Universal Human Rights Month: Conrad Botes

Artist Conrad Botes began his satirical work in the form of bitingly sarcastic, often abrasive comics from a studio he co-founded called Bitterkomix. He publishes comics to this day, alongside creating paintings and prints. Botes homes in on post-Apartheid failures in justice and government, as well as the still-present social hierarchies that poisoned the culture in the past. He mocks conventional perceptions of individualism, humanism, and conceit that mask the ever-present racial and social dissimilarities in South Africa.

|

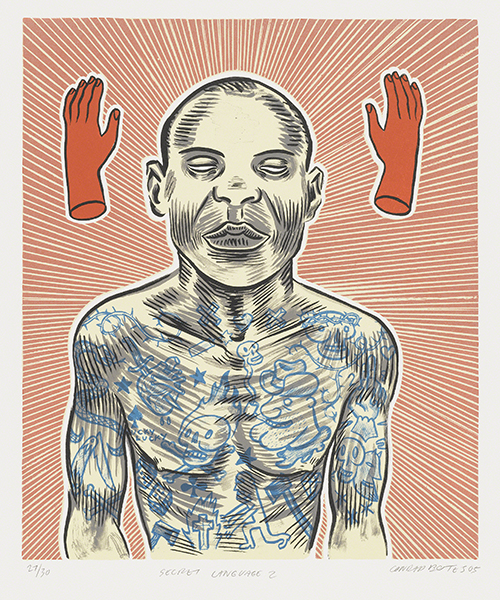

| Conrad Botes (born 1969, South Africa), Secret Language II, 2005. Color lithograph on paper, 26" x 19 ⅞" (66 x 50.5 cm). Courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2021 Conrad Botes. (MOMA-P4488) |

Secret Language II was the poster for the exhibition Impressions from South Africa, 1965 to Now (2011). It presents an African male covered in prison tattoos. The disembodied hands are one of Botes's symbols for creativity. Botes often uses isolation to amplify details of his narrative. Rather than explaining his work, he prefers viewers draw their own conclusions. This print no doubt relates to the mass imprisonment of Blacks in South Africa during the Apartheid years.

Botes' prints are characterized by a simplified contour lines, strong hatching and cross-hatching, subdued palette, and a graffiti-like sensibility. Many characters, like the one is Secret Language II, are inspired by stories Botes has produced as comics with his Bitterkomix studio. His work is representative of the strong vein of protest art that runs in the South African art world since before Apartheid was dismantled.

Born in Ladismith, Western Cape province, today Botes lives and works in Cape Town. His keen observation of all stations of South African society has given him a developed eye for targeting the myths, conceits, and delusions of Afrikaaner culture (those of Dutch heritage) and South African society in general.

The last fifty years have represented massive social and political change in South Africa. Since the end of apartheid in 1994, there has been a surge in the modes of expression, adaptation of contemporary trends, and personal narrative in Black South African art. Because of its mix of Black and European-ancestry cultures, South Africa has one of the most vital communities of contemporary art on the African continent. South African artists often juxtapose and combine elements from different cultures, races, and time periods in their art.

At the same time, South African artists explore a range of topics that reflect on their country’s past and present, including the injustice and brutality of apartheid, influence of art on politics, and daily life. Artists also examine the idea of identity, such as the cultural identity of the country and how the human body can express ideas of marginalization, prejudice, and resettlement.

Correlations to Davis Programs: A Community Connection 2E: 1.6, 6.1; A Personal Journey 2E: 4.1, 6.1, 6.6; Focus on Photography 2E: Chapter 6; Race and Art Education

Comments