What's in a Number? Ancient Persia, Anna Claypoole Peale, McKim Mead and White

It’s 2018 now. Does the number eighteen conjure up anything for you? A lot of people make a big deal about turning age eighteen, but for me that just conjures up nightmares of bullying, a face blooming with pimples, and being 6'2" and 104 lbs. I was, however, at eighteen, a budding art historian (go figure). I propose that we look at a variety of great art that has the number eighteen in its dating (or presumed dating).

|

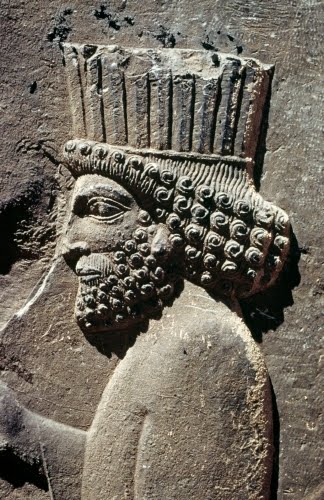

| Ancient Persia, Persian Guard, relief from the Hall of 100 Columns, Palace of Darius I, Persepolis, Iran, 518–ca. 460 BCE. Image © 2018 Davis Art Images. (8S-10204) |

I think the reliefs on the walls of the buildings at Persepolis are among the most beautiful of ancient sculpture. They combine aspects of both Near Eastern and Greek art. I’m always especially fascinated by the way hair and beards are meticulously delineated.

Although these reliefs may have been inspired by those decorating Assyrian (1365–609 BCE) palaces, Persian sculpture is more refined. The figures project more from the surface than Assyrian reliefs, and the forms are more rounded. The treatment of the clothing is reminiscent of archaic Greek (776–480 BCE) sculpture, which seems to have been an influence on art of the Achaemenid Persian empire (550–330 BCE).

Around 550 BCE, the Persians—a formerly nomadic, Indo-European speaking culture from Iran—began seizing power from the region of Persis in southwest Iran, present-day Fars. They were the descendants of Achaemenes, a 600s BCE Iranian ruler in southwest Iran under Assyrian domination. By 539 BCE, the Persians—under Cyrus the Great Achaemenes (ca.600/576–530 BCE)—controlled Babylonia and Media, which covered northern Anatolia and some of the Aegean islands to the west. Under the rule of the king Darius (born 550 BCE, ruled ca. 521–486 BCE), the Persian empire was at its greatest extent, and Darius built a new capital at Parsa (the Greek “Persepolis”). An inscription on the south terrace indicates that Darius built the city as his capital.

|

| Anna Claypoole Peale (1791–1878 US), Portrait Miniature of an Unknown Woman, 1818. Watercolor on ivory, 2 7/8" x 2 ¼" (7.3 x 5.7 cm). © 2018 Art Institute of Chicago. (AIC-337) |

I’m fascinated with American portrait miniatures, if not for the historical nature of the genre before photography, then for the technique of watercolor on ivory. I’ve convinced myself that the ivory must have been scored and gessoed to retain watercolor. I know a woman who does miniatures now and she never could explain to me how watercolor stays on ivory. Nonetheless, such delicate portraits like this are a tribute to patience, if nothing else.

Although not as well known as her younger sister Sarah Miriam Peale (1800–1889), Anna Claypoole Peale was a member of the first American artistic dynasty. She was the niece of Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827), the “founder” of the dynasty. Trained by her father, James Peale (1749–1831), Anna sold her first two paintings—copies of French landscapes—at the age of 14. She played an important role in the cultural development of Philadelphia in the early 1800s.

Peale was born and spent most of her life in Philadelphia, although she also made trips to Washington, DC; Boston; Baltimore; and New York to fulfill portrait commissions. Although she relied primarily portrait miniature commissions for income after 1823, she also continued to paint full-scale portraits, landscapes, and still life.

In 1824, Peale and Sarah Miriam were the first two women to be elected members of the prestigious Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Between 1824 and 1842, Anna’s reputation was such that she had more commissions than she could comfortably handle. She retired from painting in 1841 after her second marriage.

|

| McKim, Mead, and White (firm operated 1880–1961, New York), Honore Family Tomb, Graceland Cemetery, Chicago, probably 1918. Image © 2018 Davis Art Images. (8S-13596) |

This is one of the more “modest” mausoleums at Graceland Cemetery in Chicago. It is the residing place of the Honore family, natives of Kentucky who moved to Chicago in 1855 and became millionaires in real estate speculation. This tomb is across “the street” from the Palmer tomb, a family one of the Honore daughters married into. The Palmers were key in establishing the Art Institute of Chicago, and were also big real estate moguls (see the Palmer House Hilton and Towers between State and Wabash).

If you ever spend any time at all in Chicago, Graceland Cemetery is a must-see destination. It is like a history book of Chicago elite of the 1800s and early 1900s. The cemetery was relocated from Lincoln Park in 1860 when malaria and cholera were threatened because of the Lake Michigan water seeping into tombs (yuck). It soon became surrounded as the city grew, and boasts graves of such famous people as Louis Sullivan, Mies van der Rohe, Cyrus McCormick, Marshall Field, and even a Titanic fatality, Arthur Ryerson.

The architecture firm of McKim, Mead, and White made it big in the late 1800s mania for revival style architecture, particularly Beaux-Arts Classicism, which was another vein of Baroque Revival. The founding partners were Charles F. McKim (1847–1909) and William R. Mead (1846–1928). They were joined in 1879 by Stanford White (1853–1906). White, like McKim, had worked for Henry Hobson Richardson, the great architecture god of Romanesque Revival. While specializing in Beaux-Arts Classicism (good for bank façades), they hired scads of other architects for their numerous commissions, many in the also trendy Gothic Revival, like the Honore Tomb.

Comments