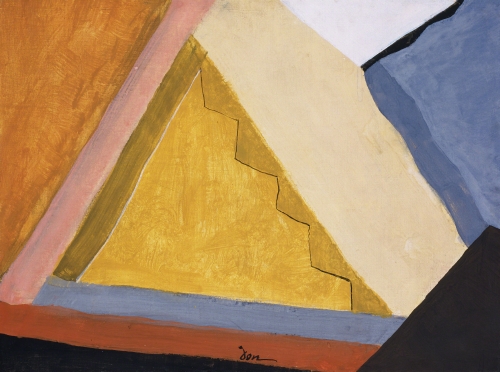

| Arthur Dove (1880–1946, US), Primitive Music, 1944. Gouache on canvas, 18" x 24" (45.7 x 60.9 cm). Image © 2016 The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC. (PC-112) |

Dove may have been referring to the influence of African music in the word “primitive,” because he did a series of paintings based on jazz and swing music in the 1930s and 1940s. He was a pioneer (if not groundbreaking) American modernist, discarding narrative from his paintings as early as 1910, and producing a series of completely non-objective Abstraction works in 1912. He was one of the stalwarts of Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery.

|

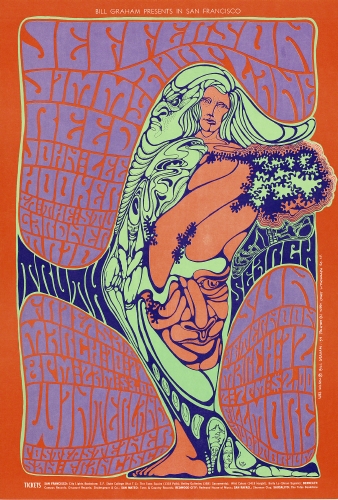

| Robert Wesley Wilson (born 1937, US), Poster for Jefferson Airplane, 1967. Color offset lithograph on paper, 20” x 13 3/4" (50.8 x 34.9 cm). Image © 2016 Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-3968) |

Psychedelic rock music in the 1960s had an amazing effect on Western culture. The psychedelic aesthetic affected fashion, interior design, and, especially, visual arts. Wilson, a native Californian, developed his distinctive graphic style during the seminal counter culture period in San Francisco starting in the mid-1960s. Working in a friend’s printing business, he was free to explore a style influenced by his own political beliefs as well as those of the counter culture around him.

|

| Romare Bearden (1911–1988, US), At Connie’s Inn from the series Of the Blues, 1974. Collage, acrylic and lacquer on Masonite, 50" x 39 3/4" (127 x 101 cm). Brooklyn Museum. © 2016 Romare Bearden Foundation, Licensed by VAGA, New York. (BMA-609bevg) |

Jazz was an important part of Bearden’s life from his childhood, when his father was very involved in the artistic and jazz culture of Harlem in New York. It became an important part of his artistic output. Bearden viewed jazz and blues as a symbol of the energy of humanity, as well as one of the finest achievements pioneered by African Americans. During the 1970s he produced two series of paintings on the subject: Of the Blues and Of Jazz. At Connie’s Inn celebrates one of the famous jazz clubs in Harlem. It is particularly noted for hosting Louis Armstrong (1901–1971), who also happened to be a frequent guest in the Bearden home during his childhood.

|

| Arman (Armand Fernandez, 1928–2005, US, born France), Toccata and Fugue, 1962. Sliced violins mounted on wood, 65" x 52 1/2" x 5 1/4" (165.2 x 133.4 x 13.3 cm). Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY. © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (AK-496amars) |

Wed to an electronic music composer, Arman produced many works that involved musical instruments. He was an important figure in the Neo-Dada aspect of the Pop Art period, producing works that were conglomerations of found objects that he called “accumulations.” His interest in found objects began, like the work of Yves Klein (1928–1962), with impressions made in paint of found, discarded objects—particularly musical instruments—on paper or canvas. These Arman later translated to assemblages of smashed and cut up musical instruments, a comment of the waste of consumer culture.

|

| Mayan People, Guatemala, Marimba Player with Two Quetzal Birds, 1972. Cotton, 24" (height: 61 cm). Private Collection. Image © 2016 Davis Art Images. (8S-21132) |

Textiles have been a major means of artistic expression in Guatemala since the flourishing ancient Mayan cultures of Central America. This tourist weaving depicts a commonly seen street musician playing the marimba. The gourd marimba was an instrument widely used in West Africa, and evolved in Central America during the 1400s and 1500s. The first historically documented Mayan gourd marimba in Central America was in Guatemala in 1680. Accompanying the marimba player are two quetzal birds, the national symbol of Guatemala, and an important iconography in ancient Mayan art.

|

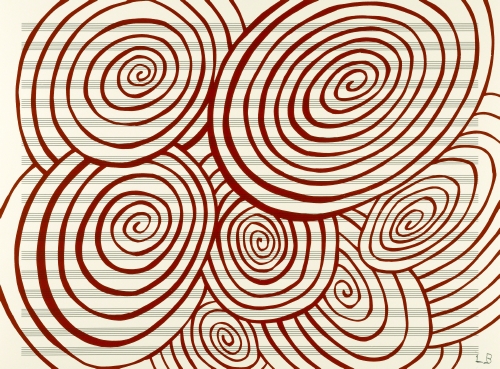

| Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010, US, born France), Untitled, from the portfolio Fugue, 2003/2005. Screenprint on lithographed music sheet, 11 13/16" x 15 15/16" (30 x 40.6 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2016 Louise Bourgeois/The Easton Foundation, Licensed by VAGA, New York. (MOMA-P3803brvg) |

Bourgeois is renowned as a pioneer abstract sculptor, but later in her career explored printmaking extensively. “Fugue” is a musical term. It describes a contrapuntal or polyphonic composition, but can also refer to the appearance of an idea and its reappearance in an alternate form. In a fugue, a main theme is introduced followed by variations in several voices, or parts. After that the principal idea is reintroduced. In Bourgeois’ Fugue certain aspects create compositional contrasts, such as the regularity of the spirals on one sheet and squares with rectangles on another.

Comments