National Illinois Day

Being an art historian originally from Illinois, you just know that I have to celebrate National Illinois Day with some art. I chose two fascinating artists from Chicago.

|

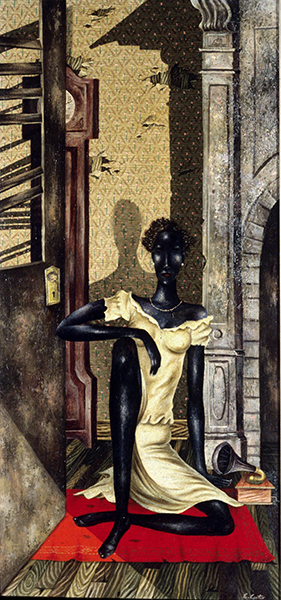

| Eldzier Cortor (1916 –2015, U.S.), Interior, ca. 1947. Oil on canvas, 41 ¾" x 22 13/16" (106 x 58 cm). Photo courtesy of the late artist and Los Angeles County Museum from the 1976 show Two Centuries of Black American Art. © 2020 Estate of Eldzier Cortor / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (8S-21934) |

In the 1940s, two grants from the Rosenwald Foundation in New York enabled Eldzier Cortor to study the Gullah community on the Sea Islands of Georgia and South Carolina. These African Americans were heavily influenced by their African heritage, which was an inspiration to Cortor. They had preserved West African language, customs, and art forms, despite slavery and the diaspora. Because of this, they became an ideal for Cortor, and Gullah women were the inspiration for an ongoing series of works embodying the African spirit symbolized by regal, attenuated images of Black women, usually singly.

Interior features a woman sitting in what was formerly an elegant American Renaissance mansion. She is regal and beautiful, although surrounded by peeling wallpaper and other signs of waning wealth. This reflects the hard realities of urban African American life. In the woman, Cortor visualized the eternity and continuity of life, and the transcendence of African American culture. The elongated form, particularly in the neck, is reflective of African sculpture, while the antique architecture reflects European artistic tradition. This represents the complicated nature of African American culture.

After World War I (1914–1918), there was a great migration of African Americans from the rural South to cities in the North. Although African American men had served in World War I, racial prejudice, segregation, and lack of opportunity in the South continued to deny African Americans the hope of fuller participation in society. Black people looked to big cities in the North in the hope of a better life.

In cities such as New York and Chicago, cohesive African American communities formed within the cities, and African Americans found a new self-awareness and pride in their heritage. During the 1920s, a significant number of artists were brought together within these large and varied African American communities, something that could not have happened in the rural South. One of the most vital African American communities was in the Harlem section of New York.

Chicago, too, had a vibrant Black artist community, mostly on the South Side. These artists banded together during the Depression (1929–1940) to form the Art Craft Guild (1932), which taught art lessons from the School of the Art Institute to many future prominent African American artists. In addition, the South Side Community Arts Center was founded around 1937, which had had backing by the Depression era Federal Arts Project.

Cortor was born in Virginia but spent his formative years on the South Side of Chicago. He began painting in high school, where his interest in politics led him to draw political cartoons. He furthered his art education at the School of the Art Institute from the mid- to late-1930s. There he was exposed to non-Western and African art. He also studied the African collection at the nearby Field Museum. He gradually formulated Afro-centric subject matter.

An exhibition of French artists from Neoclassicism to Romanticism in the mid-1940s helped Cortor formulate his mature painting style. This was combined with the influence of African sculpture he had drawn at the Field Museum and the people of the Gullah community.

|

| Charmion von Wiegand (1896–1983, U.S.), Night Intersection, 1957–1959. Oil on canvas, 24 1/8" and 24 13/16" (61.3 x 63.1 cm). Image © 2020 Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Artwork © 2020 Artist or estate of Artist. (SI-547) |

Night Intersection may represent something about Charmion von Wiegand’s mentor, Piet Mondrian (1872–1944). He reported to her that he had dreamed about a lovely composition created by crossing an intersection on the horizontal or vertical axis. This was in reference to an influence on his works such as Victory Boogie Woogie (1944). While von Wiegand emulated the structure and color emphasis of Mondrian’s work, her underlying structure was not so rigidly regulated by balance and uniformity of shapes or lines. Also, in many of her works, she went beyond the reliance on primary colors.

Born in Chicago, von Wiegand spent many years in California after the age of 12. Wandering around Chinatown there gave her a life-long interest in Chinese culture. She spent three years in Berlin as a teenager, and after returning to the U.S., studied journalism, theater, and art history at Columbia, never finishing her degree. Shortly after, intending to be a playwright, she took up painting in an Expressionist, naïve style. After 1929, she worked as a journalist and edited the New York publication Art Front. In the 1930s she counted many progressive artists among her colleagues who advised her on her painting.

When Neo-Plasticist painter Mondrian immigrated to New York in 1940, von Wiegand interviewed the artist and the two became close friends. She had known of his work, but after forming an attachment to the artist’s ideas about the reduction of artistic elements to basics, she abandoned her landscape paintings in favor of abstraction. In 1941 she joined the American Abstract Artists group, an association of artists who had bucked the dominant social realist trend of American art during the Depression. By the mid-1940s, von Wiegand’s works were obviously greatly influenced by Mondrian, but not slavishly. She subsequently experimented with collage, influenced by Kurt Schwitters (1887–1948).

From the 1950s through the 1970s, von Wiegand explored a wide range of approaches in her art, including found-object collage and many Asian themes. She was especially drawn to Egyptian, Indian, and Tibetan culture. Despite these new influences, her painting maintained a consistent content of flat, unmodulated fields of paint, a restricted palette, and insistence on geometric shapes.

Comments