It's Here -- Really: Ernest Lawson

Spring really is here, although it may not yet look like it outside (it’s actually snowing right now!). How about experiencing it on the inside with these two phenomenally beautiful little paintings by Ernest Lawson? He’s another of those artists who is not exactly a household name (even in art history households—yes, they do exist), which is unfortunate.

Like many, many, many artists, his career as an artist was not rewarded with massive riches, but his vision as an artist never failed to see the beauty around him, particularly in spring.

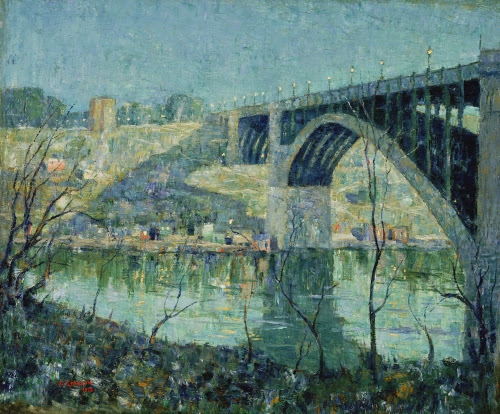

|

| Ernest Lawson (1873–1939, United States), Spring Night, Harlem River, 1913. Oil on canvas mounted on wood, 25 1/8" x 30 1/8" (63.8 x 76.5 cm). © The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC. (PC-245) |

Ernest Lawson was born in Nova Scotia. He studied painting at the Art Students League in New York, and then in the Cos Cob Art Colony in Connecticut. His mentors there were Julian Alden Weir (1852–1919) and John Henry Twachtman (1853–1902), both of whom had studied in France and developed a type of American Impressionism. Lawson, from early on, adapted the Impressionist palette, and the delicate tonalities and textures of his two mentors from Cos Cob.

From 1893 to 1896 Lawson was in France. He briefly attended the Académie Julien, where many of the impressionists had studied in the late 1860s. He met the impressionist Alfred Sisley (1839–1899), and thereafter confirmed a love of painting outdoors. When he returned to the United States, he concentrated painting scenes of Manhattan in all different weather and seasons, communicating a deep love for the city. Many of Lawson’s scenes of New York are of Harlem, then on the edge of as yet unbuilt-upon land.

This painting of the Washington Bridge between Harlem and the Bronx on 181st Street on a glistening spring night is a worthy descendant of French Impressionism. Compare it to Monet’s Railroad Bridge at Argenteuil. The composition is strikingly similar, as is the beauty of Lawson’s color harmonies and palette. Lawson’s compositions tended to emphasize strong horizontals balanced by verticals of trees, grass, and, in this painting, the vertical supports of the bridge.

|

| Claude Monet (1840–1926, France), Railroad Bridge, Argenteuil, 1874. Oil on canvas, 13 7/16" x 28 13/16" (54.3 x 73.3 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-1062) |

Lawson’s impressionist palette combined with a strong compositional sense must have seemed too progressive for the time because it did not follow the old formulas. After the rejection of a painting by the dictatorial National Academy of Design in New York in 1905, he joined the rebellion against it by joining with the group called The Eight, who are also called the Ash Can School for their unvarnished realistic scenes of New York. Lawson exhibited with them for one show in 1908. He also joined with the Independent Artists exhibition in 1910 and the Armory Show in 1913. This was really the high point of his career. He never really became a financial success as a painter. In the 1920s he briefly pursued a career in teaching.

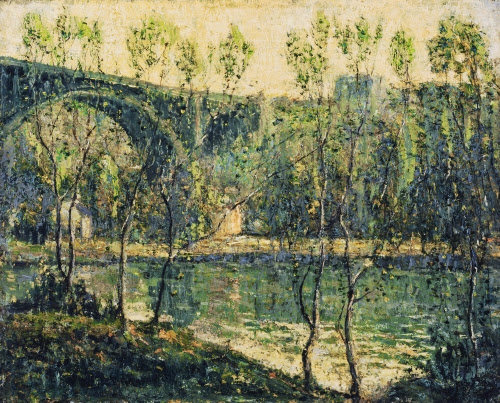

Here’s another view of the Washington Bridge from the other side, looking in the same direction:

|

| Ernest Lawson, Spring Morning, 1913. Oil on canvas mounted on cardboard, 16 1/8" x 20 1/8" (41 x 51.1 cm). © The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC. (PC-244) |

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 1: 4.connections; Explorations in Art Grade 2: 1.4; Explorations in Art Grade 3: 4.19-20 studio, 4.21; Explorations in Art Grade 4: 1.3-4 studio, 1.4; Explorations in Art Grade 5: 4.19; Explorations in Art Grade 6: 2.7; A Community Connection: 6.2, 6.4; Experience Painting: 6; Exploring Painting: 7, 11; Exploring Visual Design: 5; The Visual Experience: 9.3; Discovering Art History: 15.1, 15.activity 1

Comments