National Poetry Month: Tang Yin

April is National Poetry Month in the United States. This celebration of literary pursuits was begun by the Academy of American Poets in April 1996. The celebration encourages anyone connected with books and literature, as well as schools of all levels, to promote the importance of poetry and its significance to society and culture. As an art historian, I’m naturally inclined to connect poetry to art.

|

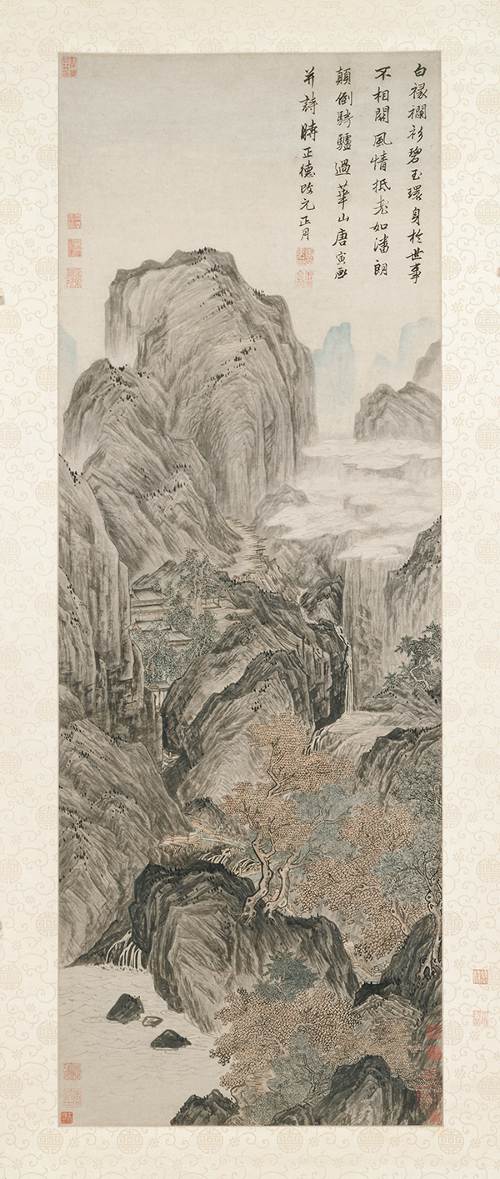

| Tang Yin (1470–1523, China), Mount Hua, 1506. Ink and color on paper, hanging scroll, 45 ⅞" x 16 ¼" (116.4 x 41.4 cm). The Cleveland Museum of Art. (8S-30074) |

Tang Yin’s paintings express feelings and emotions conjured up by his love of nature. In all of his paintings, a human presence is barely noticeable, even when his poem expresses an event. In Mount Hua, Tang pays homage to the venerable mountain, considered a Daoist holy site as the seat of the lord of the underworld. A Daoist monastery appears at the western base of the mountain. The traditional Chinese reverence for nature is taken to its highest point in Tang’s brilliant description of Mount Hua as a series of overlapping crags filled with linear detail. The craggy prominences create a zig-zag movement leading to the distant southern peak.

The poem Tang composed for this painting of Mount Hua is an ode to a scholar riding a donkey past the venerable mountain. The scholar—barely visible on the path between two prominent trees before the bridge in the foreground—is lost in reverie, unconcerned about worldly fame. It is a revealing statement by an artist who was perfectly happy being poor, if he could only commune with nature. This is indicated in the poem—perhaps a personal remembrance from a trip to Shaanxi Province—found in the upper right:

Wearing a white-bordered scholar's robe and green jade pendants, His life is unconcerned with worldly fame. Like P'an Lang resisting old age through high spirits, Crazy and clumsy he rides his donkey past Mount Hua. (Courtesy The Cleveland Museum of Art.)

|

| Tang Yin, Mount Hua, detail, 1506. Ink and color on paper, hanging scroll, 45 ⅞" x 16 ¼" (116.4 x 41.4 cm). The Cleveland Museum of Art. (8S-30074) |

Painting has been an important artistic tradition in China since the 200s BCE. In Chinese history, it has been believed that scholarship is the highest achievement and a scholar could enjoy perfection of insight into the physical and spiritual world. The reverence for the landscape combined with respect for the scholar resulted in the evolution of the scholar/artist (literati). This established a tradition in landscape painting that changed little throughout Chinese history.

Starting in the 1330s, floods and famine lasting fifteen years occurred in the Yellow River Valley. Uprisings were frequent, and in 1368 the Mongols of the Yuan dynasty (1280–1368) were overthrown by the Ming. The Ming ultimately moved the capital to Beijing to protect it from the Mongols who had fled beyond the Great Wall. The shock of Mongol rule caused the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) to look back to the artistic accomplishments of the Han (206 BCE–220 CE), Tang (618–907), and Song (960–1279) dynasties. The bitter resentment of the foreign occupation and foreigners in general caused Chinese painting to turn inward to past masters.

The son of a merchant, Tang was a painter, poet, and scholar born in Suzhou, Jiangsu province. He studied under painters Shen Zhou (1427–1509) and Wen Zhengming (1470–1559). In his quest to become a civil servant so that he could cultivate the life of a scholar/artist, Tang met failure. Instead, he decided to make a living off of his paintings as an individualist.

In an attempt to escape the disappointment of government failure, Tang lost himself in wanderings around lakes and mountains. He visited many famous peaks, including Zhurong Peak, Mount Lu, Mount Tiantai, and Mount Wuyi. In the east, he visited Dongting Lake and Poyang Lake. The splendor of the mountains inspired his paintings in which human figures are overwhelmed by the monumental grandeur of nature.

Correlations to Davis Programs: Davis Collections: Chinese Art; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 1: 1.3, 4.4, 4.5; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 2: 1.1, 1.8; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 3: 5.5, 5.6; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 4: 3.1, 3.2, 4.7; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 5: 2.3; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 6: 6.2; Experience Art: 1.3; A Community Connection 2E: 4.2, 5.1; A Global Pursuit 2E: 4.5; A Personal Journey 2E: chapter 11 pp. 154-159; The Visual Experience 4E: 8.13; Discovering Art History 4E: 4.3

Comments