African American History Month 2018 II

Let us not forget that African American artists have existed since the founding of America. Unfortunately, they were not colonists, but forced here as slaves on Dutch, Portuguese, French, Spanish, and British ships. Many of those artists represent aspects of American art history that get very little reportage (classy, huh?). Yet, they are fascinating pieces to the puzzle that constitutes American art history.

Some of these artists are only known by their advertisements in papers or by the customers for whom they did work. When one digs deeply into the history of African Americans in the American colonies, it’s an eye opener.

|

| Thomas Gross, Jr. (1775–1839, US), Chest-on-Chest, 1805–1810. Mahogany, yellow poplar, pine, and brass fittings, 82 ¾" x 43 ¼" x 22 ½" (210.2 x 109.9 x 57.2 cm). © 2018 Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-1927) |

Very little is known about Thomas Gross, Jr. (1775–1839), a cabinetmaker in the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia. He is thought to have been a former slave who specialized in large chest-on-chest pieces of furniture. He also operated as an undertaker, as did many cabinetmakers in the early United States. Like many freedmen, he most likely learned cabinetmaking while a slave, and learned all of the most fashionable styles of furniture at the time, which were based on pattern books that came from Britain.

This cabinet does not really reflect any of the contemporary British styles such as Chippendale, Sheraton, or Hepplewhite. These British styles usually had bombé (curving) fronts. This reflects more the contemporary simple, utilitarian style of Pennsylvania German or Amish chest-on-chests, as well as the geometric simplicity of Neoclassicism.

Germantown, a settlement of German immigrants in 1683, was the first town in America to issue a protest against slavery in 1688. Slavery was not banned in the colony until 1780, but Germantown became host to a large community of freed African Americans. Ironically, it was also the home to one of the largest and last of the major slave-holding plantations in Philadelphia, the Chew family of the Clivedenestate. Despite outlawing of slavery in 1780, the state of Philadelphia’s manumission (freedman) law allowed slave holding until 1840.

|

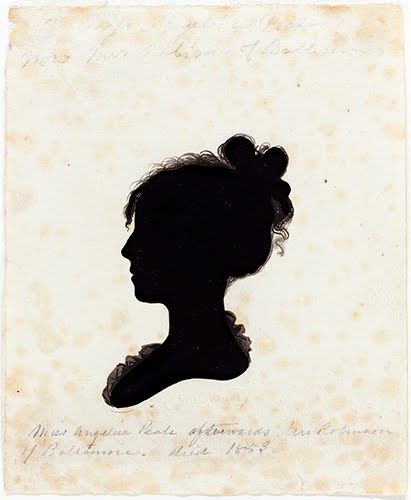

| Moses Williams (1777–ca. 1825, US), Silhouette of Angelica Peale, later Mrs. Robinson (died 1853). Hollow-cut silhouette with black ink on paper, sheet: 4 7/8" x 4" (12.4 x 10.3 cm). © 2018 Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-5241) |

Speaking of freedmen, Moses Williams (1777–ca. 1825) typifies the situation of the children of emancipated enslaved people, who were required to remain in the slave owner’s household until the age of twenty-seven, according to manumission laws. Williams's owner was Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827), the patriarch of the first American dynasty of painters. Williams was the son of Scarborough and Lucy Peale. Slaves often took their owner’s last name. Peale freed Scarborough and Lucy in 1786, and Scarborough subsequently took the name of John Williams. Moses, however, stayed behind in the Peale household, raised with the Peale children and trained as an artist.

At an early age, Moses developed his talent creating silhouette portraits, at the time called “shadow portraits,” “profile portraits,” or “shade portraits.” He learned to use the newly invented “physiognotrace” (face-tracing) machine. This device (originally called physionotrace)—invented by Gilles-Louis Chrétien (1754–1811)—used a lens to transmit the sitter’s likeness to an etching needle. The machine was upgraded in America by John Isaac Hawkins (1772–1855) to traced around the subjects face with an actual bar connected to a pantograph (a system to copy drawings in different sizes via a series of connected rods), which reduced the silhouette to less than two inches (5.1 cm).

Silhouettes were popular until the 1840s when Daguerreotype and calotype photographs became easier and cheaper methods of portraiture. The genre continued through the late 1800s, although it was no longer fashionable. Moses created silhouettes in a combination of cut out paper that was adhered to white paper. He then augmented it with small details in black ink or gouache. He did silhouettes of all of the Peale family, and some 800 beyond that. Like all of the other Peale children, Angelica, portrayed in this silhouette, was a gifted painter of still life.

View all of the posts in my African American [Art] History Month 2018 series.

Comments