Northern Renaissance Engraver: Israhel van Meckenem

I like showing you works from the Renaissance period in Northern Europe. This is partly because my mother was Swiss and I wrote my master’s thesis about a Swiss Renaissance painter (yes, Switzerland, too, had a Renaissance period), and partly because northern artists emphasized often extreme realism as opposed to the blah-blah-blah perfection of antique classicism in Italian Renaissance art.

Printmaking was an important medium during the Renaissance in the north, so much so that prints were collected in the same way paintings were. Some of the earliest museums established during the late 1500s, as I’ve mentioned, were collections of graphic arts, and not simply copies of paintings. Nowhere was printmaking a more revered and highly developed art form than in Germany.

|

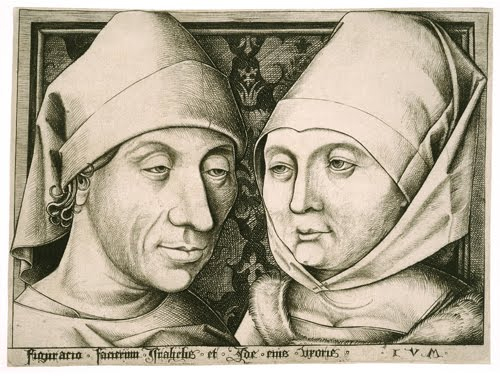

| Israhel van Meckenem (1440/1445–1503, Germany), Self-Portrait with His Wife Ida, ca. 1490. Engraving, 5 1/8" x 7 1/16" (13 x 18 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-2756) |

Engraving is an example of intaglio printing, which is a technique that has endured in popularity through to the present day. Intaglio printing is the opposite of relief printing. The image is cut or incised into a metal plate with various tools or acid. The wide variety of methods gives the medium a large range of possibilities of expression. Engraving was the first intaglio process to emerge, most likely from goldsmiths’ practice of incising designs on metal and then inking those designs, pressing them on paper for later reference. Scholars believe this happened in southern Germany in the 1430s.

In engraving, the image is incised onto the finely ground metal plate (most often copper) with very sharp tools such as needles, burnishers, and scrapers. An acid bath then eats into the incised lines from which the print will be pulled, after which ink is rolled across the plate, filling in the incised lines. The plate is then wiped clean, leaving ink only in the crevices. A sheet of damp paper is placed on the plate and the plate is run through a press which forces the paper into the inked crevices and transfers the image.

Israhel van Meckenem was a very prolific printmaker. Son of a goldsmith-printmaker, he produced more than 600 prints, although only about a quarter are original compositions. It was common during this period to appropriate the compositions of other masters.

This print, however, is an original—the first engraved portrait in the history of printmaking. Typical of Northern European realism, he does not idealize his features or those of his wife/business partner. Engraving was a favorite medium for northern printmakers, because of the detailed nuances in shading possible with the sharp tools used to scratch out the image. This print is an excellent example of the use of crosshatching to create plasticity of the figures.

Comments