|

|

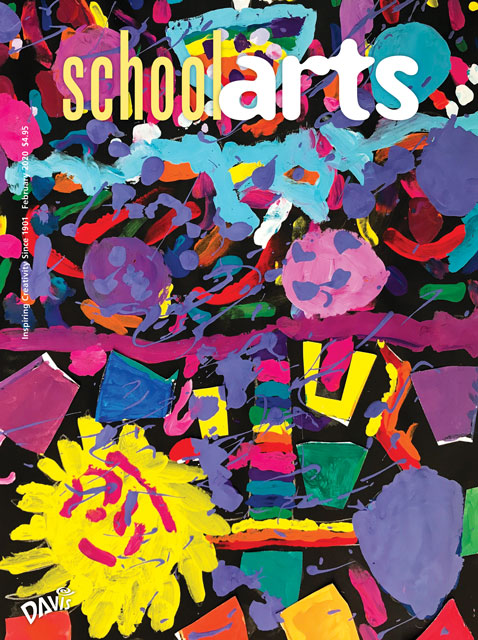

| Top to bottom: Mimi T., gender identity. Lynn P., climate change. |

As a district, our curriculum focuses on Big Ideas, or what I like to call “human issues,” to include contemporary issues for level two high-school art students. The Big Idea is meant to inspire students to create an individualized response to a visual problem that they feel strongly about.

Discussing Protest Posters

We began by looking at and discussing historical and contemporary protest posters via a slideshow presentation. We focused on how protest posters are used to change the way others perceive or think about an issue. Our starting point was the depiction of contemporary issues over the past year on Time magazine covers. We also discussed posters by contemporary artists that were recently featured in the Washington Post, such as Carson Ellis (Killed by the Police), Peter O. Zierlein (And Nevertheless She Persisted), and Rajiv Fernandez (Immigrant Lady Liberty).

Exploring Historical Posters

We explored historical poster artists Tomi Ungerer (Vietnam War Protest), AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power or ACT UP (AIDS Crisis), Black Panther Party, students at the École des Beaux Arts (French Protest), students gathered at the Rhode Island School of Design (Vietnam War Protest), Japanese artist Masuteru Aoba (Non- Violence and Environmentalism), Seymour Chwast (Vietnam War Protest), David Weidman (Watts Riots), Shigeo Fukuda (Warsaw War), Ben Shahn (Nazi Brutality), Copper Greene (Iraq Prisoner Abuse), and Glenn Ligon (Sanitation Worker Protest).

We also discussed historical artwork depicting contemporary issues of the day, such as Hannah Höch’s Untitled (Large Hand Over Woman’s Head), 1930; Diego Rivera’s The Uprising 1931; Jacob Lawrence’s One of the largest race riots occurred in East St. Louis; Gordon Parks’s American Gothic, Washington, DC., 1942; William Kentridge’s still from Felix in Exile, 1994; and Nancy Spero’s Search and Destroy, 1967.

Generating Ideas

Following research, we brainstormed collaboratively to generate and share multiple ideas of contemporary issues that students are passionate about and how they might like to change the way others think about those issues. Ideas that emerged included: school shootings, suicide, hunting, mental illness, homelessness, drug abuse, tobacco abuse, transgender equality, climate change, and animal abuse.

Using ideas generated, students planned three potential thumbnail sketches for their posters, illustrating what elements would be included in the poster and how they would be arranged. After sharing and discussing their ideas as a class, we reviewed our rubric outlining the final dimensions, process steps, and the software and tools that would be used to create the project.

|

|

| Top to bottom: Amaria W., racism. Jennifer V., LGBTQ+ equality. |

Going Digital

Students further developed digital drawing skills using a vector graphics editor and/or photographic composite skills using Photoshop. Students could use either original or public domain photography. Final artwork could also include text to enhance their message. Students would address the use of color, scale, hierarchy, focal point, visual interest of overall composition, and whether or not they successfully communicated their message.

Class Critiques

At the midpoint in production, we conducted a class critique to evaluate and communicate how student ideas were coming together visually, and to allow for sharing of ideas aboutproduction methods and conceptual strength.

After printing and mounting the finished posters, a final class critique was conducted to share insight about the strength of the overall protest message and how it was accomplished on a technical level using the digital software and equipment.

Making a Statement

Because of the controversial aspect of many of the protest topics, such as school shootings, students were asked to write a brief artist statement to explain why they chose their topic and how they hoped they could change the way the viewer perceives or responds to it without feeling threatened. These students learned about form, theme, and context through the visualization and production of this assignment, and benefited by being able to express an idea or opinion about an issue of importance to them personally.

Leslie O’Shaughnessy is an art teacher at Lee High School in Springfield, Virginia. lboshaughnes@fcps.edu

NATIONAL STANDARD

Connecting: Relating artistic ideas and work with personal meaning and external context.

View this article in the digital edition.