|

|

|

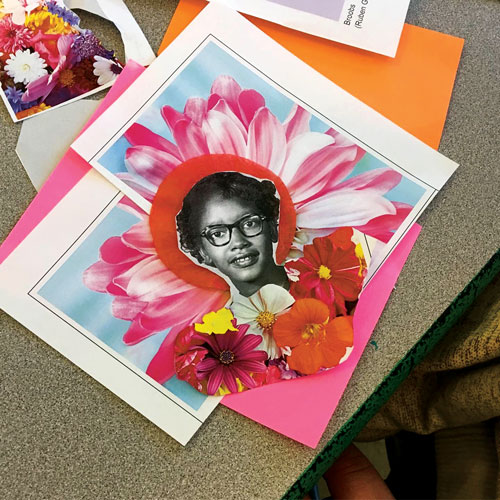

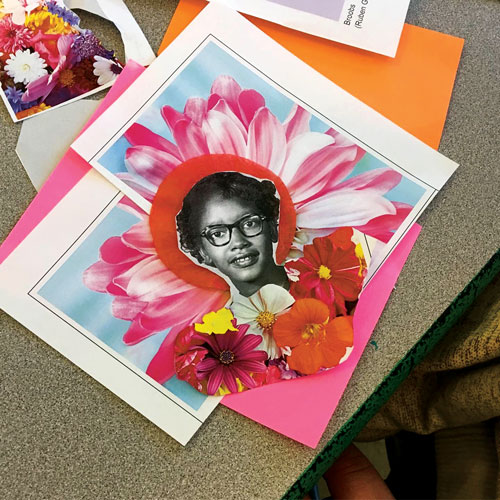

| Top: Makayla Guerrero, Katherine Johnson, grade five. Middle: Maya Agyemang-Prempeh, Kwame Ture (Stokely Carmichael), grade five. Bottom: Students created buttons with each collage tribute for visitors to the civil rights share. |

Investigating Iconography

Students described the images and considered questions about the format and content as well as abstract wonderings about meaning and intention. Some recognized iconographic motifs from their own experiences with religion. Everyone agreed that motifs such as frames, specific poses, and halos drew attention to particular figures and denoted importance or holiness. Students began to create working definitions for iconography that included “a sign that tells you someone is important” and “an image that gets used over and over to mean something.”

Next, we looked at the artwork of Kehinde Wiley and Rodriguez Calero, contemporary artists who draw from and manipulate religious iconography in portraits of ordinary people. Students immediately recognized halos, poses, patterns, and colors that referenced the historic images they studied the day before.

I then asked students to discuss with a partner why they thought these artists used these motifs to create portraits. Students used specific examples from the images as evidence for their ideas: “Just in life these people don’t seem special. But I think the artist wants them to be.” “He takes someone ordinary and makes them seem like a saint—like you should know them.”

Students pointed out halos, deep rich colors, gold, and brocade patterns to show that the artists were trying to make us see ordinary people as icons, people to be honored as holy.

A Focus on Ruben Guadalupe Marquez

The next day, I introduced the work of Ruben Guadalupe Marquez and we began to connect our iconography study to students’ civil rights movement work. Marquez’s collage tributes include many elements of devotional art, and after years of collage work in the art room, I knew students would find the work accessible and appealing.

At our school, we work to examine information through a social justice lens. I include race, origin, gender, sexuality, and other points of identity when introducing artists to students— to name, celebrate, and also normalize all aspects of personal identity. I introduced Marquez as a Latinx, queer artist who began creating devotional artwork specifically to raise up and celebrate transgender people of color.

We looked at a collection of Marquez’s work and identified the people in each image, talking briefly about who they were. Students were struck with the way applying iconographic references elevated the subject and communicated the intention to honor the person. One student said, “Gay isn’t allowed in church. Maybe that’s why they get a halo and he makes them important.” Other students explained that, “it mattered to the artist that they appeared holy” and, “maybe it was a protest.”

Analyzing Style

Before creating collages in Marquez’s style to honor a person from their civil rights study, students came up with this list that they felt generalized his style:

- His collages have a symmetrical frame created with flowers. (One student noticed that the frame resembles the teardrop shape of a flame nimbus in Indian Buddhist artworks.)

- Colors are vibrant and figures have solid-colored or patterned halos.

- The collages have a solid color background.

|

|

| Top: Surya Padippurikkal, Rosa Parks, grade five. Bottom: Student Michael Cruz Grullon plans his collage composition for Audrey Faye Hendricks. |

Art-making Process

Students selected a civil rights activist from their research in class, found an open source photo, and played with composition using flower images that I printed and photocopied, along with cut-out flowers and greenery from magazines. Each student decided on a final composition, consistent with Marquez’s style, then carefully trimmed each collage element with scissors and used all-purpose stick flat paste to glue their collage together.

The final images include references to iconography and to Marquez’s unique style. Several students also added a new iconic motif: flower petals arranged as angel wings, a devotional art reference that they felt elevated their subject. Students used their prior research to write short biographical captions for their subjects.

Students’ artwork and captions were shared with families, other students, and staff as part of the culmination of the fifth-grade civil rights movement work. We also took pictures of their images and reduced them down, and then students devoted an entire afternoon creating buttons for visitors to the civil rights share to keep.

As a final reflection, students selected one contemporary art image to lay alongside their own work and then labeled and annotated both images, identifying iconographic motifs and making comparisons between the two artworks.

Kendra Sibley is a K–8 art teacher at Bronx Community Charter School in New York. kendra@bronxcommunity.org Instagram: @bxcart

View this article in the digital edition.