Hispanic Heritage Month: Textiles of Ancient Peru

The textiles of ancient Peru—woven in every known technique for more than three thousand years—represent some of the highest artistic achievements of the cultures in that region. Textiles were the most highly prized objects after gold in Peruvian cultures, valued as a means for sharing religious beliefs. They were also worn to indicate status and authority. Peruvian textiles were made from camelid wool (probably llama, vicuna, guanaco, or alpaca) combined with various plant fibers such as cotton. The rich colors of these textiles, produced from natural dyes, likely survived due to the dry conditions of the unlit underground burial chambers in which most textiles have been found. The tradition of brightly colored, indigenous textiles continues to the present day in the country.

|

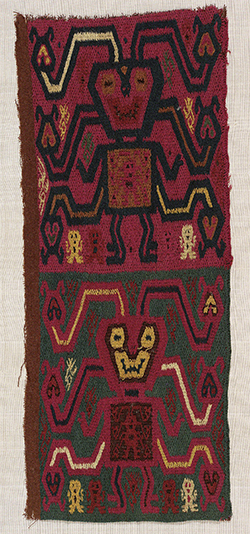

| Paracas Culture (flourished ca. 750 BCE–100 CE), Textile Border Fragment, ca. 100 BCE. Alpaca wool plain weave with stem-stitch embroidery, 13 ½" x 5 1/2” (34.3 x 14 cm). © 2023 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (MFAB-302) |

Weaving techniques in Peru became incredibly complex with some of the most elaborate being woven, unwoven, and rewoven to achieve special effects. The finest woven Paracas pieces have 200 weft (horizontal) threads per 1 square inch (2.5 cm), whereas sixty to eighty were common in European textiles. Then as now, textile artists were primarily women. The design in this piece is repeated stylized masked figures holding trophy(?) heads.

The Paracas culture was the first complex society inhabiting the southern coast of Peru. The civilization evolved over a period of some 900 years on the Paracas Peninsula, located in what today is the Paracas District of Pisco Province in the Ica Region, Peru. In the cemeteries of the Paracas culture, the dead were wrapped in multiple layers of cloth, including embroidered textiles, feathered garments, and jewelry called “mummy bundles.” Some burials contained hundreds of textiles, depending on the status of the deceased.

|

| Proto-Nazca (Curvilinear) or Paracas Necropolis (ca. 200 BCE–540 CE), Textile Fragment, 200–600 CE. Cotton and camelid fibers, 6 1/8" x 6 5/16" (15.5 x 16 cm). © 2023 Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-5455) |

The Nazca were skilled in all of the Andean textile techniques, including several types of weaving and embroidery. They also painted designs on plain cotton cloth. Abstract figures were especially popular in designs and most often are depicted participating in harvest scenes that show such foodstuffs as maize and beans. Animals, similar to those in geoglyphs and pottery designs, were also a popular subject.

This fragment bears the double fish pattern common among Nazca and Paracas textiles. The sharp teeth indicate that these probably represent sharks or killer whales. That they may represent a mythological transformation from shark to human, or vice versa, is suggested by the arms projecting from the bodies of the fish.

The predatory nature of sharks and orcas (sometimes referred to as “the master of fishes”) is made very clear in images on other textiles that portray the predator biting off the leg of a fleeing human. Human counterparts of this imagery often carry knives and heads, seemingly equating predation with human sacrifice that was so prevalent in South American cultures.

Thought to have arisen out of the Paracas culture that flourished ca. 750 BCE to 100 CE, the Nazca culture was characterized by a collection of independent chiefdoms. Although there are cultural and artistic similarities among these communities, they did not build great cities of standardized design like other Mesoamerican and South American cultures.

As the Nazca expanded their influence, they traded with inland mountain regions where alpaca and llama were raised. The also traded with rainforest regions where they secured the feathers of tropical birds for garments. The best source for Nazca art objects is from their tombs, which were often 13 to 16 feet (4 to 5 meters) deep.

|

| Wari Culture (flourished ca. 500–1000 CE), Tapestry Square Panel (probably once attached to a tunic), ca. 700–1000 CE. Camelid wool and cotton, tapestry weave, 15 1/2" x 15” (39.4 x 38.1 cm). The Cleveland Museum of Art. (8S-30054) |

The Wari produced some of the most tightly woven textiles among the Andean cultures, often containing 200 threads per inch (2.5 cm). Stylized profiles of birds of prey were privileged motifs on high-status garments such as four-cornered hats or tunics. They are also found on painted ceramic vessels used at feasts involving the consumption of corn beer and the ritual destruction of wealth. Raptors perhaps symbolized the civil and religious power of rulers, who were seen as providers of resources and mediators with the spiritual forces of nature.

