National Jewish American Heritage Month: Helen Frankenthaler

As an art historian who grew up in the age of blossoming feminist art movements, one of my major disappointments has always been the significant women artists of previous movements who were not given much exposure when they first came into their own. Helen Frankenthaler is one of them, because she was a colleague of major figures of Abstract Expressionism, Jackson Pollock (1912–1956), Willem de Kooning (1904–1997), and Robert Motherwell (1915–1991).

Frankenthaler is considered part of the “second generation” of Abstract Expressionism. Since the 1960s, of course, she established her own reputation as a pioneer American modernist, and her work no longer needs to be connected by art historians to the major figures of Abstract Expressionism, as if that movement was the do-all end-all moment in American modernism. In 1960 the poet Frank O’Hara organized the first retrospective of her work at the Jewish Museum in New York. Hence, I salute her body of work in this tribute to Jewish American Heritage Month.

|

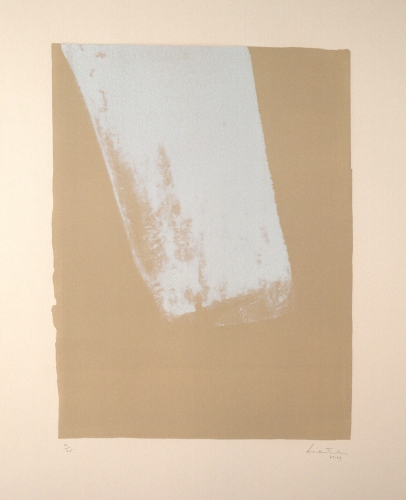

| Helen Frankenthaler (1928–2011, United States), Silent Curtain, 1967–1969. Lithograph, 30" x 22 1/2" (76.2 x 57.15 cm). Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY. © 2013 Helen Frankenthaler / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (AK-615fkars) |

Frankenthaler was born and raised in New York. She was a pupil of Hans Hofmann (1880–1966), a German Bauhaus artist who immigrated to New York and opened his own school to teach the principles of abstraction, as well as Bauhaus ideas of how to integrate fine art into design. Frankenthaler’s earliest work was influenced by Cubism. When she met Pollock, her work lost its cubist tendencies and she produced abstractions with thick paint built up. A trip to Nova Scotia in 1952 helped change her views on abstraction. She sketched landscapes in watercolor and the wash-like character of watercolor was translated to oils and acrylics on canvas. She was a pioneer of the technique of staining unprimed canvas.

Her stained canvas paintings that hinted at landscape yielded in the 1960s to works that were large, simple fields of color. While Frankenthaler’s intention may have been to depict a literal subject, her main concern was form, with spatial dynamics. The simple fields of color evolved into contrasts of positive and negative space, such as Silent Curtain. In her prints, Frankenthaler mimics the concerns of Abstract Expressionism with texture, while exploring the idea of contrasts of emptiness and shape. In a series of prints on different subjects, Frankenthaler explored mundane activity.

This piece by the artist leads one naturally to assume, values and objects are not of primary importance. What is important is contrast of positive and negative space. At this point she experimented with prints to show this contrast, often with the positive forms surrounding the blank central area. In this work, she presents the reverse. The forms are reminiscent of her stain paintings, but the subject matter, while abstract, is more recognizable.

Studio activity: An abstract everyday form. Use a piece of brown craft paper, as Frankenthaler did, and white chalk or pastel. Select a simple subject from everyday life and express it in the simplest way possible that suggests its qualities: a white window curtain, white sheets on an outside laundry line, a piece of white paper blown around in the wind, or a white flag waving in the breeze. Give it either expressive qualities or calm qualities. Either isolate the subject on the paper or create a rudimentary background using the same medium. Experiment with the white medium to create highlights that suggest sunlight surrounding the object you decide to draw.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 4: 6.35; Explorations in Art Grade 5: 6.31; Explorations in Art Grade 6: 5.25; A Community Connection: 8.2; Exploring Visual Design: 2, 6, 7; The Visual Experience: 9.4, 16.7; Discovering Art History: 17.3

Comments