American Impressionist Watercolors: John Singer Sargent

Watercolor can be a tricky medium to master because of its transparency. Maybe that’s why I stick to oils in my personal painting. But, in the right hands, watercolors can produce amazing results.

|

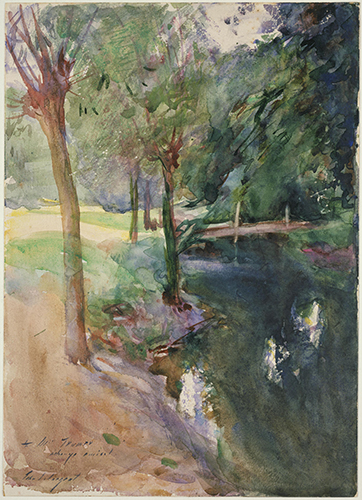

| John Singer Sargent (1856–1925, US), The Shadowed Stream, after 1900. Watercolor on paper, 13 ½" x 9 ½" (34.3 x 24.1 cm). © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (MFAB-75) |

John Singer Sargent was reared in Europe by American parents. He studied at academies in Paris where he learned traditional, conservative painting methods. His career and reputation were built on portraiture of wealthy people. Between 1885 and 1889 he was immersed in Impressionism, befriending Monet and painting outdoors with the master impressionist.

By 1900, he tired of confining himself to portraiture, and turned to landscapes with the interest of depicting light and reflected light. He had grown up sketching in watercolor, and it was his medium of choice after 1900. He traveled all over Europe, always preferring to paint outdoors with watercolor. His exhibitions in America between 1907 and his death showed a majority of watercolors to oils, which sold to major museums such as the Brooklyn Museum and Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

Like Winslow Homer and James Whistler, Sargent broke the long, stodgy green-yellow-brown tradition of watercolor by adopting the impressionist palette and relying on the white of the paper to aid in giving the effects of light and reflected light. This is clearly evident in The Shadowed Stream, where Sargent used the paper to indicate the reflection of the sky. All in all, Monet and the impressionists would have been proud of works such as this!

For great collections of Sargent’s watercolors, follow these links to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Connections Across Curriculum - The shift from hand-ground pigments to commercially available pan and tube paints in the 19th century allowed artists to paint outdoors more easily. Students can follow in these artists’ footsteps, using watercolors to create studies of their surroundings, such as geography, animals, and plants. This creative process allows for detailed study and leads to discoveries overlooked by a passing glance.

Comments