Hierarchical Size

Hierarchy is the level of importance allotted to an object, or, for the sake of this posting, a person. Hierarchical size deals with the principle of design known as proportion. Proportion has to do with the relationship of the size of one element of a work of art to another other. When one figure unnaturally dwarfs other figures in a work of art, it usually means that that person is more important than the others and is the center of attention, i.e. the subject matter.

|

| Ancient Egypt, Block statue of Senwosret-senebefny and Itneferuseneb, ca. 1836–1759 BCE. Quartzite, 26 7/8” x 16 3/8” x 18 1/8” (68.3 x 41.5 x 46 cm). © Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-4913) |

Egyptian women, even those in the nobility, held little power in ancient Egypt. The power the did have was centered in the home: overseeing the household and managing the household budget. Although not always the case in Egyptian funerary sculpture, wives and members of the family of the deceased are minimized in importance. Block sculptures such as this one for Senwosret-senebefny, an official in the Twelfth Dynasty (1937–1759 BCE), depict the deceased squatting on the ground covered in a cloak. The small figure is Itneferuseneb, most likely Senwosret-senebefny’s wife. Such funerary art was popular because there was a lot of surface to cover in hieroglyphics with praise for the deeds of the deceased.

|

| Ancient Egypt, Family Group, mortuary statue, ca 2371–2298 BCE. Limestone (probably painted originally), height: 29 1/8” (74 cm). © Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-548) |

This funerary commemorative portrait of a minor official, a little over two feet tall, has the minimized wife included, as well as the apple of the deceased’s eye, a male child. The pose of arms glued to the sides and one foot advancing is a convention in Egyptian sculpture that lasted through the period of Roman domination that ended in the first 500 years CE. Another convention seen through Egyptian history is the wife’s affectionate hand resting on her husband.

|

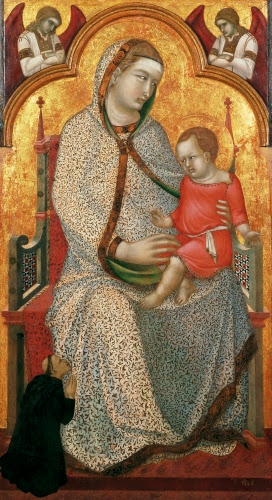

| Pietro Lorenzetti (1280–1348, Italy), Madonna and Child with Friar Donor, 1320s. Tempera and gold leaf on wood panel, 49 9/16” (126 x 76 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-448) |

Lorenzetti and his brother Ambrogio, who were from Siena, were instrumental in bringing Italian art into the beginnings of the Renaissance with their insistence on realism, monumentality, and plasticity. However, some older elements of Gothic art remain: the shallow, shrine like space, the use of gold leaf, and the miniature monk donor kneeling at the feet of the object of veneration, the Madonna and Child. During the Renaissance, donors such as this monk would have been depicted the same size as the religious figures. This was all part of the Renaissance emphasis on the individual and their accomplishments.

|

| India, Zumurrud Shah Reaches the Foot of a Huge Mountain and is Joined by Ra’im and Yaqut, page from a dispersed Hamzanama (Book of Hamza), 1557–1572. Opaque watercolor and gold leaf on cotton cloth, 26 ¾” x 20” (68 x 51 cm). © Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-646) |

The Hamzanama was a recounting of the adventures of Amir Hamza. It is an Indo-Iranian tale much akin to the adventures of Odysseus in Homer’s Illiad and Odyssey. This scene certainly rivals the Egyptian examples of minimization in the size of the followers of Zumurrud Shah, the central character in red tunic. Male figures are only slightly larger than female and child figures. Another interesting aspect of this illustration is space. Recession into the background is achieved with vertical perspective. In other words, various elements of the setting are piled one atop the other to achieve the illusion of depth.

|

| Bolivia, Madonna and Child with Saint Dominic, Saint Francis, and Indian Donors, 1700s. Oil on wood panel, 14 3/16” x 10 1/4” (36 x 26 cm). © Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-922) |

This work, done in a style derivative of the Spanish Baroque, was most likely executed by native artists. Spanish artists who migrated to the Spanish colonies in Central and South America taught native artists oil painting. Like-sized saints, as well as mini-donors accompany the Madonna and Child, the focus of veneration. The painting is interesting in that a wealthy native family who had converted to Christianity commissioned it. Compared to Spanish painting of the time in Europe, it has more of a folk-art aesthetic.

|

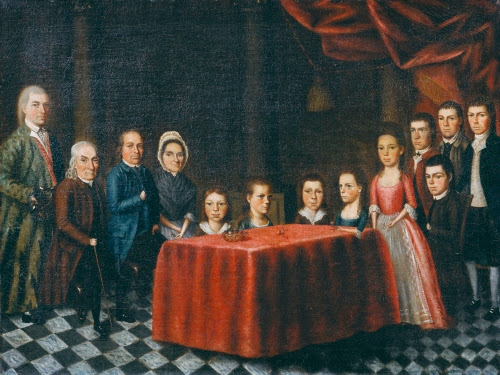

| Edward Savage (1761–1817, US), The Savage Family, ca. 1779. Oil on canvas, 26” x 34 5/8” (66 x 88 cm). © Worcester Art Museum. (WAM-104) |

The painter, Edward Savage, appears on the far left of this painting, and is practically the only figure represented in what approaches accurate body proportions. The rest of the family has huge heads on spindly little bodies. Although Savage studied painting under expatriate American painters in England, his early style reveals a self-taught quality, especially in the lack of understanding of anatomy and perspective (look at the floor tiles!). However, I still find this piece charming, especially the way the family members are arranged by height, drawing attention to the velvet-covered table in the center of the room (why?).

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 3: 1.3, Explorations in Art Grade 4: 1.2, Explorations in Art Grade 6: 1.1, The Visual Experience: 8.9

Comments