Women's History Month: Lucretia Mott

The beginnings of the women’s rights movement in the United States occurred at the same time as early developments in photography in this country. To celebrate Women’s History Month, I present a photographic portrait of an important women’s rights advocate: Lucretia Coffin Mott (1793–1880).

|

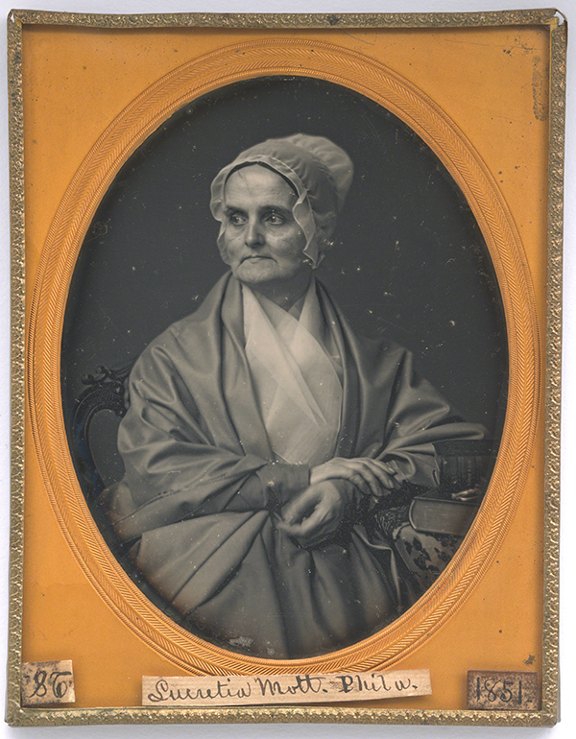

| Marcus Aurelius Root (1808–1888, U.S.), Lucretia Coffin Mott, 1851. Half-plate daguerreotype, image: 4 9/16" x 3 ½" (11.6 x 8.9 cm). © 2024 National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, gift of Irwin Reichstein. (SI-25) |

Born on Nantucket in Massachusetts, Mott moved to Boston with her family when she was 10. Raised a Quaker, Mott was taught to value equality for all. After moving to Philadelphia with her family, she married James Mott (1788–1868) in 1811. In the 1830s, Mott and her husband became involved in the abolitionist movement. In 1833, she was a founding member of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society.

Mott was rejected from the 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention in London because she was a woman. This compelled her to expand her activities to championing the cause of women’s rights. In 1848, Mott was one of the organizers of the famous Seneca Falls Convention, which demanded rights for women and the right to vote. Her 1849 speech, “Discourse on Women,” was an account of the history of women's repression. She became the first president of the American Equal Rights Association in 1866. Mott was also active in the establishment of Swarthmore College, ensuring that it was coeducational.

Photography was recognized as an ideal medium for portraits from its inception. Indeed, in the first three decades after it was invented in the 1820s, most photography was of portraits. By the mid-1800s, miniatures, silhouettes, camera lucida drawings, and photographs were available to serve the demand for portraits among the rising middle class. Studios devoted strictly to portraits opened in all of the major cities of Europe, as well as New York, Boston, and Washington, DC. One of the earliest types of portraiture was straight portraiture, a straightforward record of the sitter.

The Daguerreotype was a popular photographic medium in the early days of portraiture. This French photography process was introduced to the United States in 1839. Within three years, it was wildly popular in the United States. The Daguerreotype produced a one-of-a-kind image that developed on a highly polished silver-coated copper plate. The image produced was a positive. Because the metal plate was delicate—damaged from fingerprints or moisture—it was usually mounted in a case, under glass in a leather- or velvet-bound cover. Mounting a portrait likeness in a special case to protect it harkens back to the miniature or silhouette, which were treated in a similar fashion.

By the late 1840s, American photographers were using smaller plates that cut the exposure time from ten or twenty minutes down to 65 seconds. The main drawback to the Daguerreotype process is that it did not produce a negative from which a large number of prints could be made. If a customer desired multiple images, the photographer had to take several shots.

Photographer Marcus Aurelius Root was born in Granville, Ohio. He initially studied painting and taught penmanship and drawing. Around 1843, Root learned the Daguerreotype process in Philadelphia. The next year, he became a partner in Daguerreotype studios in Mobile, Alabama, and New Orleans, Louisiana. Later, he became partner in a Saint Louis studio, and ultimately one in Philadelphia. He also established a studio in New York that lasted until 1857. Root exhibited his Daguerreotypes widely, including in Europe.

After a railroad accident, he turned to writing extensively about photography history and aesthetics. Root strove to raise the quality of Daguerreotype portraits and the public's appreciation of photography as fine art. He wrote about the need to create a comfortable environment for sitters, recommending that Daguerreotype photographers fill their studios with paintings and books that would elevate the sitters' thoughts.

Correlations to Davis Programs: Focus on Photography 2E: pp. 6–7, 32–33, 134–135

Comments