Smoke

I happen to burn a lot of incense, because I think it’s nicer than any of those spray products that immediately fall to the floor and dissipate. And who wants a plug-in air freshener that runs up the electricity bill? But I digress. Recently, I had some incense fired up and noticed this interesting layer of incense smoke in my living room.

I noticed when I walked through it, it made really interesting swirls and patterns, and I thought (long story short), that would be interesting to paint. I haven’t attempted it, yet, but here are some artists who have depicted smoke in a variety of ways.

|

| Ancient Mexico, Mayan, Male (Priest?) Burning Incense, tripod plate, ca. 500–800 CE. Painted earthenware, width: 11" (28 cm). Private Collection. Image © 2016 Davis Publications. (8S-11240) |

Incense was burned at every major ceremony throughout Mayan lands. The painted forms on Mayan ceramics are basically shapes with contour lines around them. The incense smoke is nothing like what I saw in my apartment. It’s been simplified here to a single line coming up from the censer in the dignitary’s hand.

Ceramic arts were practiced by Mesoamerican peoples starting from the time of the Olmec (ca. 1500–400 BCE). The most important objects were vases and jars meant to hold offerings in tombs and incense burners, which were also used during burial ceremonies. Like most Mesoamerican art, most objects come from grave sites. Many ceramic objects have survived from the Mayan culture because of their traditions of including ceramics in burials.

Mayan ceramics were shaped using the coil or slab method. Tripod plates were created with the coil method with the feet applied before firing. Such tripod plates were meant to hold (food) offerings for burials.

|

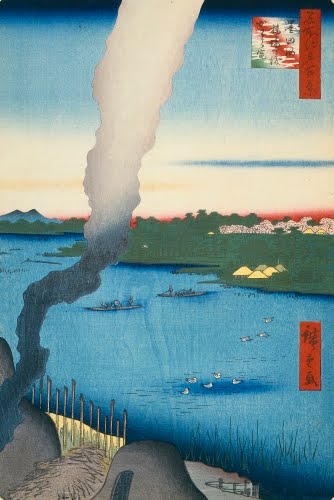

| Utagawa Hiroshige I (1797–1858, Japan), The Kilns by the Hashiba Ferry on the Sumida River, print #37 from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Color woodcut print on paper, 14 3/16" x 9 7/16" (36 x 24 cm). © Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-772) |

I’m a big fan of Hiroshige, but I seriously think that the artists who carved and printed the multiple blocks for each of his subjects deserve special admiration. I’m really liking the nuances achieved with the ink used in the smoke coming up from the kiln. The rounded kilns in the foreground are those of tile-makers in the Imado neighborhood, with pine needle piles between them for fire.

Although Hiroshige is best known in the West for his Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido (1830), he was equally renowned in his own time for One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. He published it late in life at a time when he renounced the material world to become a monk. This may account for the overall quiet tone of the subjects, where humor is only evident in details. Faces on the small figures are either hidden or nondescript, there are no merry crowds, and snow scenes have a somewhat somber air.

|

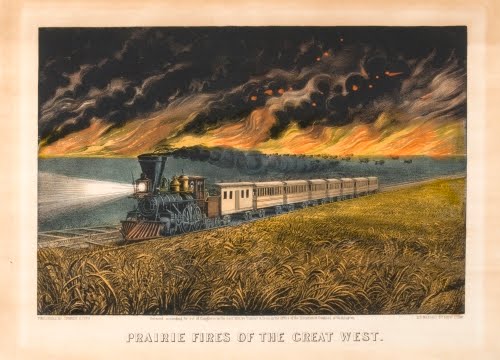

| Currier and Ives (publisher, firm 1834–1906 New York), Prairie Fires of the Great West, 1871. Hand-colored lithograph on paper, sheet 11" x 15" (27.9 x 37.9 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-4804) |

This print has double smoke action going on in it, from the train and from the prairie fire. Aside from this being an ironic juxtaposition of American technology versus our rapidly dwindling wilderness, it’s also a bit of a scary/exciting thought to be in a train watching a huge prairie blaze.

Nathaniel Currier’s firm was first called “Currier and Stodart” in 1834 (1813–1888). In1835 the firm was "N. Currier, Lithographer" which lasted until 1852, when he hired bookkeeper James Ives (1824–1895). Currier started out doing print jobs for various companies as well as architecture firms, and experimented with news events (particularly disasters), fashion prints, memorials, and portraits of prominent people. His 1840 print of the sinking of the steamer "Lexington" garnered him national attention.

