Workus Interruptus (Vacation): Art from Switzerland

Even though I’m half Swiss, I’m not really a Swissaholic. I just happen to see a lot of art that happens to be from Switzerland that also happens to be worth sharing. I’m going on vacay and thought I’d leave you with a Swiss kiss of art.

|

| Switzerland, Wardrobe, from Toggenburg, Sankt Gallen, 1827. Painted wood, 69 3/4" x 56 ½" x 26 ½" (177.2 x 143.5 x 67.3). © 2017 Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-6672) |

When I was little my mother dragged me and my brother to lots of castles. Some of the ones in larger cities would inevitably have at least one room that was furnished in the Rococo style, which was the favored style by the fyni Lüt. This is what my grandmother called the landed gentry, who were governors of areas of cantons, basically a landed upper class. Since Switzerland had no royal court or princely courts or dukedoms, the upper classes in many parts of Switzerland aped French fashions. That lasted until the first Napoleon forced thousands of Swiss men in on his dumb Grand Armée campaign to invade Russia.

That was in central and western Switzerland. In the far eastern part of Switzerland—Ostschwyz, as we say—there may have been French tastes among the elite, but they were executed in the form of painted furniture, rather than finely carved and gilt furniture like French Rococo. The designer of this armoire was definitely into the Rococo arabesques (rocaille), but the little landscape scenes painted in the roundels are straight out of the Danube painting school going back to the 1500s. The roundels may be attempts at Chinoiserie

Toggenburg, now part of the canton of Sankt Gallen, was part of the Protestant-Catholic strife in the early 1700s. It was finally united with Sankt Gallen in 1803 when the Federal Republic was established.

|

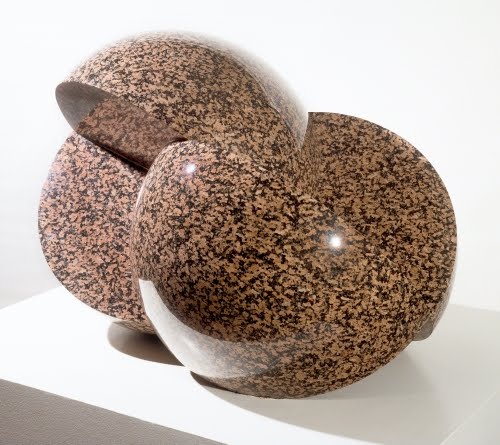

| Max Bill (1908–1994 Switzerland), Striving Forces of a Sphere, 1966–1967. Granite, 23 ½" x 35 ½" x 23 ½" (59.7 x 90.2 x 59.7 cm). Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY. © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (AK-1007bfars) |

Like many other Swiss artists in the first half of the 1900s, Max Bill, born in Winterthur, studied at the Bauhaus in Dessau under Josef Albers (1888–1976) from 1927 to 1929. He is probably one of the most ardent theorists of the Concrete Art aesthetic. The term “concrete” art was coined in 1930 by de Stijl artist Theo van Doesburg (1883–1931) to reference pure abstraction. De Stijl artists reduced art to simple geometric shapes. They felt that the term abstraction implied reduction from a natural form instead of fundamental forms divorced from all reference to the natural world.

Bill initially exhibited with the French abstraction group Abstraction-Création, and organized Concrete Art exhibits in the 1930s. He revived the importance of the aesthetic after World War II (1939–1945). Bill firmly believed that art always had had a mathematical origin, whether conscious or unconscious on the artist’s part. In sculpture, the forms that intrigued Bill the most were the spiral and the sphere. Works such as Striving Forces of a Sphere are Bill’s idea of an endlessly transforming shape that exudes the qualities of rationalism, clarity, and harmony. Although he is renowned as a graphic designer, I really like Bill’s sculptures the best.

|

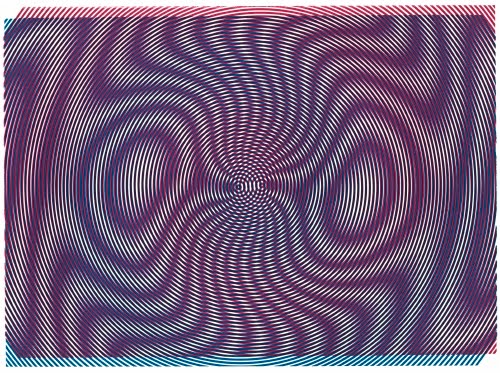

| John Armleder (born 1948, Switzerland), Untitled from the Supernova portfolio, 2003. Lithograph on paper, 22" x 30" (55.9 x 76.2 cm). Photo © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Art © 2017 John Armleder. (MOMA-P3624) |

The question with contemporary artists is no longer “What is Art?” as it was in the early 1900s with Dada and Surrealist artists. Now it is the concern with how an artist’s ideas are reflected in the creative process. Which is more important, the idea or the result of the idea? The Conceptual Art movement that began in the 1960s immersed itself with that question, as did the loose international group of performance and visual artists called Fluxus. They called for the overturning of traditional perceptions of physical art in favor of both mental and visual perceptions.

John Armleder was at one time associated with Fluxus. Born in Geneva, where he studied art at the School of Fine Arts, Armleder is a painter, sculptor, performance artist, and installation artist. The Fluxus movement rejected the idea of “star artists” after the sensation caused by Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art. That sentiment was revived during the greed-fueled, entrepreneurial art scene of the 1980s. Armleder’s body of work is concerned with anti-establishment and anti-commercialist works. In 1969, with other Geneva artists, Armleder co-founded Groupe Ecart, a performance and installation vehicle that was concerned with abandoning traditional hierarchies of art media.

The group of prints in Armleder’s Supernova portfolio embraces the idea of anti-star power by mimicking a variety of divergent styles from Abstract Expressionism to Op Art in only a vague nod to the strict canons of those movements. Armleder invites the exhibiting space to hang these 20 prints in any combination or alone, vertically, horizontally or diagonally. This underscores Armleder’s belief that the art has a life of its own, independent of the artist and certainly independent of commission-hungry sales galleries.

Comments