Recognizing Pride Month: Mary Ann Willson

In recognition of Pride Month, I am presenting two gay artists, both of whom you’ve seen before on this blog: Mary Ann Willson and Glenn Ligon. I chose these two artists because their stories are affecting, although they are separated by more than a century and a half of US history. It’s amazing how much…and how little has changed in that span of time for the LGBTQ+ community.

|

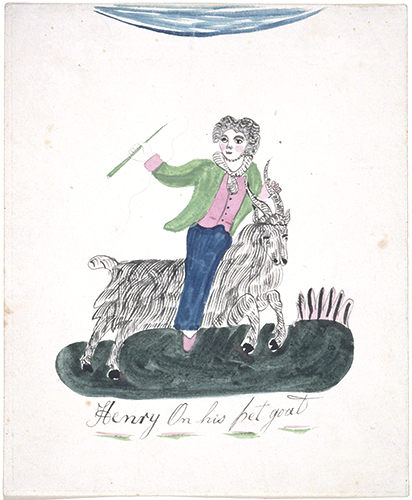

| Mary Ann Willson (active ca. 1800–1825, US), Henry on His Pet Goat. Graphite, watercolor and black ink on paper, 7 7/8" x 6 ½" (20 x 16.5 cm). © 2019 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (MFAB-170) |

This week I will focus on Mary Ann Willson:

Next to nothing is known about Mary Ann Willson except what comes from two anonymous letters. One came with a portfolio bought by the Harry Stone Gallery in New York. A biography of the artist was published in 1894 in Richard Lionel De Lisser's Picturesque Catskills, Greene County. Both letters mention Thomas Cole (1801–1848), Asher B. Durand (1796–1886), and Daniel Huntington (1816–1906) as "modern" artists. This may date the letters to the mid-1800s. Theodore Cole, son of Thomas Cole, apparently owned two of Willson’s prints, and some art historians postulate that he may have written the letters.

According to the letters, Willson and her wife (referred to as “friend”), “Miss Brundage,” moved from Connecticut to Greenville, New York around 1810. They bought a farm together, and while Miss Brundage worked the farm, Willson produced watercolors that, according to the letter-writer, were sold from Canada down to Alabama.

Willson’s work is an example of a self-taught Visionary Art with an emphasis on subject matter and extreme details in costume and jewelry. She used berry juice, brick dust, and charcoal to color her works. Her paintings have a naïve perception of the human form, space, and composition. She seems to have acquired her subject matter from popular prints of the day, particularly fashion illustrations, even when they were ostensibly portraits, such as in Henry on His Pet Goat.

That being said, this work obviously made it as far as Pennsylvania, where it was copied by a German immigrant artist in 1832 in bright, warm colors. The naive sophistication of this work, along with the contrasting areas of energetic contour lines and flat color gives Willson's work a strong early American charm.

Willson was reported to have been devastated after the death of her wife in 1825. No further watercolors were produced after that date, and Mary Ann Willson disappeared from the art world. What she left behind was a wonderful body of work that gives insights to rural American frontier in the early days of the country, produced by a self-taught artist. Willson's story inspired Isabel Miller's 1972 novel Patience and Sarah.

Stay tuned for next week’s post about Glenn Ligon.

Comments