Gem of the Month: Kyoko Tokumaru

Kyoko Tokumaru is a brilliant sculptor who creates organic forms in ceramics, fashioning complex pieces out of hard-to-work-with porcelain. Like many contemporary clay sculptures, Tokumaru’s works defy the fired hardness of the material, imitating naturally growing elements either underground or waving in the breeze. The beauty of her works has earned her my Curator’s Corner Gem of the Month selection for June 2024.

|

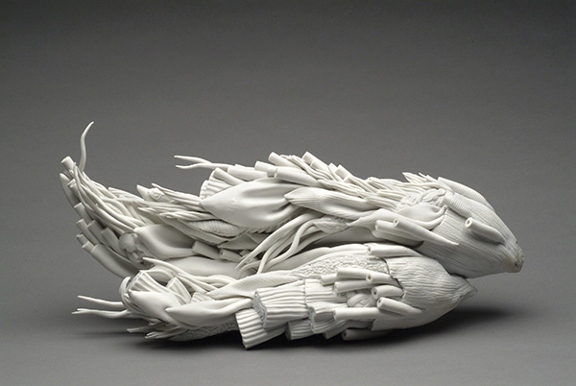

| Tokumaru Kyoko (born 1963, Japan), Germination, from the ongoing series Cosmic Plants, 2001. Earthenware, 9" x 21" (22.9 x 53.3 cm). Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. © 2024 Tokumaru Kyoko. (PMA-9545) |

Tokumaru has created numerous iterations on the subject of Germinations—the growth of a seed into a seedling—in her organic sculptural forms. This work explores the concept of growth with references to roots, a trunk, and branches. These are symbols of the universal, cosmic tree, the three parts representing the underworld, earth, and sky. Part of her Cosmic Plants series, this work is based on the form of a rhizome, a horizontal stem that grows underground and sends out shoots and roots. Tokumaru’s work is grounded in the traditional coiling method. Many of the forms in Germination are also based on molds made from found objects such as plastic tubes and pieces of discarded materials, all meticulously assembled into a whole that is both natural and otherworldly.

During the Jomon Period in Japan (ca. 3000–200 BCE), artists produced some of the oldest known utilitarian ceramic forms with aesthetic, rather than functional, decorations. Traditionally, ceramic arts in Japan are considered fine art, much in contrast to the Western perception of “decorative arts.” The development of the tea ceremony in Japan during the Muromachi Period (1392–1573), including the important component of flower arranging, cemented the long-held place of honor ceramics has in Japanese art.

In the early 1900s, a group of ceramic artists in Japan, inspired by the British Arts and Crafts Movement, founded the Japanese Folk Art Association. They were also reacting against the rapid Westernization and industrialization of Japan. The group fostered the idea of the studio ceramic artist, one who actively participates in every aspect of ceramic making. The need to restore a national identity after the disaster of World War II (1939–1945) helped strengthen the movement to fortify traditional art forms. At the same time, many younger Japanese artists, rejecting the strictures of traditional Japanese art forms, sought inspiration from Western art as Japan quickly became part of the modern world.

In the late 1940s and 1950s, counterparts in the United States also looked to change the perception of ceramics from a utilitarian art to fine art. American artist Peter Voulkos (1924–2002), a West Coast ceramic artist with links to avant-garde art movements and Abstract Expressionism, moved away from functional ceramics to create large clay sculptures. Like Voulkos, the pioneering modern ceramic artist Kazuo Yagi (1918–1979) used traditional Japanese ceramic forms and the traditional respect for the medium as a jumping-off point to introduce uniquely modern ceramic art.

Combining traditional coiling processes and found objects, the abstract forms of Tokumaru’s sculptures uphold ceramics as a contemporary art form. Born in Tokyo, Tokumaru earned her BFA in ceramics in 1990 and MFA in ceramics in 1992 from Tama University. The undulating, twisting forms of Tokumaru's sculptures impart a weightless, almost floating underwater look to her works, defying the brittle, hard quality of high-fired porcelain or earthenware. She says that a major influence on her forms are the floral offerings and decorations found in Japanese temples, which she equates with the prayers and magic inherent in the human race.

Correlations to Davis programs: Experience Clay 3E: p. 40, 292; The Visual Experience 4E: 5.6, 10.5, 10.13

Comments