Native American Art "Revival": Abel Sánchez (Oqwa Pi)

When we think of “Native American art,” we tend to think of ceramics, weavings, hide objects, and quillwork. Painting (whether on canvas, paper, or wood) was not an Indian tradition until contact with whites. One of the most famous genres of Indian painting is the hide paintings of Plains cultures who documented their history after contact with whites.

Personally, I’ve always found the painting done on Pueblo ceramics to be among the most amazing and sophisticated two-dimensional examples of First Nation cultures. Pueblo and Navajo cultures also did not have a tradition of pictorial narrative, but many artists of those cultures began to experiment with narrative art in the early twentieth century. This was in part due to anthropologists and literati who realized many traditions of First Nation life were vanishing and they encouraged native artists to create art as a record.

|

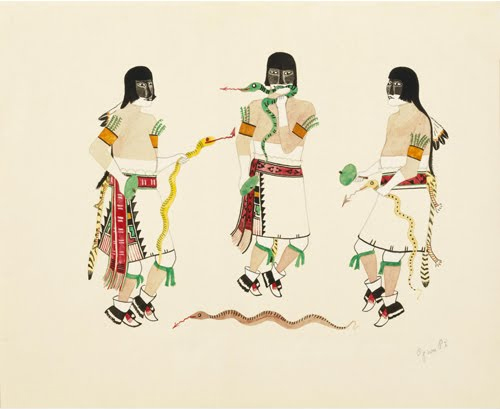

| Abel Sánchez (Oqwa Pi) (1899–1971, San Ildefonso Pueblo, NM), Snake Dance, 1920–1935. Tempera on paper, 11 ¼" x 14 3/16" (28.6 x 36 cm). Photo © Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. (MFH-814) |

The pictorial movement got its greatest impetus after the establishment of a formal art program at the Santa Fe Indian School in 1932. Non-native art teacher Dorothy Dunn (1903–1991) established the Studio, a painting program for high school-aged students. Dunn purposely did not teach western artistic ideas about perspective, plasticity, or complex composition. Instead she insisted that her students work in styles influenced by traditional Pueblo art forms such as weaving and ceramic decoration. The Studio School generated a flattened, stencil-like style that stressed subject matter. This style, known as the “Studio Style,” came to be considered “traditional Indian art” by many dealers and museums.

In the 1960s, the Studio Style was reevaluated by Native artists who considered the style a stereotype and a forced traditionalism. The Institute of American Indian Art also felt that the stylized paintings no longer adequately expressed the breadth of First Nation artistic aspiration. However, it is possible that few contemporary developments in First Nation art could have taken place without the foundation established by The Studio, which produced the first group of successful (in terms not only of sale but of wide-scale exposure) Native artists in the 1900s.

Abel Sánchez, known as Oqwa Pi (Red Cloud), was educated at the Santa Fe Indian School under Dunn. After graduation, he was commissioned to paint murals there. He returned to San Ildefonso, where he spent his life as a farmer and painter. He was very respected by the people of his pueblo and was elected governor of San Ildefonso six times. When he died, the All-Indian Pueblo Council and governors of nineteen New Mexico Pueblos signed a resolution of sorrow and presented it to his widow, Nepomucena Sánchez.

The Snake Dance, practiced by many of the Pueblos, is thought by scholars to have traditionally been a water ceremony, as snakes were considered guardians of springs. Today it is primarily held to honor ancestors and ensure adequate rain. The Pueblo First Nations consider snakes “brothers” who are able to transmit their prayers to the spirits and ancestors in the afterlife.

The Wheelright Museum of the American Indian has an exhibition running until April 2010 of painters from the Santa Fe Indian School.

Comments