Originating in the Ayacucho mountain valley in central Peru, the Wari culture developed around the same period as the Tiwanaku of Bolivia, a culture that influenced Wari art forms. The Wari culture is named after its major city. From there, Wari influence spread out over much of central and south Peru through conquest. The Wari probably had the first centralized Andean government, which became the basis of the Inca culture.

|

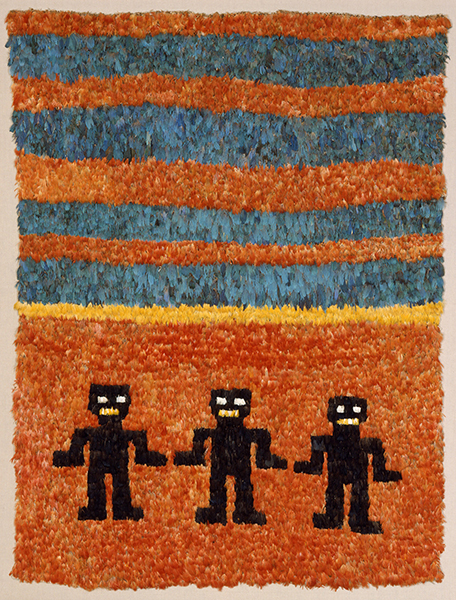

| Chimú Culture (?) (flourished ca. 900–1500), Panel, ca. 1000–1476. Plain weave cotton and feathers, 54 ¾" x 43 ¾" (139 x 111 cm). © 2023 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (MFAB-571) |

Chimú weavings such as this were usually produced in alpaca wool and cotton by male weavers. Cotton was cultivated in Peru for textiles as far back as 3000 BCE. A tabby weave is also called plain weave because it consists of only a single warp and weft. The anthropomorphic representation is that of a mythological being or deity.

Feather workers used a few coastal birds such as cormorants, egrets, ducks, and flamingos for their white, black, and pink feathers. However, the most popular feathers came from the rainforest. Macaws, parrots, parakeets, curassows, and tanagers provided the most vivid colors of yellow, green, blue, purple, and turquoise. In Chimú religion, sea birds such as pelicans were closely associated with the idea of human and agricultural fertility.

Becoming a powerful force in the region after the fall of the Wari (fell 700 CE) and Tiahuanaco (fell 1000 CE) cultures, the Chimú in turn fell to the Inca (ca. 1470). The Chimú kingdom was a highly organized society centered in the walled city of Chan Chan (near contemporary Trujillo). Tradition states that a hero called Tacaynamo landed his fleet of balsa rafts on the shore of Peru in the year 900 CE and founded the Chimú city of Chan Chan. Over the centuries, the population of Chan Chan grew to 50,000 inhabitants, as many as half of whom were artists. The artists worked in royal compounds surrounded by high adobe walls to control sand and dust. Although their ceramics were not as sophisticated as other Andean cultures, they excelled in textile production.

|

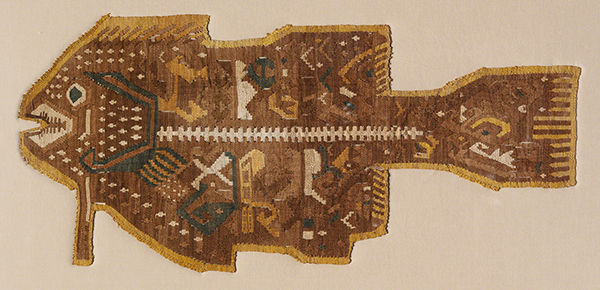

| Ychsma (Pachacamac) Culture, Fish-shaped Appliqué, 1400–1532. Cotton and camelid fibers in tapestry weave, 10" x 21 ¾" (25.4 x 55.3). The Cleveland Museum of Art. (8S-30361) |

Along with other similarly shaped appliqués, this fish form was part of a mantle that was common in Ychsma society. There are thirty-three finished edges on the piece. Such mantles have been found in tombs of Ychsma elite, wrapping mummified bodies in many layers of beautifully woven cloth and basketwork. Also found in these burials were ceramics, balls of yarn, and rope. Such textiles were also used in wrapping dead infants, many of whom had died long before their parents but were "saved" for burial until their parents died.

The fish form may represent the supreme god of fish, Wichama. He was the hero-son of the first woman created by Pacha Kamaq, the “earth-creator” who is thought to have created the earth from the sea. This legend may also account for why dried fish was often included among the food stuffs in tomb burials.

The Ychsma culture flourished along the central coast of Peru until they were absorbed by the Inca Empire in the late 1400s. Although little is known of the Ychsma, their occupation of the ceremonial site of Pachacamac is well documented. The site of Pachacamac was an important oracle center for centuries with a vast complex of monumental buildings, including at least eighteen pyramidal palaces. Although the Inca conquered the Ychsma 63 years before the Spanish invaded and conquered, they still consulted the oracle and continued ceremonial activities at the site.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art 2E Grade 3: 6.2; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 4: 5.3; Experience Art: 5.4; Discovering Art History 4E: 4.9

Comments