Currier expanded his subjects to landscapes, genre scenes, and documentation of the US expansion in the West. That subject dominated his print output after the Civil War (1860–1865). This print comes from the last decade of the famous hand-colored lithographs, painted in watercolors mostly by a group of young women.

Although chromolithography was perfected by the time of the Civil War, Currier and Ives only issued limited edition prints in the process. After Currier retired in 1880, chromolithography took over.

|

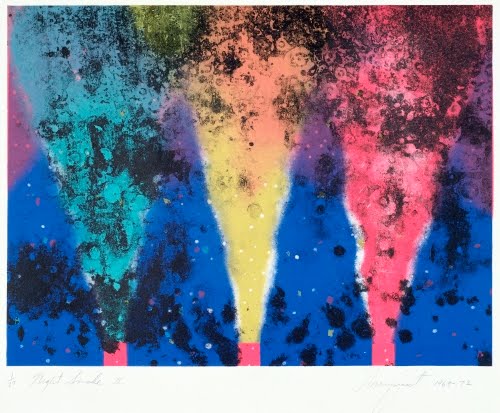

| James Rosenquist (born 1933, US), Night Smoke, 1969–1970. Color lithograph on paper, composition 16 7/16" x 21 7/8" (41.8 x 55.6 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2016 James Rosenquist / Licensed by VAGA, New York. (MOMA-P2878rovg) |

Wouldn’t you love to see multi-colored factory smoke like this instead of gray/brown smoke from American industry? This print comes from a lovely colored chalk study from the same period. Rosenquist began producing prints in order to reach a larger market with his imagery in the late 1960s.

This is a particularly fascinating work by Rosenquist compared to his needle-sharp detailed forms oddly juxtaposed with one another. The single subject is easily identified, and he has cleverly added smudges of black ink to imitate the carbon that used to rain down from factory chimneys before the Clean Air Act was passed in 1970. Although stylistically different from his well-known paintings, the subject fits right in with his fascination with the domination of American culture by the obsession with technology and “progress.”

|

| Cai Guo-Qiang (born 1957, China), Peony Postage Stamps, 2008. Lithograph and gunpowder smoke on adhesive paper, sheet of stamps 4 11/16" x 4 3/8" (11.9 x 11.1 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art. © 2016 Cai Guo-Qiang. (PMA-4237A) |

This is just a brilliant work that I include because it’s got remnants of smoke on it from gunpowder (in the form of small firecrackers) being fired. When one checks out the verso of this sheet, one can see little burn holes!

Cai's work is certainly scholarly and philosophical in the best tradition of Chinese art, but he also tries to shatter traditional conceptions of subject matter, materials, and style. He also questions traditional ideas about drawing in both East and West. Cai 's unusual choice of gunpowder and fireworks as materials for his artwork stems from his childhood in China, where fireworks historically developed.

He began experimenting with gunpowder drawings between 1986 and 1995 while staying in Japan. Many of Cai's gunpowder works are inspired by the Maoist dogma of "destroy nothing, create nothing." He produced two editions of Chinese stamps, one floral, the other of the Great Wall. He contrasts the timeless nature of the Great Wall with the momentary destruction of the gunpowder. In this work, he placed small firecrackers on the blank areas of the sheet of stamps, resulting in scorches and burns.

|

| Zoe Strauss (born 1970, US), Fireworks, Lansdowne, PA, 2009. Inkjet print on paper, 12" x 18" (30.5 x 45.9 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art. © 2016 Zoe Strauss. (PMA-7357) |

I conclude with another of my favorite artists. Strauss’s exploration of the time-honored Snapshot Aesthetic style of photography is simply brilliant. Instead of shooting the fireworks at their brightest moment, she focuses on the aftermath of their firing and dropping. Now this, of all the images for this posting, comes the closest to the incense smoke I saw in my living room! I also think it’s very nice that for years Strauss sold her Inkjet prints in a makeshift gallery under I-95 in Philadelphia for $5 each.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 6: 4.22; A Community Connection: 1.5; Experience Printmaking: 4, 6; Exploring Visual Design: 12, The Visual Experience: 10.6, 13.4, 13.5; Discovering Art History: 17.2

Comments