"Kalighat" Art

Indian art certainly has a rich and long history. I especially appreciate the aesthetic aspects of Indian art that have endured for centuries despite the fascinating multiplicity of kingdoms, vastly diverse religions, and numerous occupying cultures Indians have experienced.

It’s particularly interesting that new indigenous styles evolved, despite the long occupation of India by the British.

|

| India, Picture of a Woman, ca. 1800. Opaque watercolor on paper, 18 1/8" x 11" (46 x 28 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-2575) |

While large parts of India were still ruled by the Mughal Empire (1526–1756), the British ruled major parts of India through the British East India Company (a trading corporation) from 1600 to 1858. From 1858 until 1947, the British established total control—politically, economically and militarily—over almost all of present-day India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh.

The Persian influence of Mughal painting faded under British occupation, as regional schools reasserted indigenous painting styles and subjects. Major Indian cities, however, developed academies based on the stifling, conservative style of the Royal Academy in London.

Kolkata (Calcutta), in West Bengal, was the center of Britain's (economically motivated) "empire" in India. It was also a center for the Westernization of Indian art under British rule. Kolkata attracted many Bengali folk artists in search of employment, aside from those from the northern courts that gradually disbanded under the British. The reassertion of Indian folk art by rural Bengali artists, with faint touches of Western influence that started in the 1820s, has been called "Kalighat" style. This was named for the area around the Kali temple in Kolkata where many of the artists settled.

The vibrant Bengal folk art tradition adapted to the changing social conditions of colonialism in the creation of subject matter that was a combination of traditional Hindu subjects with single images of everyday life. Modifications on tradition included the use of watercolors instead of natural pigments, and the infusion of genre to reflect modern urban life. Unfortunately, modern printing techniques such as lithography, which made for cheap mass-production of images, eventually led to the waning in popularity of these works of art.

|

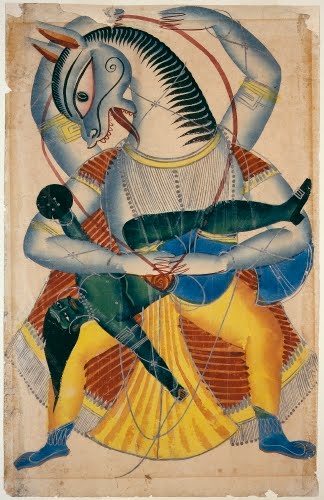

| India, Narashima, the Man-Lion Avatar of Vishnu, ca. 1910. Opaque watercolor with ink, and silver leaf on paper, 17 5/16" x 11" (44 x 28 cm). © Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-594) |

The liveliness of this depiction of the 4th avatar of the god Vishnu is typical of the energetic compositions of Kalighat artists. It shows Vishnu’s defeat of the demon tyrant Hiranyakashipu in his man-lion form. Hiranyakashipu had gained virtual immortality from Lord Brahma and used his power to persecute the devotees of Vishnu. When he sought to kill his own son Prahlad, who was devoted to Vishnu, Vishnu intervened as Narashima and saved him. This is a fairly traditional interpretation of the god’s avatar, with only hints at Western influence in the shading of the limbs to indicate volume, and, don’t miss the demon tyrant’s Western buckled shoe!

|

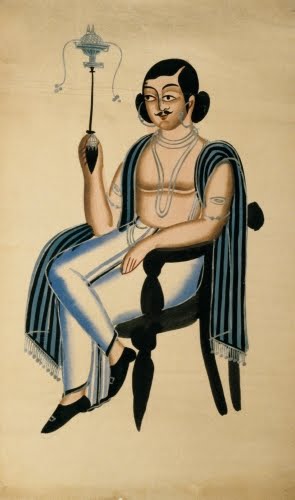

| India, Man Seated in a European Chair with a Nargila Pipe, 1880. Ink and opaque watercolor on paper, 17 15/16" x 10 3/4" (45.5 x 27.4 cm). © Cleveland Museum of Art. (CL-346) |

Did you know that the nargila pipe (hookah, huqqah) was developed either in Iran or India during the 1500s to “purify” tobacco smoke through water? Tobacco was introduced to the Safavid court in Iran during the late 1500s by Europeans, and ultimately to the Mughal court in India where smoking tobacco became popular among wealthy Indians. I’m not sure if the fact that this guy is sitting in an imported “European” chair makes him wealthy, but he is also wearing those buckled European shoes.

|

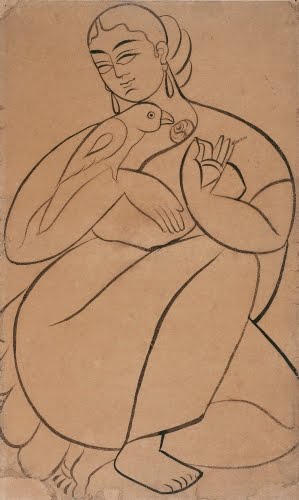

| India, Woman with a Parrot, ca. 1875. Ink on paper, 18 3/16" x 11" (46.2 x 27.9 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-3005) |

Quick sketches like this show how the Kalighat technique led to a vast simplification of form. The demand for affordable indigenous art encouraged the use of techniques that maximized output, thus the simplification of form and quick contour sketches without detail. The background was typically left unfinished for expediency's sake. Works such as this would have appealed to everyday Indians, but the style had a major influence on modern Indian art of the 1900s and to the present day.

|

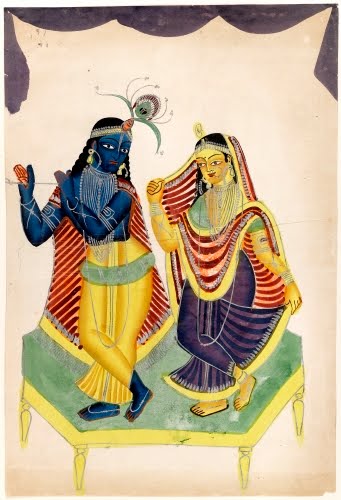

| India, Krsna and Radha, late 1800s or early 1900s. Opaque watercolor with polished accents on paper, 16" x 10 1/2" (40.6 x 26.7 cm). © Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-4513) |

The love and struggles of Radha and the god Krsna are among the most popular subjects in Indian art. Their love is so legendary, that events in their lives are chronicled in numerous texts, including the Harevamsa (“Legend of Hare Krsna”), the Gita Govinda (“Song of Krsna”), the Rasikapriya (“Connoisseur’s Delight,” a love poem about heroes and heroines), and Satasai (“Seven Hundred Love Poems”). The sloping perspective of the dais on which the god and his consort stand make this charming painting totally traditional in style.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 6: 1.4; A Community Connection: 2.2, 6.2; A Global Pursuit: 3.5; Discovering Drawing: 2; Exploring Painting: 10; Exploring Visual Design: 1; The Visual Experience: 9.2, 9.3, 13.2; Discovering Art History: 4.2

Comments