African American History Month: Henry Taylor and Carmen Cartiness Johnson

One of the avenues of expression in the flourishing of African American art since the Harlem Renaissance (ca. 1920s–1940) has been the exploration of subject matter concerning the contemporary Black American experience. Many of the artists of the Harlem Renaissance believed that it was important for them to document the struggles and triumphs of their community. Perhaps because of the power of the Harlem Renaissance movement, the exploration of contemporary Black life has become more dynamic than ever.

|

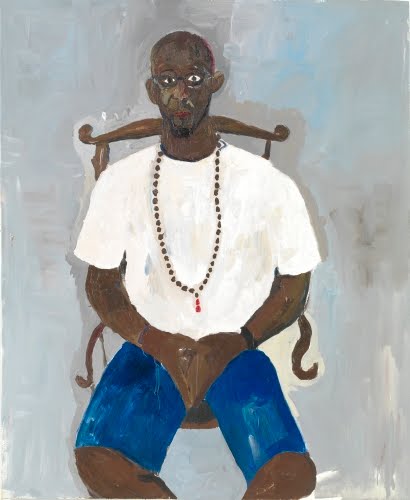

| Henry Taylor (born 1958, United States), Untitled, 2011. Synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 78" x 62" (198.1 x 157.5 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2018 Henry Taylor. (MOMA-P5082) |

The work of Henry Taylor (born 1958), particularly his portraits, are evidence that there is no disconnect between art and life. He paints scenes of everyday life (genre) and current events, but portraiture seems to be his forte. His subjects include friends, people off the street, folks from the art world, relatives, and even sports figures. He renders them in expressionistic brush work that is reminiscent of the work of Alice Neel (1900–1984). His works are, dare I say it, a form of social realism that has great sincerity, dignity, and monumentality that transcends the work of many artists designated under that style.

Taylor’s portraits are roughly painted, often reflecting the world of the artist’s experience. However, the people are depicted with a spirit of affection rather than detachment or judgement. His portraits of everyday African Americans reflect the same spirit as artists like Bob Thompson (1937–1966) or Robert Colescott (1925–2009).

Taylor was born in Oxnard, California, the youngest of eight children. While working at a state hospital as a nurse (1984–1994), he began taking art classes at the California Institute of Arts at age thirty-one. Major influences on his work are the Art Brut of Jean Dubuffet (1901–1985), the slashing figures of Abstract Expressionist Willem de Kooning (1904–1997), and German Expressionist Max Beckmann (1884–1950).

Transcending all of his art training experiences was his own childhood. His parents had lived through the Great Depression (1929–1939) in Texas. He lost a brother in Vietnam. Through all of his experiences, Taylor always remembers his father’s advice to treasure every moment for what one can learn, because of the transience of life.

|

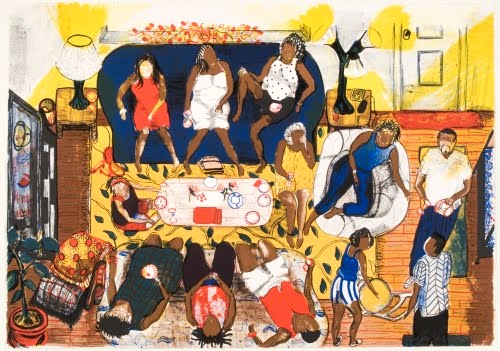

| Carmen Cartiness Johnson (born 1954, United States), To Get Together, 2005. Color lithograph on paper, 19 ¼" x 27" (48.9 x 68.6 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art. © 2018 Carmen Cartiness Johnson. (PMA-4171) |

Carmen Cartiness Johnson (born 1954) describes herself as a self-taught artist and storyteller. Indeed, storytelling is a big part of her body of work. Her passion for painting comes from her wish to visually (and joyfully) share personal narratives from her past, as well as from the people close to her. She does so in the simple, brilliant palette influenced by the work of Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), employing forms that are composed of simplified color shapes. She also references Lawrence’s tendency to depict scenes from unusual vantage points. This painting would make one swear they were dangling from the ceiling fan!

While works such as this may suggest the simplicity of color shapes in the work of Lawrence, there is a complexity of composition (the birds-eye view) visible in the painting-collages of Romare Bearden (1911–1988), another of her stated influences. The artist also admires the political content and color of Diego Rivera (1886–1957).

Born and raised in Kansas City, Missouri, Johnson now lives and paints in New Jersey. She began teaching herself to paint after her grandmother died. Her earliest works were emotional memories of spending summers with her grandparents in Arkansas. Connecting to intimate circumstances and transmitting feelings of warmth and affection are a main goal of Johnson’s art. She also gets subjects from the words in songs, poems, novels, and movies. Ultimately, she wants viewers of her work to be able to relate to what she has depicted. In the grand scheme of things, Johnson’s work embraces the whole range of human experience from joys to sorrows.

View the other posts in my African American [Art] History Month 2018 series.

Comments