New Year for the Sensibilities

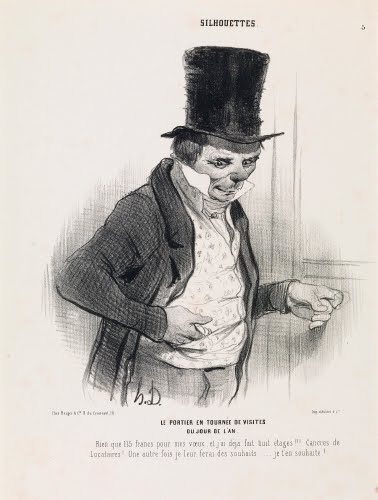

Leave it to Honoré Daumier to sum up a personality that could be any number of jerks in our current narrow-minded, materialistic, me-me-me culture. In honor of the advent of 2017, I decided to go with works of art that present unusual interpretations of the event.

|

| Honoré Daumier (1808–1879, France), The Janitor on his Round of Visits on New Year’s Day: "Just 115 francs for my good wishes and I have already done 8 floors! Miserly tenants! Next time I’ll wish them something – you can bet on it., "plate 5 from the Silhouettesseries in “La Caricature” magazine, 2nd edition, 10 January, 1841. Lithograph on paper, 13 1/4" x 10 3/8" (33.7 x 26.4 cm). © Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY. (AK-2203) |

|

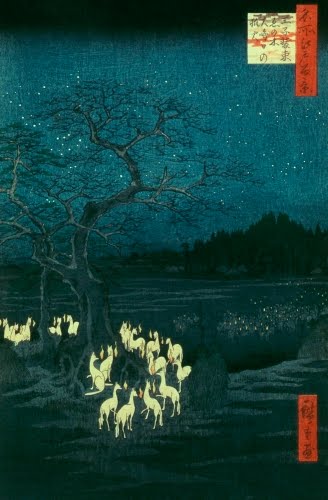

| Utagawa Hiroshige I (1797–1858 Japan), New Year’s Eve Foxfires at the Changing Tree, Oji, #118 from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Color woodcut print on paper, 13 3/8" x 8 5/8" (34 x 22 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-836) |

You might know I’d sneak a little Hiroshige in this post. Of all of Hiroshige’s prints, this is one of the most fascinating and unique in a couple of ways. This was a first for Hiroshige in choosing a mystical, rather than an observed, subject. The brilliance of its execution is a fitting end to the great One Hundred Famous Views of Edo series. The depiction of darkness is a noteworthy accomplishment by the woodblock cutters: they overprinted several different shades of gray to achieve the darkness, with touches of green overprinted on the pine and the haystacks and mica in the tree branches.

This virtuoso woodblock print depicts a New Year’s tradition about foxes congregating at the hackberry (or pine tree) near the Oji Inari Shrine. It was called “Changing Tree” because the foxes were thought to congregate there and change their “dress” to become presentable for their yearly visit to the shrine. The lights seen by farmers, either swamp gas or luminescent fungi, were ascribed to the foxes and called kitsunebi. Farmers interpreted either the shadows cast or the number of lights for crop successes in the coming year. By the way, there is still a “Changing Tree” on this spot, although the one depicted in the print died and was reverently replaced during the Meiji period (1868–1912).

|

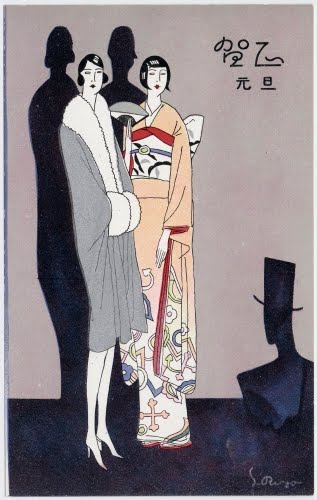

| S. Riyo (Japan), New Year’s Post Card with Silhouetted Man in Top Hat, ca. 1925–1928. Color lithograph with metallic pigment on coated card stock, 5 7/16" x 3 7/16" (13.8 x 8.8 cm). © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (MFAB-1075) |

If you’ve read my post about Nihon-ga and Yo-ga, Japanese style and Western style, you know that the Western influence in Japanese art really took off during the late Meiji era. Lithography was introduced during the 1860s. By 1873 it was a more popular medium for producing postcards than the traditional woodblock printing technique. Postcards themselves were a unique format for the Japanese, based on European examples, and made their own by Japanese artists who incorporated imagery from many traditional Japanese genres, including the Ukiyo-e prints of beautiful women (bijin-ga).

