Disability Awareness Month: Pearl Blauvelt

March became National Disability Awareness Month in 1987. Let’s recognize this important national observance with artist Pearl Blauvelt, whose unique vision demonstrates how enriching the work of disabled artists is to art history.

|

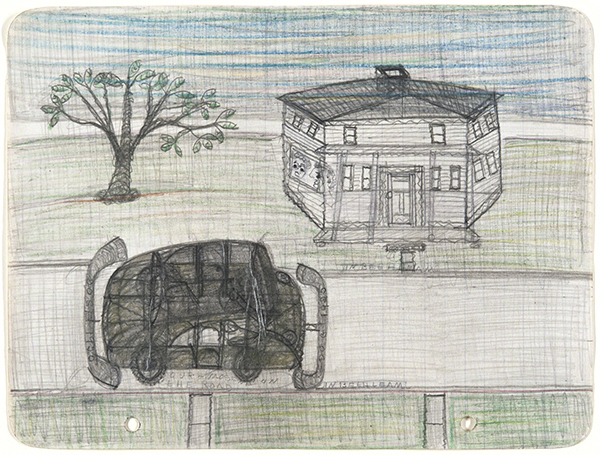

| Pearl Blauvelt (1893–1987, U.S.), House and Car, ca. 1940. Graphite and crayon on notebook paper, 7 ¾" x 10 ½" (19.7 x 26.7 cm). Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. © 2023 Artist or Estate of Artist. (PMA-8197) |

Although her works are naïve and childlike, Blauvelt strove to depict subjects accurately. Some of her works show sophisticated exaggeration or distorted scale, while in others she emphasized the plastic quality of the subject. She often inverted perspective, as seen in the house in House and Car, and rendered objects as if they were transparent, such as the car in this drawing. Blauvelt’s drawings also include everyday objects found in catalogs, which reflect a type of abstract Pop Art and epitomize the idea of appropriation as she labeled the items she copied.

There is a tradition of naïve, or “primitive,” artists that predates that of trained artists. After the 1920s, such art, often called “folk art,” gained a greater appreciation when abstraction evolved. Abstract artists came to appreciate folk art for its personal, earnest, and often intuitive vision, something for which many modernists strove. In the 2000s, the term "folk art" has been replaced by the stylistic term "Visionary Art.” Since the 1960s, museums dedicated to self-taught artists, such as the American Folk Art Museum in New York and the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore, have reshaped the thinking and understanding of American Visionary artists.

Blauvelt was a self-taught artist of Dutch ancestry whose forebearers settled in the Hudson River Valley north of New York City in the late 1600s. She moved with her father to northeastern Pennsylvania in the early 1900s, spending much of her adult life in a house without electricity or running water. Blauvelt was moved to an assisted living facility in the 1970s, where she continued drawing until her death.

Now considered an archetypal “outsider artist,” Blauvelt’s drawings reflect her limited sphere of interaction with other people, and the recollections of a woman who lived outside of mainstream society. A large body of Blauvelt’s work was found in a box in her former home. Probably created in the 1940s and 1950s, the drawings represent a wide variety of objects with which Blauvelt was familiar, such as clothing, houses, cars, and images from mail-order catalogs. She often transposed biblical references over mundane compositions. Blauvelt not only drew objects she experienced, but also things she dreamed of, the true mark of a Visionary artist.

Related Davis Publications Resources: Adaptive Art: Deconstructing Disability in the Art Classroom by Bette Naughton; Adaptive Art Resources and Webinars (free resources); Davis Collections: Artists with Disabilities (Davis Digital Images account required)

Comments