The Japanese traditionally sent surimono (New Year’s cards) with imagery and poems on them. I think this could be called an updated surimon, and an updated bijin-ga. I’m still not sure if this card is depicting an actual man standing in front of the women, or if his shadow is joining theirs on the wall. At any rate, it shows the aesthetic tension between the rapidly industrializing Japan (the “flapper”) and traditional dress (the kimono). I’m sure bobbed hair was just as revolutionary in Japan as it was in the West—women rarely cut their hair in their lifetimes in those days.

|

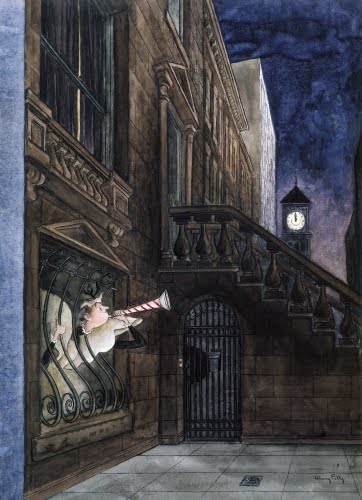

| Mary Petty (1899–1976, United States), The New Year, original cover illustration for The New Yorker magazine, published 31 December, 1949. Watercolor, ink on paper, 17" x 12 3/8" (43.2 x 31.5 cm). Image © 2016 The Museum of Modern Art, New York. (MOMA-P1770) |

This charming cover depicts the fictional maid “Fay” of the fictional, wealthy “Peabody” family on New York’s Upper East Side that were featured on numerous New Yorker covers by artist Mary Petty. By the end of the Depression (1929–1940), New Yorker covers were dominated by narrative subject matter. Unlike many of the other illustrators for the magazine, Petty avoided current events or political themes for her fictional family. Here, Fay celebrates the New Year from her prison in the basement kitchen of the family mansion. Her magazine illustration is a little more upbeat than Daumier’s, right?

Mary Petty was born in Hampton, NJ, and was more or less a self-taught artist. Already, as young person her drawings had a satiric bent to them. Her cartoonist husband, Alan Dunn (died 1974) suggested she submit her drawings to the New Yorker, and her first drawing in the magazine appeared in 1927. During her career, she produced 273 drawings and 38 ink and watercolor covers, like this one.

|

| David Gilhooly (1943–2013, United States), Going to Frog New Year’s Eve Party, 1977. Glazed ceramic, 18 1/8" x 5 7/8" x 14 3/16" (46 x 15 x 36 cm). Image courtesy of the late artist, © 2016 the artist or artist’s estate. (8S-21640) |

Gilhooly had a major thing about frogs in his ceramic sculptures, even down to frog versions of Queen Victoria. I’m not quite sure what prompted it, but in the 1970s he created his visionary “Frog World,” a parallel reality to ours in which frogs were the master species. I’m assuming here that the bear (or beaver?), moose, and bull are wearing frog masks so they can “fit in” at the New Year’s party. Like his many other animal sculptures, Gilhooly delighted in precisely rendered textures, right down to the moose fur and the birch bark of the canoe.

Gilhooly was born in Auburn, CA. At the same time that Pop Art developed in New York (late 1950s to early 1960s), the West Coast developed its own unique version that emphasized technique more than elevations of common objects. He was a member of the avant garde artists group in Davis, CA. These artists did not consider themselves “mainstream” Pop artists. Personal fantasy, often on the raunchy side, was a major component of West Coast Pop.

New Year’s Note: Curator’s Corner was greatly honored to be included in the list of “Top Twenty-Five Art Teacher Blogs” by the Feedspot website at the end of 2016. Please check out their list of the other honorees.

Comments